By Kyle Huth

I first saw the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow when I was 10 years old. It was on the cover of a book in a bookstore in Bobcaygeon, Ontario, some 40-plus years after the last Arrow had flown. Something about this sleek-looking white jet in Canadian markings climbing skyward captivated me. I would spend the rest of that family vacation poring over my newly purchased book; I wanted to learn everything I could about the Arrow! From an early age, I, like so many other Canadians, had my imagination captured by the Arrow.

The first Arrow, serial number 25201, was rolled out of the Avro Canada aircraft manufacturing plant in Malton (present-day Mississauga), Ontario, and unveiled to the public on October 4, 1957. A product of the Cold War, this large twin-engined delta-winged jet interceptor was designed to guard Canadian cities against the threat of Soviet jet bomber aircraft attacking from over the North Pole.

The rollout of the first Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow in Malton, Ontario, October 4, 1957. The people in the crowd give a sense of the size of the aircraft. (e999912501)

Avro Canada began design work on the Arrow in 1953, and by the end of the year, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) had ordered two developmental prototypes. The RCAF wanted an aircraft that could operate at Mach 1.5, at an altitude of at least 50,000 feet, and be armed with the latest array of guided missiles. At the time, no aircraft company in the United States, the United Kingdom or France had an aircraft in production or on the drawing board that could meet these requirements.

As Cold War tensions increased, so did the need for the Arrow. Soviet long-range jet bomber development was proceeding faster than expected, threatening to make the RCAF’s current jet interceptors obsolete. In 1955, the RCAF increased its order to 5 pre-production flight test Arrow Mk. 1s and 32 production Arrow Mk. 2s. The urgent need for the Arrow meant that it would go straight into production, skipping the traditional development phase for an aircraft of its type.

The Arrow Mk. 2, the production variant destined for RCAF squadron service, was to be powered by two Canadian-built Orenda Engines PS-13 Iroquois turbojet engines and equipped with the Astra I weapons control system and Sparrow II missiles. All three would be developed alongside the airframe, adding extra costs to the Arrow program. To avoid delaying the program, the Arrow Mk. 1s that were used to evaluate the design’s flight and handling characteristics were powered by two American-built Pratt & Whitney J-75 turbojet engines.

