By Rebecca Murray

From fantasy to historical fiction, contemporary authors are incorporating the topic of banned and challenged books in their writing. In Rebecca Yarros’s popular Fourth Wing, a would-be archivist is thrust into the perilous world of dragon riders and, along the way (spoiler), uncovers the truth about a “rare” (i.e., banned) book passed down through her family. Meanwhile, Kate Thompson’s The Wartime Book Club follows a courageous librarian in German-occupied Jersey who smuggles books to her neighbours during the Second World War. Through these tales, both authors bring the issue of censorship to the forefront, celebrating heroines who share forbidden stories and defend the right to read.

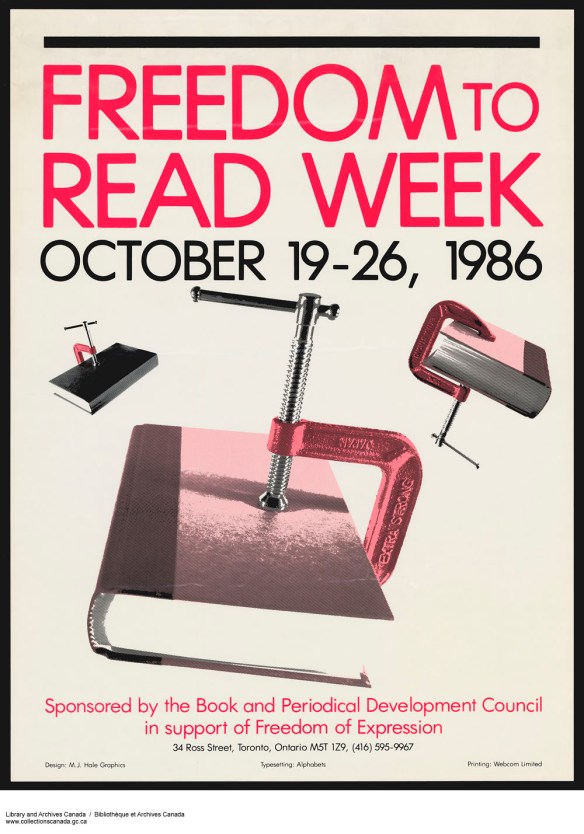

However, one need not look to fictional realms or even historical accounts to grasp the importance of this issue. Established in 1984, Freedom to Read Week is an annual campaign that sheds light on the covert nature of censorship, raising awareness about the challenges faced by publication and library programs within our very own communities.

Did you know that even seemingly banal works such as The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm and Bambi have been challenged internationally? The history of censorship and challenges to books and other publications is long and varied both here in Canada and abroad. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) plays a unique role amongst Canadian libraries, preserving copies of all books published in Canada—including audio and electronic formats—to ensure these stories remain accessible for future generations.

Read on to learn about key themes in Freedom to Read Week’s history and how they relate to LAC’s mandate and involvement in the campaign.

Access copies of books and other publications preserved at Library and Archives Canada. Photograph: Rebecca Murray, Library and Archives Canada.

School libraries

Classrooms and school libraries are often subject to book challenges due to wide-sweeping policies and book-specific complaints. Since the inception of Freedom to Read Week, numerous challenges in school settings have been documented with responses ranging from training teachers on how to address sensitive topics in literature, to stopping the removal of books from libraries to board meetings drawing hundreds of attendees and, in extreme cases, even book burnings.

National library collections, like the one at LAC, differ from public and school libraries in that they are non-circulating (outside of our reading rooms) and not influenced by public demand or policy changes. As a result, the removal of books from other libraries or schools does not affect the holdings at LAC.

Works about censorship

From the earliest days of Freedom to Read Week to now, writers and thinkers have explored the topic of censorship in Canada, examining its impact across literature, libraries, cinema, and beyond. These important works allow us to trace the history of censorship and publication bans in Canada, offering valuable perspectives on how these issues have evolved over time.

Examples in LAC’s published holdings include Dictionnaire de la censure au Québec: Littérature et cinéma (2006), by Pierre Hébert, Kenneth Landry and Yves Lever; Fear of Words: Censorship and the Public Libraries of Canada (1995), by Alvin Schrader; and Women Against Censorship (1985), by Varda Burstyn.

Dictionnaire de la censure au Québec: Littérature et cinéma (2006), by Pierre Hébert, Kenneth Landry and Yves Lever; Fear of Words: Censorship and the Public Libraries of Canada (1995), by Alvin Schrader; and Women Against Censorship (1985), by Varda Burstyn.

Photograph: Rebecca Murray, Library and Archives Canada.

Shifting trends

When we think of classic fairy tales and stories like Bambi, it might be hard to imagine how anyone could find fault with them. Yet, as our society evolves, so do our perceptions of what is considered offensive or appropriate. Ideas about acceptable content are always shifting, and this is evident in various policies and debates: from decisions on whether to include graphic novels (often referred to as comic books) in public libraries, to petitions seeking to revoke awards from past literary winners, to the regulations on importing and selling certain publications in Canada. These changes are part of a broader historical trend that will undoubtedly continue. By examining data on content challenges reported by librarians on the front lines, we can observe how these societal attitudes evolve over time.

You can read all about Freedom to Read Week’s history in Canada and find out about other challenged titles on the campaign’s website.

The 41st edition of Freedom to Read Week will take place from February 23rd to March 1st, 2025. Stay up to date on the campaign and related events.

Rebecca Murray is a Literary Programs Advisor in the Outreach and Engagement Branch at Library and Archives Canada.