Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Join us every month during 2017 as experts, from LAC, across Canada and even farther afield, provide additional insights on items from the exhibition. Each “guest curator” discusses one item, then adds another to the exhibition—virtually.

Be sure to visit Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? at 395 Wellington Street in Ottawa between June 5, 2017, and March 1, 2018. Admission is free.

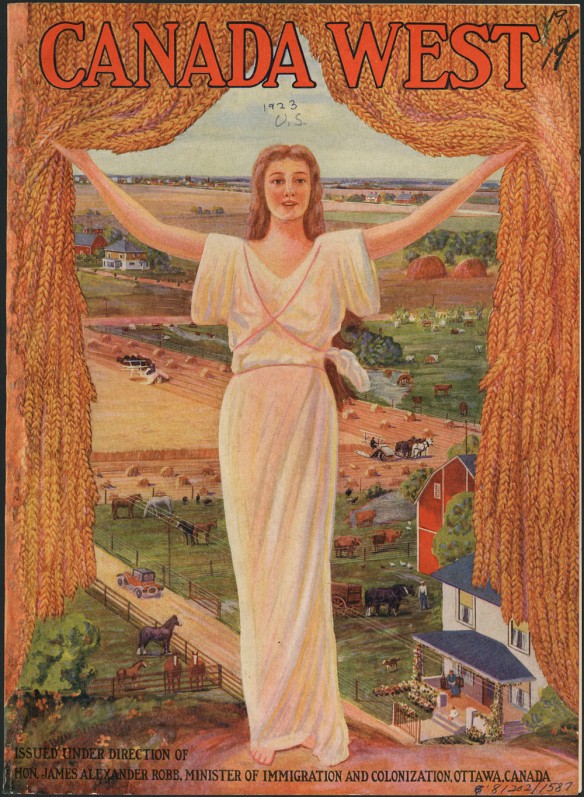

Cover from a Canada West immigration atlas published by the Department of Immigration, ca. 1923

Cover from a Canada West immigration atlas published by the Department of Immigration, ca. 1923 (MIKAN 183827)

Behind golden curtains of grain, we see an idealized—and inaccurate—vision of Canada. Mythologizing was common in immigration advertising. At the time, the west was just not as modern or developed as shown here.

Tell us about yourself

I was born and raised in London, Ontario as part of a close-knit Italian-Canadian family. My family’s stories about my culture inspired me to become passionate about the history of Italy.

As a result, I have travelled Italy and other parts of Europe on several occasions, and try to travel whenever I can. I had the privilege of travelling to England for school. While there, I participated in an archaeological dig along Hadrian’s Wall, and during my spare time, I was able to visit parts of northern England and Scotland. I have also travelled Europe with family and friends. During my travels, I always make an effort to visit as many historical and cultural institutions as I can. Visiting these sorts of places is interesting, as it shows you what society values.

My next travel mission is to try to see more of Canada. While I have done quite a bit of travelling outside of North America, I have never taken the time to see my country. I hope that with Canada’s sesquicentennial I will have an opportunity to look more at my country and see what sorts of things we value as Canadians.

Is there anything else about this item that you feel Canadians should know?

This Canada West cover is a terrific example of Canadian immigration posters from the 20th century. The Canadian Department of Immigration had begun an aggressive advertising campaign in the late 19th century hoping to attract immigrants to the sparsely populated Western provinces.

Promotional immigration poster “40,000 Men Needed in Western Canada” (MIKAN 2837964)

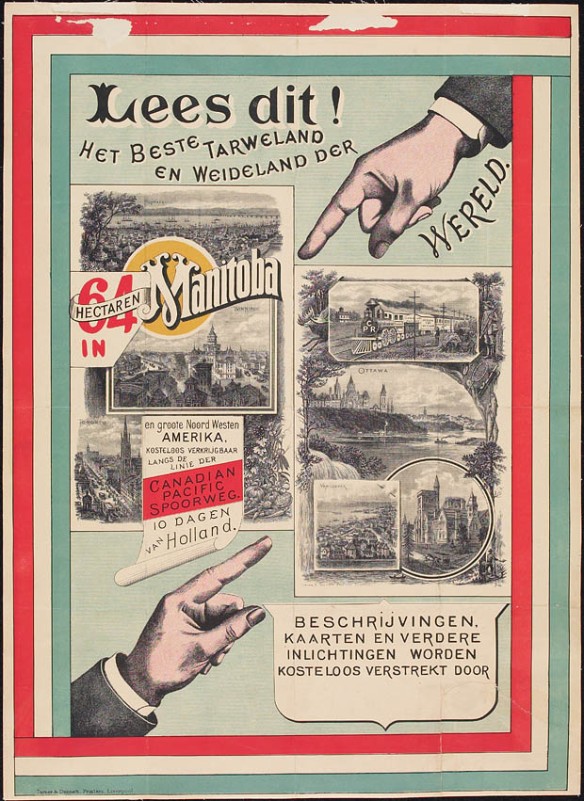

Canada and the British government originally sought to recruit English-speaking immigrants, with many advertisements circulated around the British Isles and the United States. The Department of Immigration did eventually diversify, but in the beginning still focused on white European countries as main sources for immigration. The Netherlands, Germany, and Austria-Hungary were the main targets of immigration campaigns, with text translated from English to other languages. The poster below is an example of promoting Manitoba as a viable area to settle Dutch immigrants.

