This Black History Month, Library and Archives Canada highlights the service of Black Canadians during the First World War. While all Canadians were equally caught up in the patriotism of the early part of the war and the opportunities offered by military service, Black Canadians had difficulty enlisting due to the racism of the era. Although there was no official or explicitly stated policy of exclusion, the Canadian military left recruitment decisions to the discretion of individual commanding officers. Black Canadian volunteers along with those from other minority groups were left to enlist in whichever regiments would accept them. A special unit, the No. 2 Construction Battalion, was formed by members of the Black community in Nova Scotia. The battalion, whose members weren’t allowed to fight, dug trenches, repaired roads, and attracted hundreds of recruits from across Canada and even the United States.

Jeremiah “Jerry” Jones, First World War private taken by an unknown photographer, from the personal collection of the Jones family (Wikipedia).

Among those Black Canadians who volunteered and served was Jeremiah “Jerry” Jones, a Nova Scotian soldier who enlisted with the 106th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles) in June 1916. Born in East Mountain, Nova Scotia on March 30, 1858, Jones was over 50 years old when he enlisted and lied about his age in order to join the army. Jones was sent overseas, where he transferred to the Royal Canadian Regiment and saw combat on the front lines in France, including the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. During the battle, with his unit pinned down by machine gun fire, Jones moved forward alone to attack the German gun emplacement. He reached the machine gun nest and threw a grenade that killed several German soldiers. The survivors surrendered to Jones, who had them carry the machine gun back to the Canadian lines and present it to his commanding officer. It is reported that Jones was recommended for a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions, though no record exists to show that he ever received the medal. In the decades following the war, the Truro Daily News and Senator Calvin Ruck highlighted Jones’ bravery and lobbied to have the Canadian government formally recognize his actions. Ruck in particular argued that the racist sentiment of the time had prevented Jones and other Black soldiers from being properly recognized for their heroism.

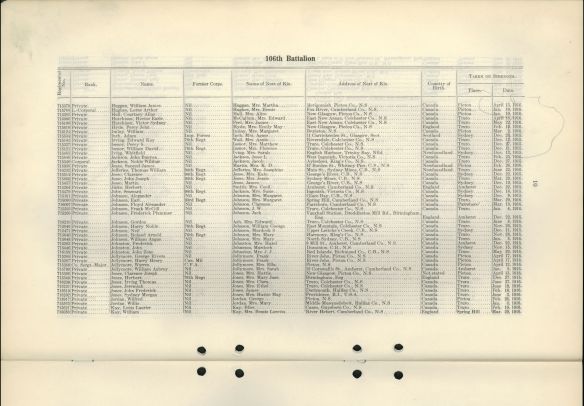

Entry for Jeremiah Jones in the “Nominal Roll of Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and Men” of the 106th Battalion (e011092698).

Jones was injured at the Battle of Vimy Ridge. He was formally discharged in Halifax in early 1918 after being found medically unfit. He died in November 1950. Jeremiah Jones was posthumously awarded the Canadian Forces Medallion for Distinguished Service on February 22, 2010.