By Ariane Gauthier

We make surprising connections throughout our lives. Things we thought were confined to our work or social circles unexpectedly surface in other areas. For me, several long drives with my husband to Northern Ontario led me to learn more about the Kapuskasing internment camp. Few people know that there were internment camps in Canada during both world wars. And even fewer know that these camps were not all for prisoners of war—many detained Canadian civilians of so-called “enemy” nationality.

The Kapuskasing camp was active from the start of the First World War in 1914 until 1920. It mainly held Ukrainian civilians. They were sentenced to forced labour, including constructing buildings and clearing several hectares of surrounding forests so the government could establish an experimental farm.

The Kapuskasing internment camp. (e011196906)

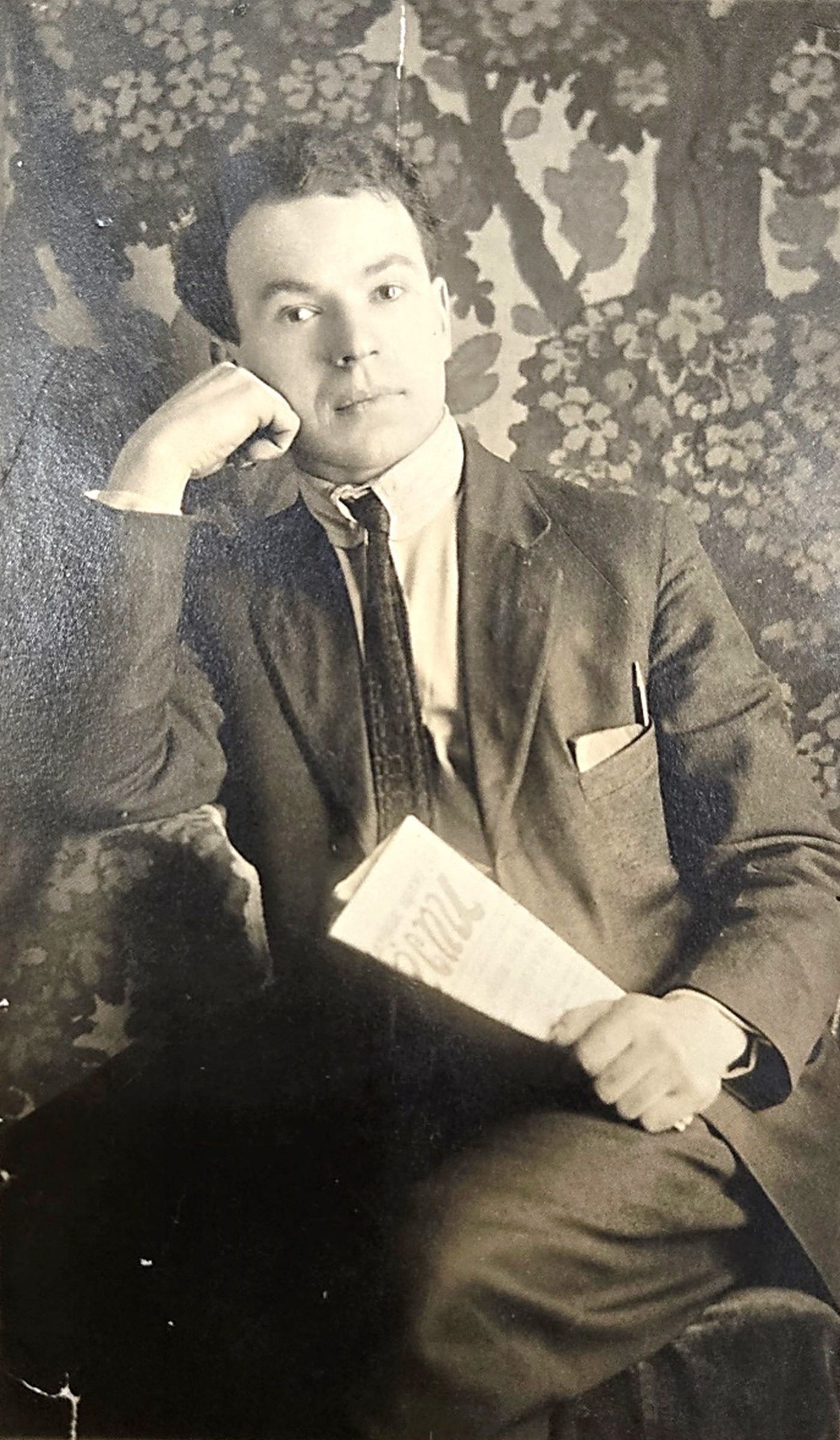

My work as a reference archivist has allowed me to delve deeper into the resources of Library and Archives Canada to learn more about this grim period in Canadian history. During my research, I came across the documents of William Doskoch, born on April 5, 1893, in Laza, Galicia, a territory of the Austro‑Hungarian Empire that is now part of Ukraine.

In 1910, at the age of 17, William Doskoch joined his brother in Canada to work in the coal mines in Nanaimo, British Columbia. While he was in Vancouver in 1915, he was arrested, as he was considered an enemy alien. He was interned in several camps: first at Morrissey, then at Mara Lake, and later at Vernon, before finally being transferred to Kapuskasing. It was from there that he was released five years later, on January 9, 1920.

The William Doskoch fonds is rich in resources that help us understand internment camps from an internee’s perspective. While it contains information on several camps, I was mainly interested in William’s notes about Kapuskasing. According to his writings, the conditions were similar to those at Vernon: mistreatment of prisoners, random executions, many cases of tuberculosis, and inadequate internment conditions for the cold weather.

Portrait of William Doskoch. (MIKAN 107187)

