By Kelly Anne Griffin

In the spring of 1919, tensions boiled over in Winnipeg. Social classes were divided by both wealth and status. Labourers gathered in a common front, and ideas about workers’ rights spread.

Canada’s largest strike and its greatest class confrontation began on May 15. Even though changes were slow to come in the aftermath of the six-week general strike, it was a turning point for the labour movement, not just in the city of Winnipeg but for workers across this sprawling country.

During those important weeks in 1919 Manitoba, workers fought peacefully and tirelessly for basic rights such as a living wage, safety at work and the right to be heard; these things are often easily taken for granted in our own day and age. The Winnipeg General Strike was a revolt of ordinary working-class citizens frustrated with an unreliable labour market, inflation and poor working conditions. Collectively they fought, and united they stood.

The perfect storm

The labour market in Canada was precarious in 1919. Times were difficult for skilled labour, and inflation made it harder and harder for workers to make ends meet. For example, in the year 1913, the cost of living rose by 64 percent. In addition to insecure employment and inflation, the success of the Russian Revolution in 1917 contributed to unrest among workers.

Unions were gaining traction in Canada and growing quickly. As a result, labour leaders met in an attempt to form One Big Union. Although unions had become more common, employers did not recognize bargaining rights.

The First World War also contributed to what happened in Winnipeg in spring 1919. The length and magnitude of that war inevitably resulted in many changes for the economy and an increase in employment at home. But when the war ended, production dropped, and a rush of returning soldiers struggled not only to adjust to civilian life but also to find jobs.

Work was scarce in the once-booming prairie city. Some returning soldiers also viewed immigrants as having taken jobs that should have been theirs instead. Many Canadians, both soldiers and civilians, had sacrificed much during the war, and many thought that their reward would be a better life. Instead, at war’s end, their hardships increased as they faced unemployment, inflation and an unstable economic outlook.

On May 1, 1919, building workers in Manitoba declared a strike after many futile attempts at negotiation. They were followed the next day by metalworkers. Two weeks later, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council called for a general strike.

On the morning of May 15, telephone operators in Winnipeg did not report for work. Factories and storefronts remained closed, mail service stopped, and transportation ground to a halt. Over the next six weeks, around 30,000 workers, both unionized and non-unionized, took to the streets and made their sacrifices for the greater good.

Strikers gathered peacefully on the streets for six weeks in 1919, standing as one to fight for basic labour rights that we often take for granted today. (a202201)

A city divided will not stand

The strikers were orderly and peaceful, but the reaction from the government and employers was often hostile. As is the case with any labour dispute, the views of the working class and the views of the ruling class were very different. Some attempts were made to bridge the communication gap in the lead-up to the strike, to no avail.

The social setting in the city at the time aggravated the situation. Though strikes were not new—in 1918, for example, North America had a record number of strikes—the events in Winnipeg were unprecedented in size, nature and the seeming determination of those on strike.

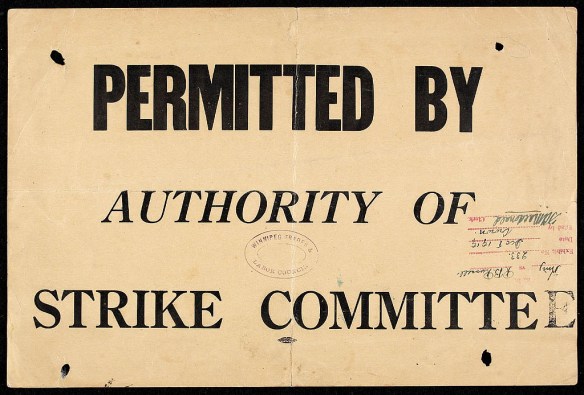

The Central Strike Committee, which represented all of the unions affiliated with the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, was tasked with communication and keeping order in the city. The lack of services because of the strike caused suffering for many poor families. To tackle this, the committee authorized operation permits, as seen here, for essential services. (e000008173)

The Central Strike Committee, made up of representatives from each of the unions, was created to negotiate on behalf of the workers and to coordinate essential services during the strike. The Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand was the organized opposition from the government and employers. From the outset, the Citizens’ Committee ignored the strikers’ demands. The strikers were portrayed in the media as a revolutionary conspiracy, a dangerous radical uprising based on Bolshevik extremism.

There were many displays of solidarity across the country in the form of sympathy strikes. The issues that had reached a boiling point in Winnipeg were manifest across the country, and these acts of support were of great concern to the government, and to employers throughout Canada. This fear saw the government finally intervene in the strike.

The Citizens’ Committee held the firm view that immigrants were largely to blame for the strike. As a result, the Canadian government amended the Immigration Act to allow British-born immigrants to be deported. The definition of sedition in the Criminal Code (controversial section 98, repealed in 1936) was broadened so that more charges could be laid. The government’s actions also included jailing seven Winnipeg strike leaders on June 17, who were eventually convicted of a conspiracy to overthrow the government and sentenced to prison terms ranging from six months to two years.

Saturday, Bloody Saturday

On June 21, 1919, the strike reached a tragic boiling point. Main Street in Winnipeg was a scene of unprecedented upheaval.

On June 21, 1919, crowds gathered outside the Union Bank of Canada building on Main Street. By the end of the day, 2 strikers were dead and 34 wounded in what became known as Bloody Saturday. (a163001)

The normally peaceful demonstrations took a violent turn. Strikers overturned a streetcar and set it ablaze. The Royal North-West Mounted Police and the newly created Special Police Force, astride their horses and heavily armed, waded through the crowd swinging bats and wielding wagon spokes as weaponry. Machine guns were also used. Two strikers were killed, 34 wounded, and the police made a total of 94 arrests. Western Labor News, the official publication of the movement, was shut down. Five days later, feeling dejected and fearful of what they had witnessed on Bloody Saturday, the strikers ended their efforts for change.

On Bloody Saturday, the usually peaceful demonstrations turned violent. Strikers overturned a streetcar and set it on fire, and the authorities escalated the situation. (e004666106)

Short-term pain for long-term gain

Those who have been on strike will attest to the struggle of living on strike pay. The extent and duration of the Winnipeg General Strike reflect the deep passion, and anger over their plight, of the workers at the time.

As we consider the history 100 years later, what do we see as the legacy of the events that unfolded over six weeks in Winnipeg?

At the end of the strike, the workers won very little for their valiant efforts, and some were even imprisoned. It would take nearly 30 more years for Canadian workers to secure union recognition and collective bargaining rights. To add insult to injury, the immediate situation in Winnipeg worsened, with the economy in decline. The tensions and sentiments that led to the uprising lingered, which caused increasing divisiveness in labour relations in the city.

Still, it is undeniable that the strikers’ fight helped to pave the way for where we are today. The provincial election in Manitoba the following year, 1920, saw 11 labour candidates win seats, a positive step toward legislative change. Strike leader J.S. Woodsworth, who was imprisoned for a year because of his leadership during the strike, founded the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, predecessor of today’s New Democratic Party.

The arrest of leaders of the Winnipeg General Strike in June 17 led to Bloody Sunday. Here, a group of demonstrators protest the trials of the men arrested. (C-037329)

Although the strike ended without the desired gains, the ideals it stood for live on. Workers in Winnipeg rallied around the common challenges faced despite differences in race, language or creed. A century later, Canada has made great strides regarding workers’ rights, and much of this is thanks to the solidarity and resilience of the general strikers in Winnipeg during that fateful spring in 1919.

Kelly Anne Griffin is an archival assistant in the Science and Governance Private Archives Division of the Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada.