By Ariane Gauthier

Photo of Sulo W. Alanen as it appeared in a Finnish newspaper announcing his death. (Source: Canadian Virtual War Memorial)

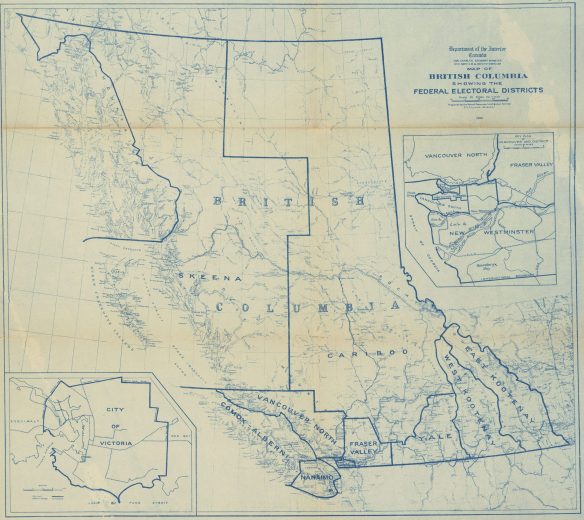

The story of Sulo W. Alanen begins in the northern Ontarian village of Nolalu, a small settlement outside of Thunder Bay that emerged largely due to the arrival of Finnish settlers in the region. These settlers were likely drawn to the thriving lumber industry, the opportunities for farming, and the convenience of the railway passing through Nolalu.

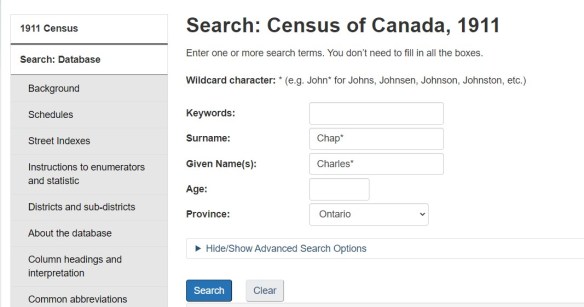

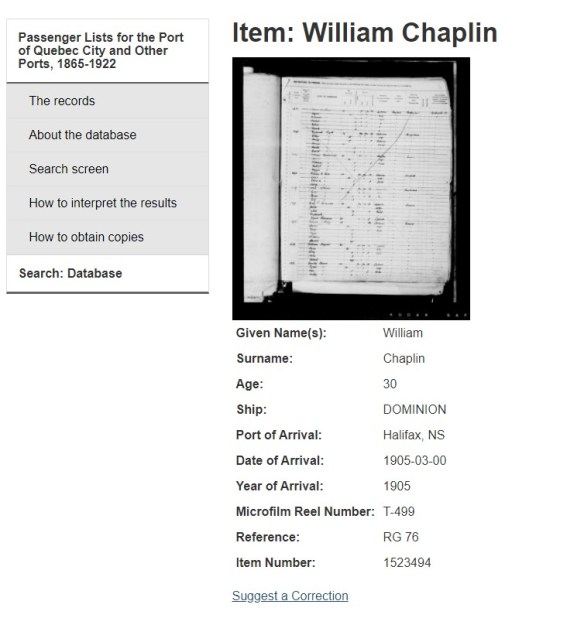

Matti Alanen, originally from Jurva, Finland, was one of these immigrants who braved the journey to Canada in 1904, inspired by the promise of a better life. Like many of his compatriots, he settled in Nolalu, a growing Finnish community established just four years earlier. Here, he found familiarity in an unfamiliar land, with a supportive network of fellow Finns. Matti embraced farming as his livelihood. Hilma Lehtiniemi, originally from Ikaalinen, Finland, followed her family to Canada in 1908. After arriving in Nolalu, she met and married Matti, likely around 1910, as suggested by Sulo’s service file, which mentions their marriage in April 1910 in Port Arthur, Ontario.

Sulo, the couple’s third son and child, was born May 13, 1914, in Silver Mountain, Ontario, a mining settlement near Nolalu. The Alanen family’s farmstead appears to have been located between these two communities, as their place of residence alternates between Silver Mountain and Nolalu in Sulo’s service file.

Silver Mountain mining settlement, 1888. (Source: a045569)

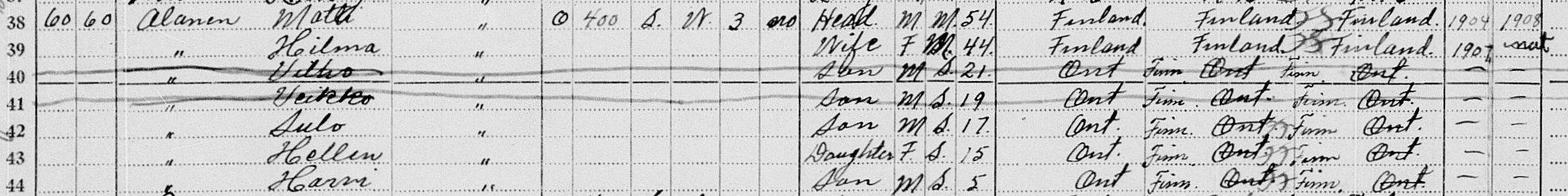

Sulo was the middle child among five siblings. The 1931 Census provides insight into his upbringing, indicating that Finnish was his first language. This is unsurprising, given that Nolalu was a Finnish community where most settlers shared this cultural heritage. Census entries for neighbouring households confirm this pattern: nearly all family heads were originally from Finland and spoke Finnish as their first language.

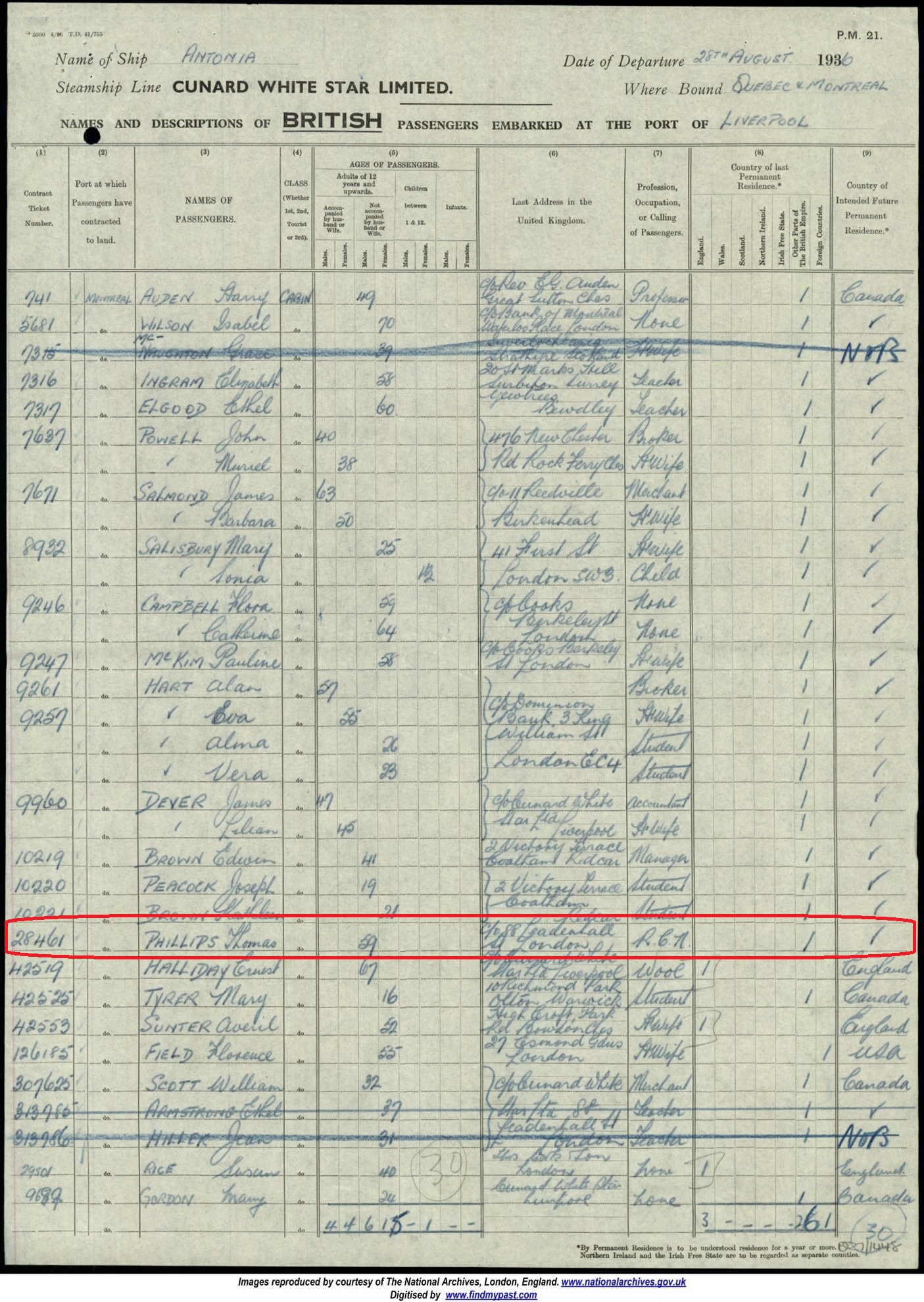

A screenshot of the 1931 Census featuring the Alanen family. Sulo’s name can be seen on line 42 of the 5th page. (Source: e011639213)