Immigration poster “Lees Dit!” [Read this!] advertising Manitoba to Dutch immigrants, ca. 1890 (MIKAN 2837963)

Though these simplistic campaigns seem ineffective now, the Canadian Department of Immigration was successful. By 1911 immigration numbers were around 331, 288 per year. After the First World War, the numbers jumped to over 400,000 per year. Imaged-based advertisements, and the notion of Canada as a land of abundance were successful. These early endorsements sold Canada to people who identified as something other than Canadian. Though the images depicted in the propaganda, were not always realistic, they portrayed Canada as a land of opportunity and abundance.

Tell us about another related item that you would like to add to the exhibition

Canadian immigration and advertising has evolved substantially since the early 20th century. Our ideas of who is an immigrant, and why people choose to come to Canada has changed. How we document immigration has also changed. Technology such as photography and videography have been used to record immigration stories in the modern period.

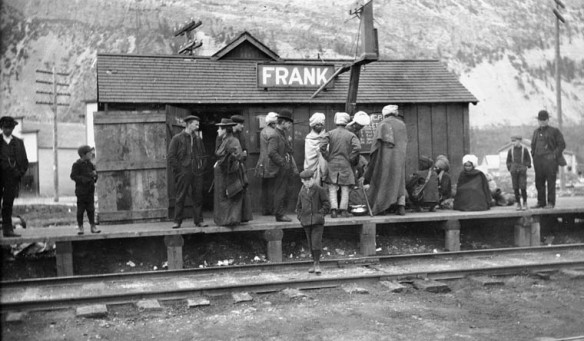

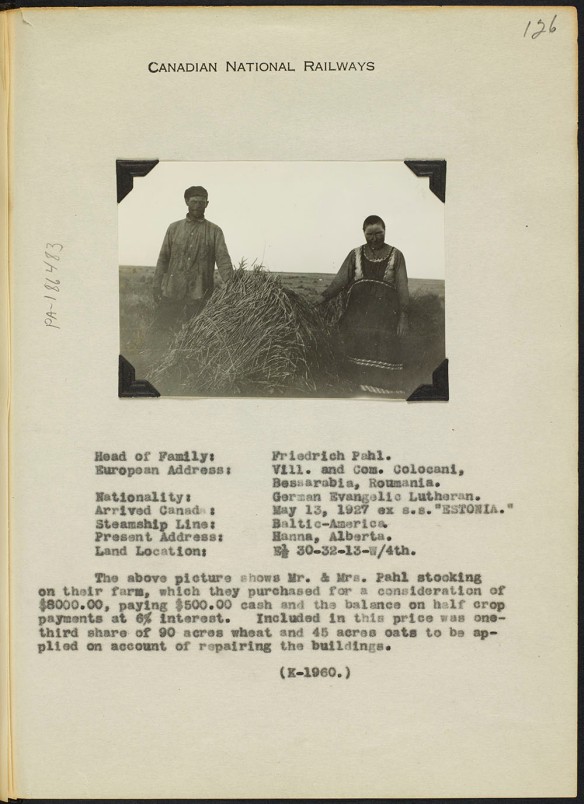

Library and Archives Canada has an amazing collection of contemporary photographs of immigrants ranging from the late 19th century to the present. These images often depict a different immigrant experience. Photos in the archives show that our immigration policies had a global impact. Many of the immigrants who arrived in Canada would not only work in rural areas, but in urban centers and have an impact on the way Canada has formed. Presently, Library and Archives Canada is working on adding more photos to their collection, highlighting the different materials in their collections. More modern photos like those in the exhibition join older photos like those shown here.

Group including Indian immigrants on platform of Canadian Pacific Railway station, Frank, Alberta. ca. 1903 (MIKAN 3367767)

Mr. and Mrs. Friedrich Pahl on their farm, Romanian immigrants who arrived May 13, 1927, aboard the S.S. Estonia, Baltic-America Steamship Line (MIKAN 3516853)

Library and Archives Canada also has a collection of videos and oral histories related to the immigrant experience. This collection includes videos on the history of Pier 21, one of the largest immigration points in Canada. These video testimonies show the changes in immigration trends, and how the idea of Canada is continually evolving. While we no longer see Canada as an expanse of open field, the idea behind immigration to Canada is the same. Canada is a land of opportunity for global people, and like our earlier poster, Canada is available for immigrants.

Biography

Nicoletta Michienzi has completed an undergraduate degree from the University of Western Ontario with an Honors Specialization in History and a Major in Classical Studies. During her degree, she participated in an archaeological dig in the north of England and was able to see the effects of tourism on historic sites. She continued her education at Western, completing a Master’s degree in Public History. Since graduation she has been employed by various historical institutions in London, Ontario. She is currently working as the Public Programmer at the Royal Canadian Regiment Museum and as a Historical Interpreter at Eldon House. At the Royal Canadian Regiment Museum, she organizes and conducts tours, educating the public about London’s military history and its connection to global conflict. At Eldon House, she interacts with tourists and helps conduct education programs about London’s oldest heritage home. At both institutions, she focuses on visitor services and educating the public, hopefully making visitors enthusiastic about the history of their community and their country.

Related Resources

Francis, Daniel. Selling Canada: Three Propaganda Campaigns that Shaped the Nation. Vancouver: Stanton Atkins & Dosil Publishers, c.2011.