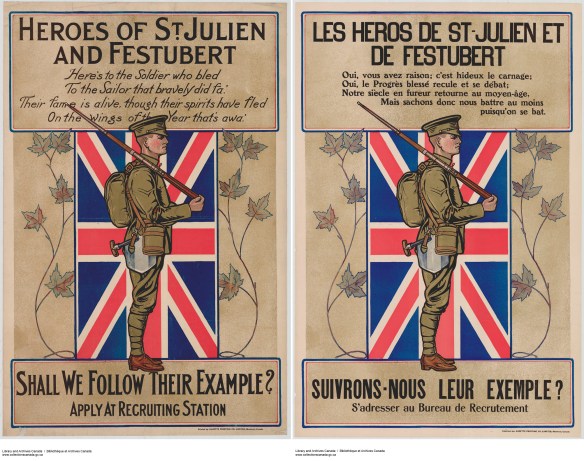

The incredible contribution of Canadian nursing sisters in the First World War can be best appreciated by examining their experiences during service. Women left their families and homes to answer the call to duty and serve their country. Their dedication to their work, to Canada and, most importantly, to their patients, serves to measure the profound effect they had on the Canadian war effort.

An unidentified nursing sister (MIKAN 3523169)

Library and Archives Canada holds a variety of materials on the history of military nurses, both published and archival. Below you will find a few examples:

A closer look at their daily lives

There are several recent publications that shed light on the varied experiences of nursing sisters during the Great War. Some focus on the individual accounts of nurses:

- Debbie Marshall’s Give Your Other Vote to the Sister: A Woman’s Journey into the Great War

- Shawna M. Quinn’s Agnes Warner and the Nursing Sisters of the Great War

- Harry B. Barrett’s Port Dover’s Nursing Sisters of World War I: Memories of Minnie and Laurel Misner

- Sherrell Branton Leetooze’s WWI Nursing Sisters of Old Durham County: the stories of 36 brave women who, despite the dangers of war, stepped into unknown territory to apply their skills

Pat Staton’s It Was Their War Too: Canadian Women and World War I offers a more general perspective of their contribution to the war effort.

Two nursing sisters with wounded soldiers in a ward room at the Queen’s Canadian Military Hospital in Shorncliffe, Kent, England, ca. 1916 (MIKAN 3604423)

In the archival collection, we are lucky to have the complete fonds for six of these nursing sisters, which allows us to delve deeper into what it was like for these women in the field. Learn more about Sophie Hoerner and Alice Isaacson who both served in France, or Dorothy Cotton who served in Russia. If that is not enough, you can learn about Anne E. Ross, Laura Gamble and Ruby Peterkin who all served in Greece.

Looking for a specific nursing sister?

If you are looking for information about a nursing sister who served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, you will likely find it in the database Soldiers of the First World War. Generally, nursing sisters can easily be identified by their rank, usually indicated by “NS”. It is also important to note that that many women served with the British Forces through the Victorian Order of Nurses or St. John Ambulance.