This blog is part of our Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada series.

Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada is free of charge and can be downloaded from Apple Books (iBooks format) or from LAC’s website (EPUB format). An online version can be viewed on a desktop, tablet or mobile web browser without requiring a plug-in.

By Ryan Courchene

The archival and published collections held at Library and Archives Canada (LAC) are amazing, and so extensive that you will never be able to see them all. You can find hidden gems every single day just by looking, either online on LAC’s website, or in one of the several buildings with archival holdings across Canada.

I work in the Winnipeg office, which alone holds over 30,000 linear feet (nearly 9,150 metres) of archival records. On a business trip to Ottawa in 2016, I had the opportunity to shadow the reference service employees at 395 Wellington Street. While there, I noticed three catalogue drawers near the desk and inquired about what they contained.

The reference room at LAC in Ottawa, seen from the hallway. The catalogue drawers containing research cards with copies of photographs can be seen on the left of the room. Photo Credit: Tom Thompson

Reference room catalogue drawers, organized by subject headings and geographical locations, containing research cards with copies of photographs held in the collections at LAC in Ottawa. Photo Credit: Tom Thompson

I was told that they held small cards with images in the collection that were copied from microfilm and microfiche. Intrigued, I decided to look at some of the cards on my lunch break. I soon discovered the “Birth of the West” collection, which contains hundreds of incredible photographs of Western Canada, with many focusing on Indigenous images by Ernest Brown. I learned that the images contained in the drawers were only card copies of the originals; the images themselves are small and of poor quality. From a researcher’s perspective, this can be both frustrating and helpful when conducting on-site research. As with this image of the moose, many photographs indexed in the card catalogues have never been digitized. In these situations, the cards provide immediate access to images without having to order the original material in off-site storage.

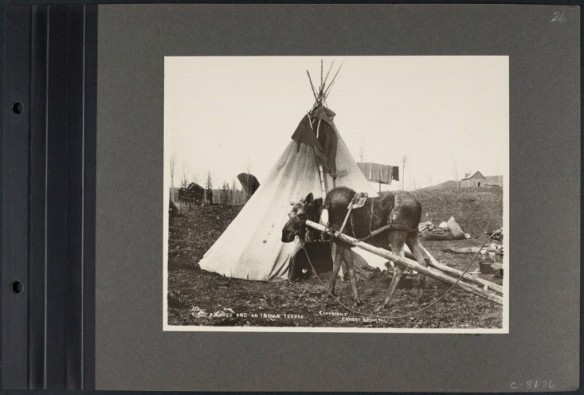

The photographs in this noteworthy collection are not only visually stunning but also remarkable for the wealth of historical information on Canada and the First Nations peoples of the West. Even though there are hundreds of images in the collection, one image really caught my eye. It tells a fascinating story that evolves every time I examine it.

Catalogue card of a copy of a photograph of a young moose with a harness hitched to a travois and standing in front of a teepee, unknown location, ca. 1870–1910. Photo Credit: Tom Thompson

This photograph depicts a small home, which could belong to a Métis or First Nation family, blankets hung to dry, some cleared tree brush, a pot of food by the fire pit, a beautiful teepee, and of course a domesticated young moose with a harness hitched to a travois. The one item that I did not notice immediately, which is probably the most important part of the image, is the hand holding the rope attached to the moose. My grandfather used to tell me about how he cleared his own land so he could farm and raise cattle. Is this what was happening here? Or was something else going on? Each time I look at the image, a new story emerges that raises more questions.

Detail of the photograph of a young moose with a harness hitched to a travois and standing in front of a teepee, unknown location, ca. 1870–1910. Photo Credit: Tom Thompson

After seeing this image of the young moose, I wanted a copy for myself. Since I was working backwards, I had to find the image in the collection to see if it was already digitized, and if not, verify any restrictions on getting a copy. To my disappointment, I found that it was not digitized, and I decided not to push the request any further.

It was not until 2019 that I learned the Ernest Brown collection was being digitized by the We Are Here: Sharing Stories (WAHSS) initiative. The moose photograph is one of 126 images in an album entitled “Birth of the West.” Dating from ca. 1870–1910, the album consists of photographs taken in the Northwest Territories (now Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Nunavut) and British Columbia. In addition to fully digitizing and describing this album, the WAHSS team has digitized over 450,000 images, including photographic records, textual documents and maps, with the goal of providing free online access to primary sources, no travel required!

In October 2019, I was finally able to order a copy. It fills me with great joy to know that I have the first print from the digitized copy of this amazing image, which hangs in my office today.

Young moose with a harness hitched to a travois, unknown location, ca. 1870–1910. This photograph is on page 28 of the “Birth of the West” album. (e011303100-028)

Ryan Courchene is an archivist in the Indigenous Initiatives division at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg?w=584)