By Anik Laflèche

If your last name is Schneider, Sigman, Henry, or André, or it has “von” in it, you may be of German descent.

In 1776, the Thirteen Colonies declared the United States of America to be independent from Great Britain. Many reasons were behind this declaration, including excessive taxation and lack of representation in Parliament. Civil war broke out in central North America, pitting George Washington against Benedict Arnold, and John Adams against Samuel Adams. This brutal civil war finally ended in 1783 when Great Britain accepted the independence of its old colonies. The United States would become a country and Great Britain would keep the northern colonies, now Canada. This started a massive wave of migration (almost 70,000 people including British citizens, First Nations and freed enslaved people) to what are now the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

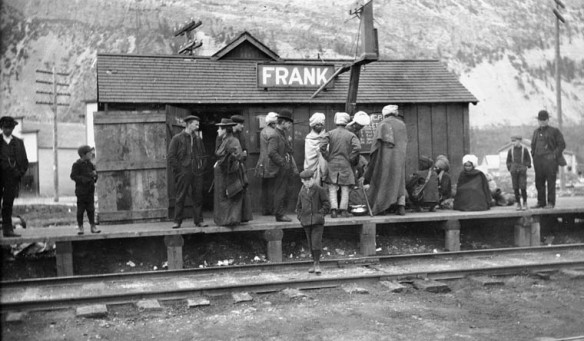

United Empire Loyalists Landing at the Site of the Present City of Saint John, New Brunswick, 1783 by John David Kelly, reproduced in Confederation Life’s 1935 calendar (e011154201)

While numerous families arrived during this massive wave of settlement, many Canadians are descendants of a smaller, less noticeable population migration that happened simultaneously—not First Nations, French, American or English immigrants, but surprisingly—German mercenaries, also known as Hessians.

Let us backtrack a bit in our story of American rebels and British Loyalists. From the late 1770s to the early 1780s, King George III of England, faced with war in the colonies, decided to hire 30,000 German soldiers (that is a German soldier for every 22 Québécois!) and ship them to the New World to combat the rebellious states. While many of these mercenary regiments were sent directly to the Thirteen Colonies to fight, some were deployed in Canada to protect the frontier, such as the Hesse-Hanau Regiment, which were active in the forts of Ontario and Quebec.

Transcription of a War Office letter from officer de Looz concerning the movement of the Lossberg regiment, 1783. (MG13 WO28, vol. 8, p. 224, microfilm C-10861)

Although the German mercenaries and Loyalists fought valiantly, the balance of power tipped in favour of the American patriots. After the war was over, the German mercenaries were offered a choice of returning home to Germany or settling in Canada. Many soldiers decided to stay in Canada, settling in Lower Canada, Upper Canada, and Nova Scotia—learning French or English, marrying local girls, and assimilating into the surrounding societies.

But how did so many Canadian families forget their German ancestors? Should it not be easy to pinpoint a German name in our family trees? Not necessarily as in the 18th and 19th centuries, spelling of names often changed throughout people’s lives. Spelling, especially when foreign words were concerned, was based on sounds, and thus varied greatly. In the case of the mercenaries, local French or English priests were the ones recording names for marriages, births and deaths. When they heard a German name, they often francized or anglicized them based on what they understood. Thus, Heinrich Kristof Sieckmann, a German mercenary born in Vlotho, Germany, who served in the Hesse-Kassel Regiment, became Henry Christopher Sigman and André Christophe Sicman. A few generations later and other phonetically similar variations started to appear such as Ciegman, Sicman, Sickman, Sigman, Sickamen, Silchman and even Tieckman. With this new spelling, Heinrich Sieckmann, now Henry Sigman, could easily have been mistaken for an English immigrant on paper.

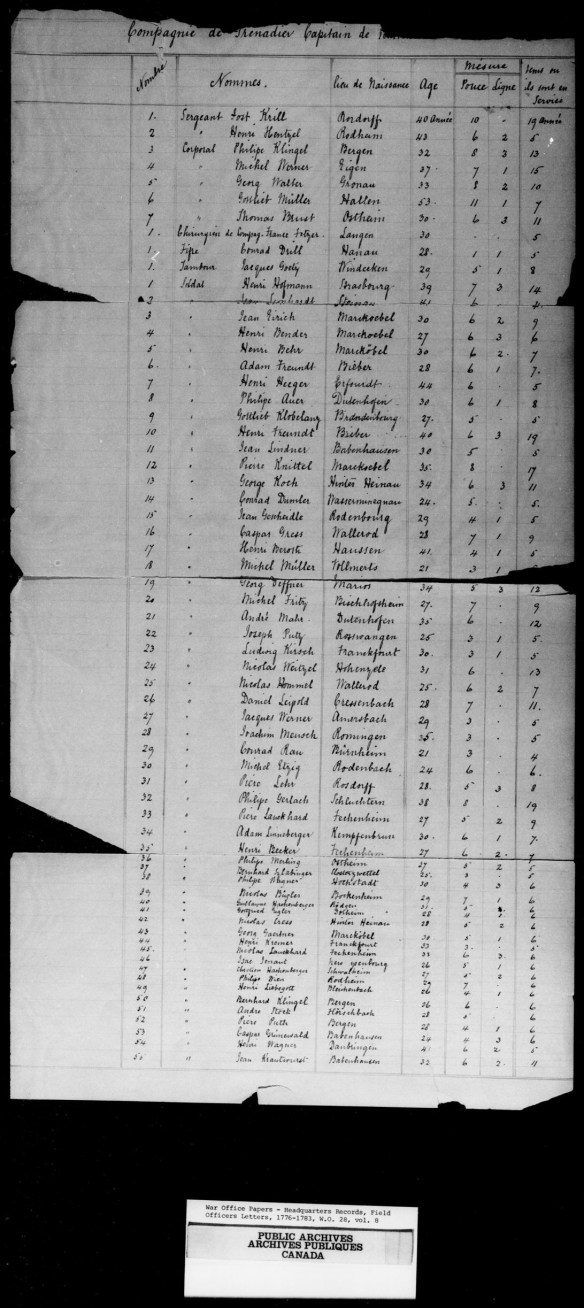

War Office 28: nominal roll of the 1st Hesse-Hanau Battalion, January 1783 (MG13 WO28, vol. 8, p.205, microfilm C-10861)

So to the Henrys and Andrés (Heinrich), the Sigmans (Sieckmann) and the Schneiders—if this might be you or if you are simply curious to learn more about these German soldiers that popped up on the Netflix show Turn, come on over to Library and Archives Canada. Our collections have a surprisingly large number of archival sources concerning the German mercenaries who fought during the American Revolution. We have nominal rolls of different regiments in manuscript groups MG11 and MG13; letters written by German officers in the Haldimand papers (MG21); and orders, correspondence and journals in MG23. Many of the microfilm reels containing these documents are digitized and available to the public through Héritage. We also have published sources on our German ancestors, with historical analysis, lists of soldiers and short biographies, mostly located in our Genealogy section. To learn more about our holdings on German mercenaries, visit Immigration: German.

Anik Laflèche is a student project assistant in the Public Services Branch of Library and Archives Canada.