By Caitlin Webster

British Columbia joined Canada 150 years ago, and in the years that followed, federal infrastructure expanded throughout the province. This infrastructure is well documented throughout Library and Archives Canada’s collections. This eight part blog series highlights some of those buildings, services and programs, as well as their impact on B.C.’s many distinct regions.

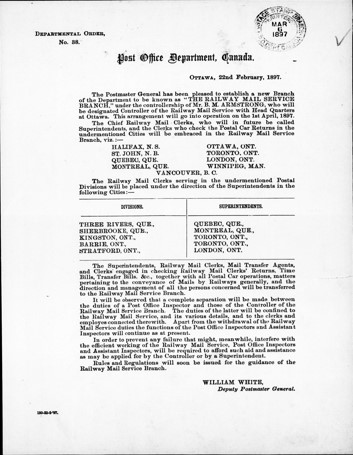

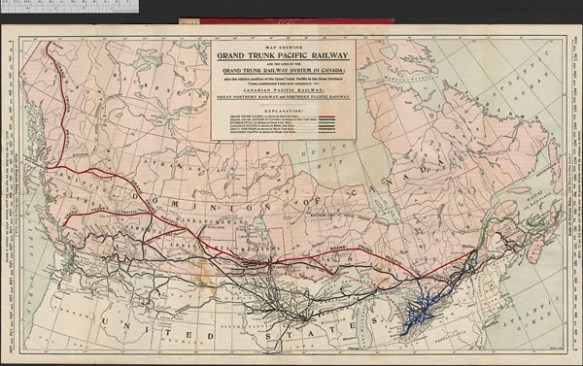

As British Columbia negotiated its terms for joining Confederation, one of the conditions included the establishment of a telegraphic service. Canada’s Dominion (or Government) Telegraph Service, which formed part of the Department of Public Works, was responsible for providing this. It operated telegraph lines in remote areas not covered by railway telegraph systems or private firms. In B.C., the federal government operated lines in the south and on Vancouver Island, and as it expanded its presence in northern B.C. and Yukon in the 1890s, work began on the Yukon Telegraph Line.

In 1899, the Privy Council Office approved the construction of a telegraph line between Dawson City in what is now Yukon and Bennett, B.C. Now a ghost town, Bennett was once a thriving centre for the Klondike Gold Rush.

Soon after the line to Bennett was completed, work began on a branch line to Atlin, and then an extension from Atlin to the transcontinental line at Quesnel. This work finished in 1901, although the construction of various branch lines continued over the next decade. As the construction work progressed, the Department of Public Works built telegraph offices and stations at regular intervals along the line. Stations in towns and settlements often housed other federal government services such as post offices and customs houses. Operators at these stations worked regular business hours and enabled customers to send and receive telegrams.

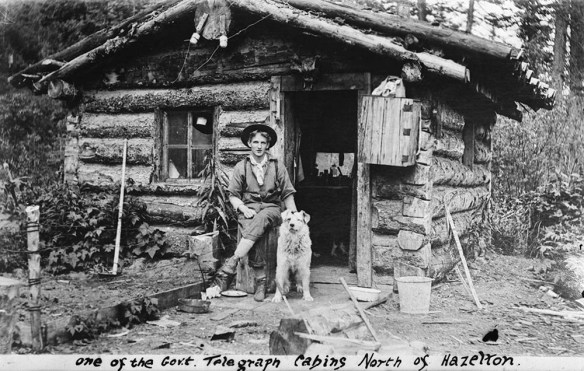

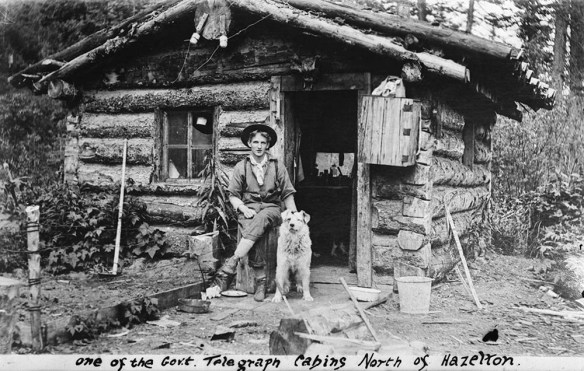

To help ensure that the line had sufficient voltage to carry telegraph messages between the stations, crews also constructed intermediate battery stations, also known as repeater stations, along the more remote sections of the line. At first, these “bush stations” were simple one-room cabins, housing both the assigned operator and the lineman. As these sites rarely saw customers requesting telegrams, both operators and linemen undertook the difficult work of keeping the telegraph wires in good order. In the summer of 1905, crews built second cabins at these isolated stations to ease some of the difficulties of living in such close quarters.

One of the government telegraph cabins [Dominion Government Telegraph cabin, North of Hazelton; telegraph operator Jack Wrathall and dog sit in front of the cabin] (a095734-v8)

Even smaller were the refuge cabins, where linemen could stay overnight if caught in bad weather while maintaining the line. Spaced approximately 10 miles (16 kilometres) apart, these small 8 x 10-foot (2.4 by 3 metres) cabins contained a stove, bunk and limited food supplies.

The telegraph lines affected local First Nations, ranging from the Lhtako Dene, Nazko, Lhoosk’uz Dene and ?Esdilagh Nations near Quesnel to the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in Atlin. Early work on telegraph lines in the 19th century often proceeded without consultation or agreements with First Nations, which led to confrontations when work crews trespassed on their land. A number of First Nations made use of materials left from earlier abandoned telegraph lines, using the wire on bridges and traps. Some First Nations men worked on the telegraph lines, serving as construction workers, linemen and pack-train operators. The most famous among them was Simon Peter Gunanoot, who helped to construct the line and later worked delivering provisions to the bush stations. Accused of murder in 1906, he evaded searchers for 13 years before turning himself in. At his trial in 1919, a jury acquitted him in a mere 15 minutes, and his remarkable story has since inspired books, documentaries and short films.

By the 1920s and 1930s, the federal government began replacing telegraph lines with radio and telephone communications. At the same time, interest in the line as a trail for adventure hiking grew. While the federal government sold off or abandoned the last portions of the Yukon Telegraph Line by 1951, parts of the line are still used by guide outfitters today.

To learn more about the Yukon Telegraph Line, check out the following resources:

- “A socio-cultural case study of the Canadian Government’s telegraph service in western Canada, 1870–1904,” John Rowlandson thesis, 1991 (OCLC 721242422)

- Wires in the Wilderness: The Story of the Yukon Telegraph, Bill Miller, 2004 (OCLC 54500962)

- Pinkerton’s and the Hunt for Simon Gunanoot: Double Murder, Secret Agents and an Elusive Outlaw, Geoff Mynett, 2021 (OCLC 1224118570)

Caitlin Webster is a senior archivist in the Reference Services Division at the Vancouver office of Library and Archives Canada.