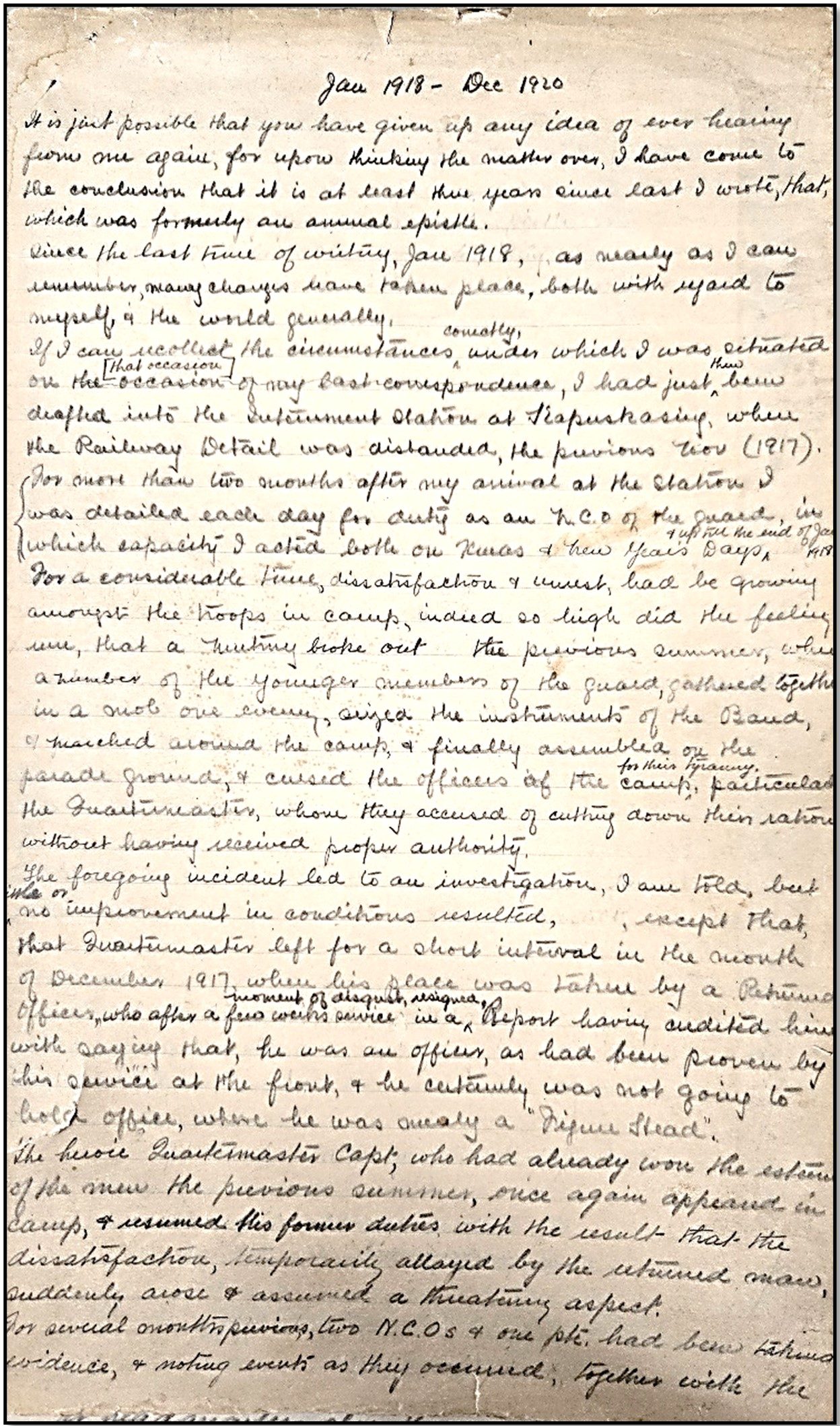

I also found a letter written by George Macoun, a guard at the Kapuskasing camp, detailing events that occurred there between November 1917 and the summer of 1919. Although of lesser magnitude than the William Doskoch fonds, the letter provides us with a rare glimpse into the experience of an internment camp guard.

Letter from George Macoun, a guard at the Kapuskasing internment camp. (MIKAN 102082)

Originally from Ireland, George Macoun immigrated to Canada, where he joined the militia in February 1915. This is how he became involved in the operations at the Kapuskasing internment camp. He wrote this letter after the war ended, following his dismissal as a guard. Reminiscent of a memoir, he recalls the significant experiences of his time in Kapuskasing, including the conflicts and tensions among the guards due to abuses of power. He recounts the following:

“One little incident took place in March 1918, which aroused the wrath of the company generally against this commander owing to the manner in which the case was brought up being considered, according to military custom, absolutely irregular. One evening, whilst an entertainment was being held in the recreation room about the last week of Feb 1918 a certain corporal, one of the most popular men of the guard had the misfortune to get drunk and a disturbance during the night, not only in his own room but also in one of the other rooms. This information was conveyed to the popular O.C. [officer commanding] by some weak about two weeks later, when a charge was at once laid against the corporal.”

The Department of the Secretary of State of Canada fonds also contains a wealth of information. Notably, it includes a sub‑series entitled Custodian of Enemy Property and Internment Operations records, covering the period from 1914 to 1951 (R174-59-6-E, RG6-H-1). During both world wars, the