The Discover Blog returns to the First World War Centenary: Honouring Canada’s Victoria Cross recipients series, in which we profile each of Canada’s Victoria Cross recipients on the 100th anniversary of the day that the actions for which they were awarded the Victoria Cross took place. Today we present the story of Lieutenant Frederick Maurice Watson Harvey, an Irish-born Canadian VC recipient from Medicine Hat, Alberta.

Captain Frederick M. Harvey, V.C., undated (MIKAN 3216613)

Harvey, born in Athboy, County Meath, Ireland, was one of three Irish rugby union internationals to have been awarded the Victoria Cross, and the only one to have been awarded the medal during the First World War. He settled in Medicine Hat, Alberta, in 1908 and enlisted on May 18, 1916 with the 13th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles, transferring to Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) after arriving in France.

On March 27, 1917, Harvey’s troops advanced on the village of Guyencourt, France. As German machine gun fire inflicted heavy casualties, Harvey’s Victoria Cross citation recounts what occurred next:

At this critical moment, when the enemy showed no intention whatever of retiring and fire was still intense, Lt. Harvey, who was in command of the leading troop, ran forward well ahead of his men and dashed at the trench, still fully manned, jumped the wire, shot the machine gunner and captured the gun. His most courageous act undoubtedly had a decisive effect on the success of the operation (London Gazette, no.30122, June 8, 1917).

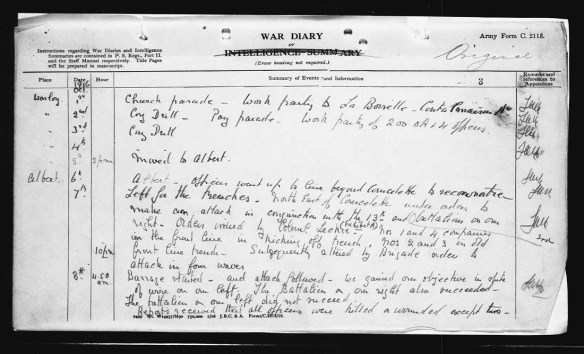

Extract from the Lord Strathcona’s Horse war diaries for March 27, 1917 (MIKAN 2004721)

Lieutenant Harvey was initially granted the Distinguished Service Order but was later awarded the Victoria Cross. He received the Military Cross for his role in the Lord Strathcona’s Horse advance on Moreuil Wood on March 30, 1918 and was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre.

Harvey remained with Lord Strathcona’s Horse and was promoted to Captain in 1923. He instructed in physical training at the Royal Military College of Canada from 1923 to 1927, was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1938, and, in 1939, was made Brigadier General. Harvey served as Honorary Colonel in Lord Strathcona’s Horse from 1958 to 1966. He died in August 1980 at age 91.

H.M. The King decorating Lieutenant Harvey L.S.H. with the Victoria Cross (MIKAN 3362384)

Library and Archives Canada holds the CEF service file for Lieutenant Frederick Maurice Watson Harvey.