In 1894, the Canadian government’s interest turned towards the Yukon. There were concerns about the influx of American citizens into the region as the new border was disputed in certain areas. In addition, there were mounting concerns over law and order, and the liquor trade among the resident miners.

Inspector Charles Constantine of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) was dispatched to the Yukon to carry out law enforcement, border and tariff control, and to assess the policing needs of the territory. After four weeks of duty, Constantine returned south and submitted his report to the government recommending that a larger force of seasoned, robust and non-drinking constables between the ages of 22 and 32 years be sent to the Yukon to carry out border and law enforcement. It wasn’t until 1895 that a contingent of 20 constables under Inspector Constantine’s command finally set out from Regina towards the Alaskan border. They reached the town of Forty Mile and established Fort Constantine in July 1895. The year was marked by logging, enduring the elements and insects, and constructing their detachment building. Remarkably, crime during this time was rare.

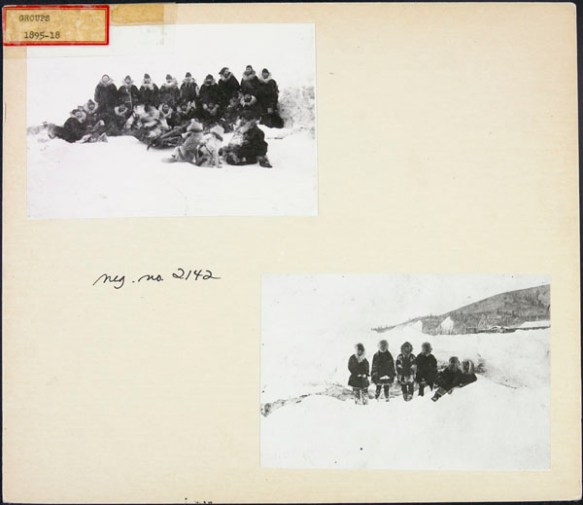

Fort Constantine detachment (now Forty Mile) on the Yukon River, 1895, the first North West Mounted Police group in the Yukon (MIKAN 3715394)

Things changed drastically in 1896. Gold was discovered near the Klondike River and news spread quickly. From a population of about 1,600 in the area, it swelled by tens of thousands by the summer of 1897 with prospectors, gamblers, speculators and those with criminal intent. A majority of these miners came from the United States. The NWMP commanded by Inspector Charles Constantine faced a challenge in policing the influx of miners streaming into the region from all directions. Customs posts were set up at the Chilkoot and White Pass summits and the collection of duties and tariffs began. Those miners with insufficient provisions to make it to Dawson City and survive the winter were turned back. By 1898, outnumbered, under-supplied and under-staffed, 51 NWMP members and 50 members of the Canadian militia maintained Canada’s sovereignty, and law and order at the border passes and in the mining areas in the Yukon.

North West Mounted Police in the Yukon, 1898–1899 (MIKAN 3379433)

The Klondike gold rush lasted into 1899 until gold was discovered in Alaska. The migration of fortune seekers turned their attention and travelled towards that state’s Nome region. However, the Klondike gold rush left an infrastructure of supply, support and governance that led to the continued development of the territory to such a great extent that the Yukon was made into a Canadian territory on June 13, 1898. The North West Mounted Police also stayed to maintain peace and order under their steady hands.

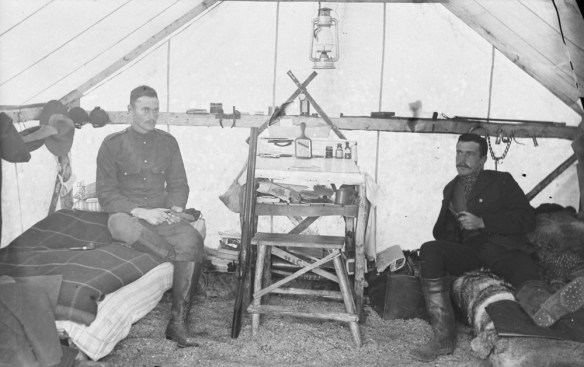

North West Mounted Police in the Yukon, 1898–1910 (MIKAN 3407658)

A wide variety of documentation is available at Library and Archives Canada (LAC) related to the North West Mounted Police, the Klondike gold rush, and their time in the territory. You may start your initial research in Charles Constantine‘s fond using Archives Search. A general search using his name will provide further records from the Department of Justice.

Try searching with some of these keywords to get more records from the era:

Bennett Lake / Lake Bennett

Chilkoot Pass

Dawson City Yukon

Dyea

Forty Mile

Gold rush

Klondike River

Skagway

White Pass

Yukon River