Secretary of State was responsible for, among other things, matters arising from internment operations. However, some activities, such as those related to the management of properties confiscated by the State from internees, were eventually transferred to other departments over the years. The fonds still contains documentation on the certificates of release from internment camps and on the administration of the camps. Boxes 760 to 765 inclusively hold documents concerning the operations of the Kapuskasing camp.

Because there’s a lot of information, I will only focus on a few interesting elements for Kapuskasing. For example:

- According to correspondence from the director of internment operations, the experimental farm built by the prisoners at Kapuskasing was completed in early December 1917.

- According to statistics from December 1918, the camp housed the following prisoners: 607 Germans, 371 Austrians, 7 Turks, 5 Bulgarians, and 6 classified as “other.” A note suggests that the term “other” was used for prisoners of war, but it is not clear.

- Several letters written by prisoners to their family members were censored. This is the case for the letters that Adolf Hundt sent to his wife. Discouraged by the extent of censorship, he gave up writing to her, leading his wife to worry about his health.

This blog post gives you an overview of the information available about the Kapuskasing camp in the Library and Archives Canada collection. This rich resource offers valuable insights into this troubling chapter of Canadian history. To support further research, we have created a guide on internment camps in Canada during the two world wars, which was very helpful to me in writing this blog post.

To consult the guide, follow this link:

- Thematic research guides on internment camps

Ariane Gauthier is a reference archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.