By Andrew Horrall

Bellenden Seymour Hutcheson

Bellenden Seymour Hutcheson was born at Mount Carmel, Illinois, on December 16, 1883. He studied medicine at Northwestern University near Chicago and worked as a doctor. Hutcheson was physically striking—he had white hair and piercing blue eyes. Like many Americans, Hutcheson decided to fight for Canada. On November 6, 1915, he joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps at Hamilton, Ontario, and was assigned to the 75th Battalion.

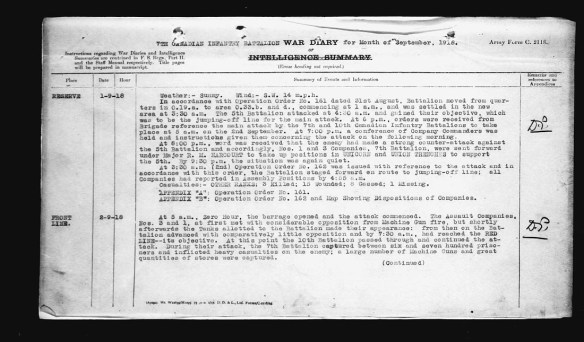

On September 2, 1918, near Cagnicourt, France, Hutcheson advanced into open ground with his battalion and “without hesitation and with utter disregard of personal safety he remained on the field until every wounded man had been attended to. He dressed the wounds of a seriously wounded officer under terrific machine-gun and shellfire, and, with the assistance of prisoners and of his own men, succeeded in evacuating him to safety, despite the fact that the bearer party suffered heavy casualties. Immediately afterwards he rushed forward, in full view of the enemy, under heavy machine-gun and rifle fire, to tend a wounded sergeant, and, having placed him in a shell-hole, dressed his wounds.” (London Gazette, no. 31067, December 14, 1918)

For his bravery in another action, Hutcheson received the Military Cross.

Dr. Hutcheson married a woman from Nova Scotia at the end of the war and returned to his medical practice in Illinois. He visited Canada regularly over the years, and took part in battalion reunions, but he rarely spoke about his wartime experiences. He died in Cairo, Illinois, on April 9, 1954. His Victoria Cross is held by the Toronto Scottish Regiment Museum.

Sources

“VC from Illinois modestly declines to details exploits,” The Globe and Mail, March 6, 1930, p. 13.

“‘Six-bits’ reunion is first since war,” The Globe and Mail, April 13, 1931, p. 14.

Arthur George Knight

Arthur George Knight was born at Haywards Heath, England, on June 26, 1886. In 1911, he immigrated to Canada and worked as a carpenter. He joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force in December 1914 and served with the 10th Battalion. He was awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre in November 1917.

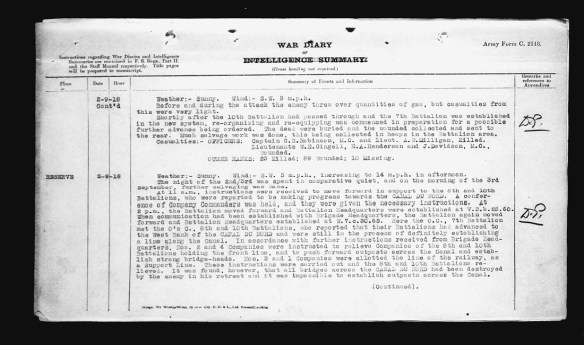

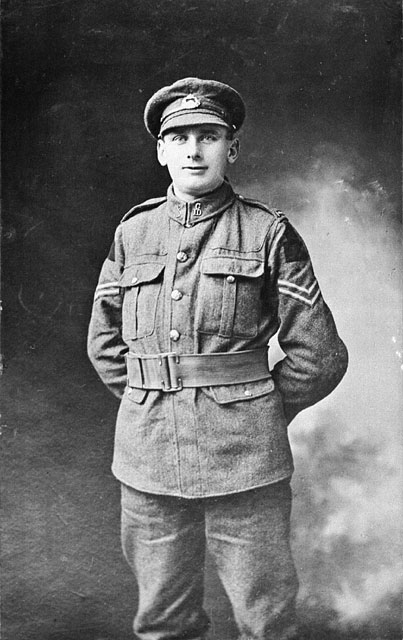

Sergeant A.G. Knight, VC, undated (a006724)

