By John Morden

This week in the blog series on Canadian Victoria Cross recipients, we honour corporal Thomas Kaeble, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his valour on the battlefield on June 8 and 9, 1918. His actions took place 100 years ago today.

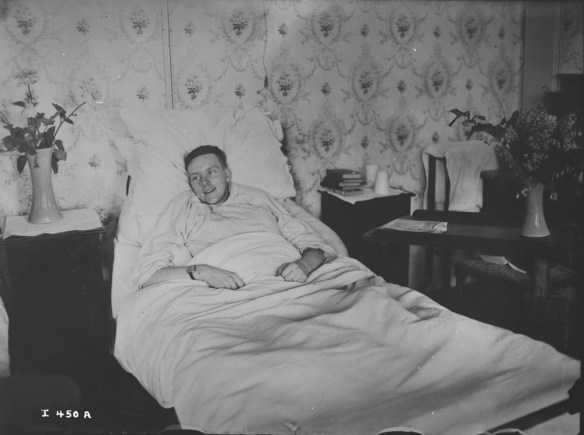

Joseph Thomas Kaeble was born on May 5, 1893, in Saint Moise, Quebec. Prior to the First World War, he served as a machinist. He enlisted in the 189th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force on March 20, 1916, and on November 12, 1916, transferred to the 22nd French Canadian Battalion. The following year, in April, Kaeble was wounded and admitted to hospital. He was released from hospital shortly after, in May. While in hospital, he was promoted to the rank of corporal.

Joseph Kaeble, undated. Source: Directorate of History and Heritage.

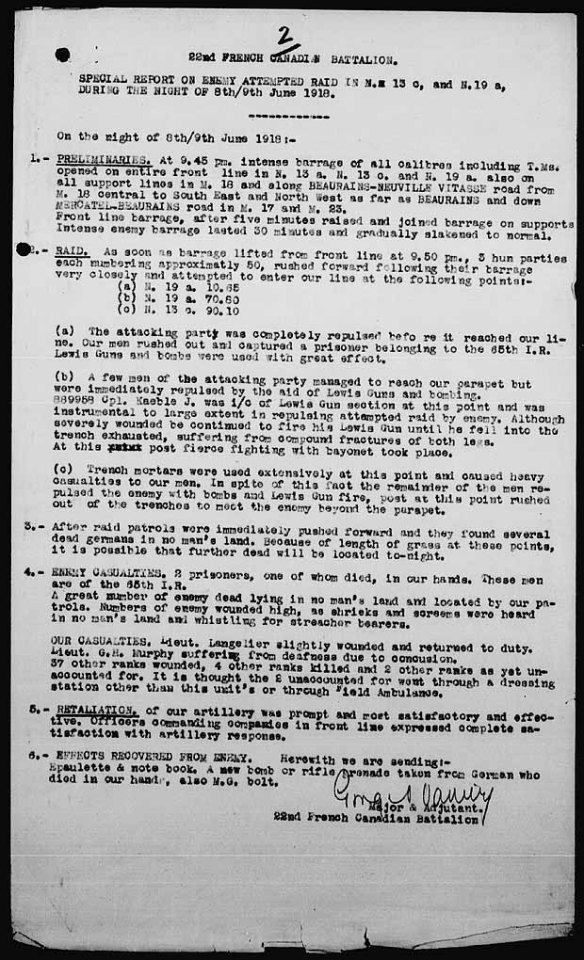

Kaeble earned the Victoria Cross during the 1918 Spring Offensive, Germany’s last gamble for victory on the Western Front. On the evening of June 8, 1918, while the 22nd Battalion was stationed near Neuville-Vitasse in France, the German army launched a raid against the Canadian lines. The attack was preluded by a blistering German bombardment, which left the Canadians stunned. Afterwards, a wave of 50 German soldiers came towards Kaeble’s position. With most of his comrades injured from the bombardment, Kaeble got out of the parapet, and, with a Lewis machine gun, held off the German onslaught on his own. Despite being hit several times, he held the attackers at bay until he was finally knocked back into his trench, severely wounded. While laying wounded, he was reported to have said to his brothers in arms: “Keep it up boys; do no let them get through! We must stop them!” (London Gazette, 30903, September 16, 1918)

In that battle, Kaeble suffered compound fractures in both legs, both arms, as well as a fractured hand and neck. In the end, the German raid was repulsed by the 22nd, to large extent because of Kaeble’s valiant stand.

in the 22nd Canadian Infantry Battalion War Diary on the actions that took place on June 8 and 9, 1918 (e000963629)

Corporal Kaeble would die of his grievous wounds on June 9, 1918. Along with the Victoria Cross, he was also awarded the Military Medal for his actions in France. He was the first French Canadian to be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Kaeble’s grave, Wanquetin, France. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Credit: Wernervc

Kaeble’s legacy holds strong in Canada. He is honoured, among others, with a bust in Ottawa’s Valiants Memorial. In November of 2012, a new patrol vessel, the CCGS Caporal Kaeble V.C., was presented to the Canadian Coast Guard.

Library and Archives of Canada holds the digitized service file of Corporal Joseph Kaeble.

John Morden is an honours history student from Carleton University doing a practicum in the Online Content Division at Library and Archives Canada.