English came later for Sulo and his siblings, likely as a result of simply living in Canada, as none of them attended school or learned how to write. Much of Sulo’s childhood was spent working on the family farm. In adulthood, he continued working on his father’s farm until his enlistment for the Second World War. His service file also mentions that he occasionally worked as a bushman for extra income.

Sulo was forced to serve at the 102 Canadian Basic Training Camp in Fort William under the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA), enacted in 1941 by the King government as a compromise to avoid full conscription. The NRMA mandated that able-bodied men contribute to Canada’s defence and national security. After serving for 30 days under this program, Sulo made the pivotal decision to enlist voluntarily on May 4, 1943.

Sulo’s enlistment in the Canadian Army aligned with the critical Allied preparations for the D-Day landings, planned for the summer of 1944. From his initial training at Camp Shilo in Manitoba to boarding a ship bound for England, his focus was singular: preparing for the storming of Juno Beach.

Sulo’s ship arrived in England on April 11, 1944—just two months before Operation Overlord. On April 27, he was assigned to the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, specifically to the 2nd Canadian Base Reinforcement Group. This designation indicates that Sulo was not initially slated to participate in the first assault wave. Instead, as a part of C Company, he was positioned to join the Royal Winnipeg Rifles after they had pierced the Atlantic Wall.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ war diary tells us what D-Day was like for Sulo and his comrades. The troops were informed at 9 p.m. the evening before that Operation Overlord was on, and all were fairly enthusiastic. The diary states: “There was an air of expectancy and sense of adventure on all craft this night, the eve of the day we had trained for so hard and long in England.”

The long day began at 4 a.m. with tea and a cold snack. The weather was cloudy and the sea was heavy. At 5:15 a.m., landing crafts were lowered from the motor vessel Llangibby Castle, still about 15 kilometres from the coast. At 6:55 a.m., the Royal Navy and air support began bombarding the coastline of France. The landing crafts arrived on shore around 7:49 a.m. with B and D companies landing first. As the war diary grimly notes: “The bombardment having failed to kill a single German or silence one weapon, these coys had to storm their positions “cold”—and did so without hesitation.”

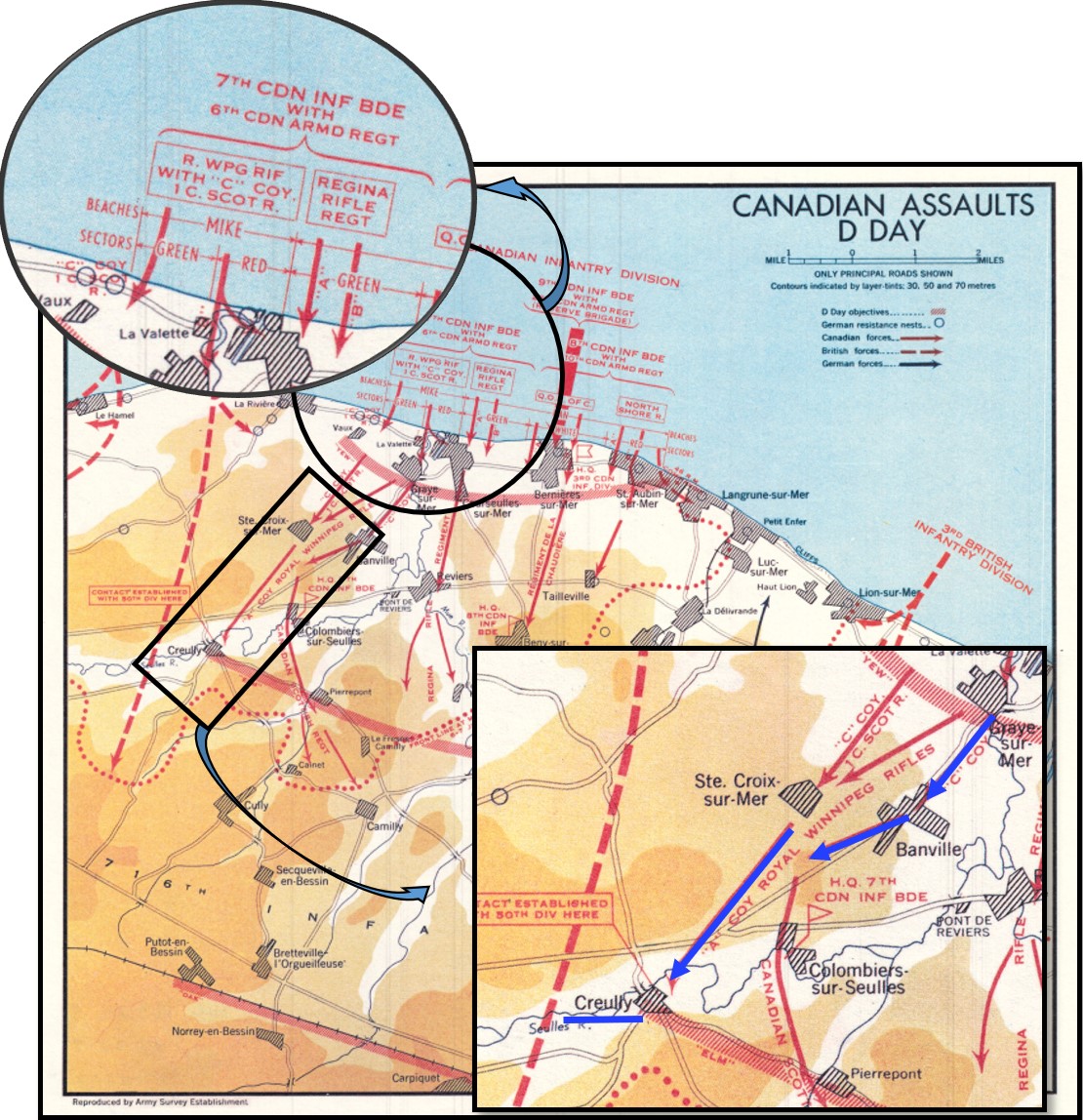

A and C companies landed later around 9 a.m. C Company disembarked on the Mike and Love sectors of Juno Beach, where the beach and surrounding dunes were still under heavy mortar fire. Pinned down for about two hours, the soldiers eventually regrouped and, alongside A Company, pushed forward towards their objective, Banville, encountering several pockets of resistance en route but overcoming each one until just south of Banville, where the enemy had dug in on commanding ground.

Map of Juno Beach showing the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division’s movements on D-Day. (Source: e999922605-u)

The first day of the Battle of Normandy brought surviving members of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles to Creully by 5 p.m., completing phase II of Operation Overlord. Little rest was had, especially for C Company, which faced an enemy patrol attack at 2 a.m. The soldiers repelled the assault and captured 19 German prisoners, allowing for a brief respite until 6:15 a.m., when they were ordered to advance once more. Their next objective was the OAK Line at Putot-en-Bessin.

This event set the tone for the Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ grueling experience in the aftermath of D-Day as they encountered some of the most ferocious and obstinate resistance by German forces.

Army Numerical 35899-36430—Northwest Europe—Album 75 of 110. (Source: e011192295)

By July 5, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles had painstakingly made it to the village of Marcelet, where they engaged in the battle for Carpiquet. While Sulo’s service file does not delve into the specifics of the injuries that ended his life on that day, the war diary tells us his regiment was subjected to enemy shelling and strafing from the air during the whole day. In this chaos, Sulo was either struck by shrapnel or collapsing buildings. Initially, he couldn’t be found and was reported missing, but when the battle calmed just enough by July 5, his body was discovered, and he was officially reported killed in action.

Like so many Canadians who gave their lives during D-Day and the battle of Normandy, Sulo W. Alanen rests at the Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery in Calvados, France. He is buried in plot XV. G. 16, where his name liveth for evermore.

For more reading on this subject:

- The Life of Private Marcel Gauthier (Part 1), by Ariane Gauthier, Library and Archives Canada’s Blog

- The Life of Private Marcel Gauthier (Part 2), by Ariane Gauthier, Library and Archives Canada’s Blog

- Have you heard of Léo Major, the liberator of Zwolle?, by Gilles Bertrand, Library and Archives Canada’s Blog

Ariane Gauthier is a reference archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.