On September 2, 1918, near Cagnicourt, France, Knight “led a bombing section forward under heavy fire and engaged the enemy at close quarters. Seeing that his party continued to be held up, he dashed forward alone, bayoneting several of the enemy machine-gunners and trench mortar crews, and forcing the remainder to retire in confusion.” As Knight’s platoon chased the retreating Germans, he “saw a party of about thirty of the enemy go into a deep tunnel which led off the trench. He again dashed forward alone, and, having killed one officer and two NCOs, captured twenty other ranks. Subsequently he routed, single-handed, another enemy party which was opposing the advance of his platoon.” (London Gazette, no.31012, November 15, 1918)

Knight was badly wounded in this fighting and died the following day. His Victoria Cross is held by Calgary’s Glenbow Museum.

William Henry Metcalf

Lieutenant-Corporal W. H. Metcalf, VC, undated photograph (a006727)

William Henry Metcalf was born in Waite Township, Maine, on January 29, 1885. He worked as a barber before travelling to Fredericton, New Brunswick, to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force on August 15, 1914. He served as a signaler with the 16th Battalion. Metcalf was awarded the Military Medal for his actions in September 1916 at the Battle of the Somme when he volunteered to provide medical assistance to a severely wounded comrade in no man’s land. Having saved the man’s life, Metcalf then repeatedly exposed himself to heavy shelling in order to repair telephone wires. His medal citation notes that “during twenty months of service in the field his conduct has been one of uniform bravery and cheerful devotion to duty.” (London Gazette, no. 29893, January 6, 1917)

Metcalf was awarded the Military Medal for a second time for his actions on August 8, 1918, during the Battle of Amiens. He laid telephone wire across no man’s land during the initial attacks and remained all day under intense shell fire, ensuring that the wire was not damaged. (London Gazette no. 31142, January 24, 1919)

Metcalf was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions on September 2, 1918, near Cagnicourt, France. When his battalion’s advance began to falter, Metcalf “rushed forward under intense machine-gun fire to a passing tank on the left. With his signal flag he walked in front of the tank, directing it along the [German] trench in a perfect hail of bullets and bombs. The machine-gun strong points were overcome, very heavy casualties were inflicted on the enemy, and a very critical situation was relieved.” (London Gazette, no. 31012, November 15, 1918)

Metcalf died at Lewiston, Maine, on August 8, 1968. His Victoria Cross is held by the Canadian Scottish Museum, Victoria, BC.

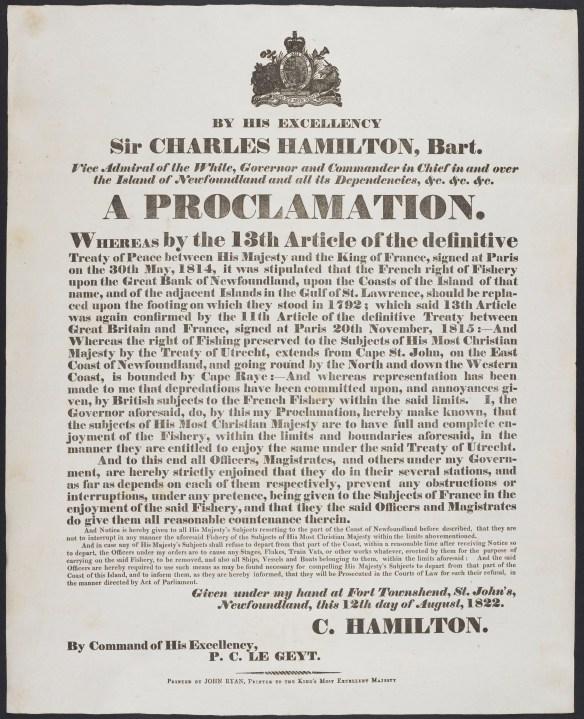

Cyrus Wesley Peck

Cyrus Wesley Peck was born at Hopewell Hill, New Brunswick, on April 26, 1871. He trained to be a soldier, but was unsuccessful in taking part in the South African War. At the start of the First World War, Peck was managing a salmon cannery in British Columbia and serving in the militia. He enlisted in the 30th Battalion on November 8, 1914, at the rank of Major. In late 1916, Peck was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and given command of the 16th Battalion, the Canadian Scottish Regiment.

