May 24, 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of Molly Lamb Bobak’s appointment as Canada’s first female war artist during the Second World War.

In 1942, Molly Lamb Bobak was fresh out of art school in Vancouver. The talented young painter promptly joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) as a draughtswoman—dreaming of one day becoming an official war artist. She worked serving in canteens before being sent on basic training in Alberta, eventually being promoted in 1945 to Lieutenant in the Canadian Army Historical Section.

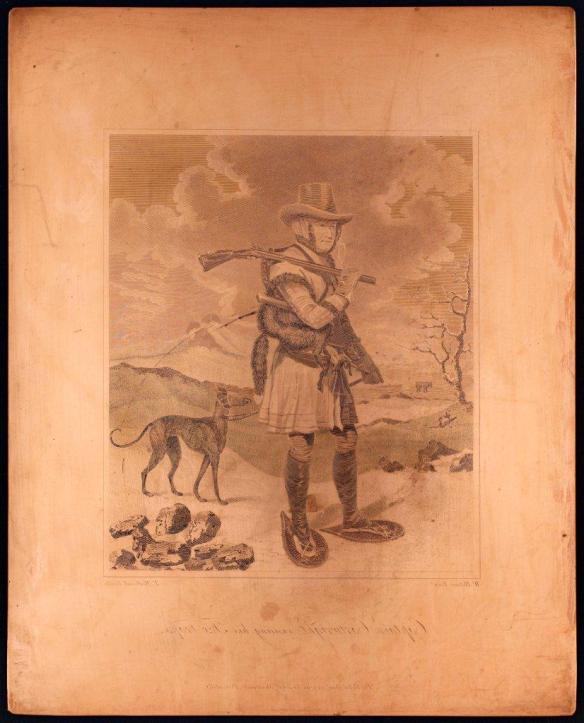

War artist Lieutenant Molly Lamb, Canadian Women’s Army Corps, sketching at Volendam, Netherlands, September 1945 (MIKAN 3217951)

Shortly after enlisting, Lamb Bobak began writing a unique diary that provides an invaluable record of the CWAC’s role in the war effort. Titled simply W110278, after her service number, it is a personal and insightful, handwritten account of the everyday events of army life, accompanied by her drawings. Dating from November 1942 to June 1945, the diary contains 147 folios and almost 50 single sheet sketches that are found interleaved among its pages.

The diary’s first page captures the humorous tone and unique approach of the diary. Written as a pseudo newspaper, with the pages resembling big-city broadsheets, the first headline reads “Girl Takes Drastic Step! ‘You’re in the Army now’ as medical test okayed.”

What follows are handwritten news bulletins with amusing anecdotes and vibrant illustrations that reveal women’s experiences in Second World War army life and form part of a personal daily record of Lamb Bobak’s time in the CWAC.

Three years after enlisting, Moly Lamb Bobak achieved her ultimate goal when she was appointed as Canada’s first female official war artist and was sent overseas, after the ceasefire, where she painted in England, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.

To celebrate the 70th anniversary of Molly Lamb Bobak’s appointment as the country’s first female official war artist, Library and Archives has digitized her entire Second World War diary in colour, making this national treasure available online.

Related resources

- View W110278, Molly Lamb Bobak’s war diary

- Watch the Molly Lamb Bobak: Canada’s First Female Official War Artist – three-part interview with Molly Lamb Bobak

- Explore the Molly Lamb Bobak and Bruno Bobak fonds

- Visit the travelling exhibition The Artist Herself: Self-Portraits by Canadian Historical Women Artists, at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston from May 2 to August 9, 2015, to view a few pages from Molly Lamb Bobak’s diary