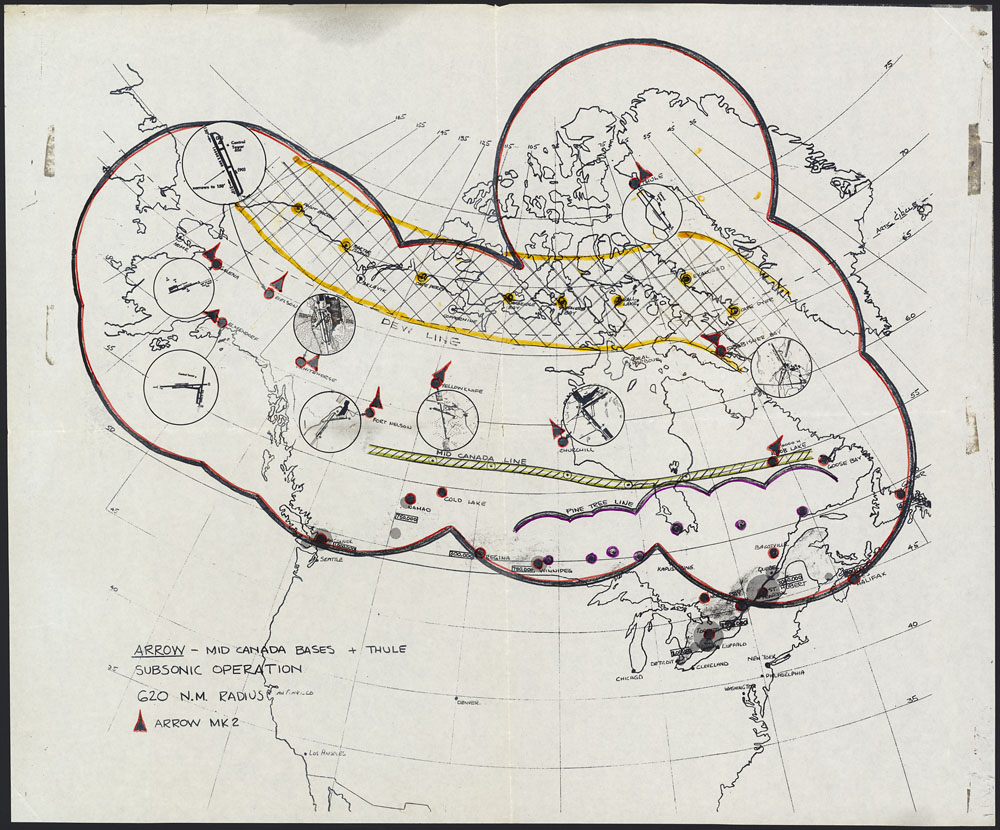

A map showing the subsonic operational range and proposed bases in Canada, Alaska, and Greenland for the Arrow Mk. 2, as well as other RCAF airbases (red). The locations of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line (yellow), Mid-Canada Line (green) and Pine Tree Line (purple) radar sites are also shown. (e011202368)

After five months of ground testing, Arrow 25201 took to the air on March 25, 1958, with famous test pilot Janusz Zurakowski at the controls. Over the next 11 months, four additional Arrow Mk. 1s would join the flight test program, with the Arrow Mk. 2, equipped with the more powerful Iroquois engines, slated to fly in March 1959.

While the flight test program was proceeding mostly as planned, and test pilots commenting positively about the performance and handling of the Arrow Mk. 1, behind the scenes, all was not going well for the Arrow program.

As development costs rose, the program was coming under increased financial scrutiny from Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s newly elected Progressive Conservative government. At the same time, Soviet rocket development had overtaken the West, (they launched Sputnik 1 the same day the Arrow was unveiled to the public) and it now appeared that Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles, not bombers were the main threat facing Canada. This technological shift cast doubts over the need for the Arrow and, there were those, such as the Minister of National Defence, George Pearkes, who questioned the need for manned interceptor aircraft altogether, believing that anti-aircraft missiles could replace them for a fraction of the cost. In September 1958, the government announced that it would order the Boeing CIM-10B Super Bomarc long-range surface-to-air missile, and it cancelled the Arrow’s troubled Astra I weapons control system and the Sparrow II missile program. Furthermore, the government notified Avro Canada that the rest of the Arrow program was up for review in March 1959.

On February 20, 1959, Diefenbaker announced to the House of Commons that the Arrow program was cancelled. In response, Avro Canada immediately terminated the 14,500 employees who were working on the program, claiming the company had been caught off guard by the government’s announcement.

“Better get one of these in memory of the plane that will never see the air,” quips recently laid off Avro Canada employee Pat Gallacher as he holds up the Arrow model kit he purchased at the Malton plant’s hobby store on February 20, 1959. (e999911901)

At the time of the cancellation, the five existing Arrows had flown 66 times and chalked up a total of 69:50 flying hours. The first Iroquois engine powered Arrow, 25206, was 98 percent complete on the day of the government’s announcement. Attempts to save one or more of the five completed Arrows for use as high-speed test aircraft failed. In the end, all completed aircraft, along with those on the assembly line, as well as the related drawings, were ordered destroyed on May 15, 1959. The Cabinet and Canada’s Defence Chiefs of Staff cited security concerns over the advanced nature of the aircraft and the classified material involved in the project as the reasoning behind the order. Arrow 25201 made the last flight of any Arrow on the afternoon of February 19, 1959, the day before the announcement of the Arrow’s cancellation.

Arrows 25202, 25205, 25201, 25204 and 25203 (from top to bottom) await their fate outside Avro Canada’s experimental building in Malton, Ontario, May 8, 1959. Three straight-winged Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck jet interceptors, the aircraft type that the Arrow was meant to replace, are parked alongside the Arrows. (e999911909)

The Arrow would not end up fulfilling its intended purpose of patrolling Canadian skies; instead, its impact on Canada would be a cultural one. Since its cancellation, the Arrow has been the subject of countless books, magazine articles and documentaries, as well as starring in its own CBC miniseries alongside Dan Aykroyd in 1997. The largest remaining pieces of the Arrow are the nose section of 25206 and the wing tips of 25203, held by the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. To this day, the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow continues to be a symbol of Canadian achievement, a source of much debate and speculation, and a point of pride and fascination for Canadians.

To learn more about the Avro Arrow, check out the following Library and Archives Canada resources:

- Podcast episode

- Flickr album

- Thematic guide

Kyle Huth is an archival assistant in the Government Records Initiatives Division at Library and Archives Canada.