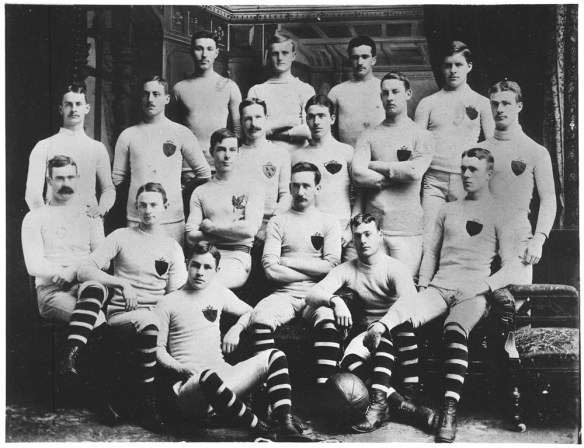

Lieutenant-Colonel Cyrus W. Peck, VC, DSO, 16th Battalion, leaving Buckingham Palace (a006720)

Peck received the Distinguished Service Order, was mentioned in dispatches five times, and was wounded twice. He was also elected to the House of Commons for the riding of Skeena, British Columbia, in the federal election of December 1917. This so-called “Khaki Election” was the first one in which soldiers on active service were allowed to vote. Though Peck was now a Member of Parliament, he continued to carry out his military duties in France.

Peck is Canada’s unlikeliest Victoria Cross hero. Though his walrus moustache gave him a military look, he was 47 years old, 5 feet and 9 inches tall, and a portly 250 pounds. Nonetheless, on September 2, 1918, near Cagnicourt, France, Peck saw that his battalion’s advance had stalled. So he “made a personal reconnaissance under heavy machine-gun and sniping fire, across a stretch of ground which was heavily swept by fire. Having reconnoitered the position he returned, reorganised his battalion, and, acting upon the knowledge personally gained, pushed them forward and arranged to protect his flanks. He then went out under the most intense artillery and machine-gun fire, intercepted the tanks, gave them the necessary directions, pointing out where they were to make for, and thus pave[d] the way for a Canadian Infantry battalion to push forward. To this battalion he subsequently gave requisite support. His magnificent display of courage and fine qualities of leadership enabled the advance to be continued, although always under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire, and contributed largely to the success of the brigade attack.” (London Gazette no. 31012, November 15, 1918)

Peck lost his seat in the House of Commons in the 1921 federal election. He sat in British Columbia’s provincial legislature from 1924 to 1933, and died at Sydney, British Columbia, on September 27, 1956. His Victoria Cross is held by the Canadian War Museum.

Sources

“Won VC in 1918 while a member of parliament,” The Globe and Mail, September 28, 1956, p. 7.

John Francis Young

John Francis Young was born in Kidderminster, England, on January 14, 1893, and immigrated to Canada sometime before the war. He enlisted in the 87th Battalion at Montreal on October 20, 1915, and served as a stretcher bearer. Young was wounded at the Somme in November 1916.

Young was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions on September 2, 1918, near Dury, France. When German artillery and machine guns cut down Young’s company, he spent over an hour treating wounded comrades in full view of the enemy. He repeatedly travelled back to the Canadian lines for more medical supplies, but always returned to the wounded men. Young then organized the stretcher bearers who carried the wounded men to safety. (London Gazette no. 31067, December 14, 1918)

Young was gassed in a subsequent battle and suffered permanent and debilitating lung damage. He died at Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, Quebec, on November 7, 1929. His Victoria Cross is held by the Canadian War Museum.

Sources

“John F. Young, VC, is dead in Quebec,” The Globe and Mail, November 8, 1929, p. 1.

Library and Archives Canada holds the service files for Bellenden Seymour Hutcheson, Arthur George Knight, William Henry Metcalf, Cyrus Wesley Peck and John Francis Young.

Andrew Horrall is a senior archivist in the Private Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada.