This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

By Jasmine Charette

In a previous blog post, “Enfranchisement of First Nations Peoples,” I discussed the history and impact of enfranchisement on First Nation communities. This blog post explains how to search for enfranchisement records.

Some parts of your search may require an on-site visit. If you are unable to visit us, you can hire a freelance researcher or request assistance from Reference Services through our Ask Us a Question form. Please note that our research services are limited.

Collections Search

The simplest way to find enfranchisement records is through Collections Search. You can do this if you know the individual’s name at the time, the approximate year of enfranchisement and their band. Sometimes, instead of the band, records will name the agency or district that administered the band at the time.

If you are unsure which agency or district administered the band, you can check these finding aids to identify this information. Sorted by region, the finding aids list agencies, districts and superintendencies, noting which bands were under their administration, the years of responsibility, and allows for tracing administration over time. These guides are available in our Reference Room and are all part of RG10 (Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds).

- 10-202: British Columbia

- 10-12: Western Canada (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon and Northwest Territories)

- 10-157: Ontario

- 10-249: Quebec

- 10-475: The Maritimes (Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Newfoundland from 1984)

- 10-145: Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia had a different system than the rest of Canada)

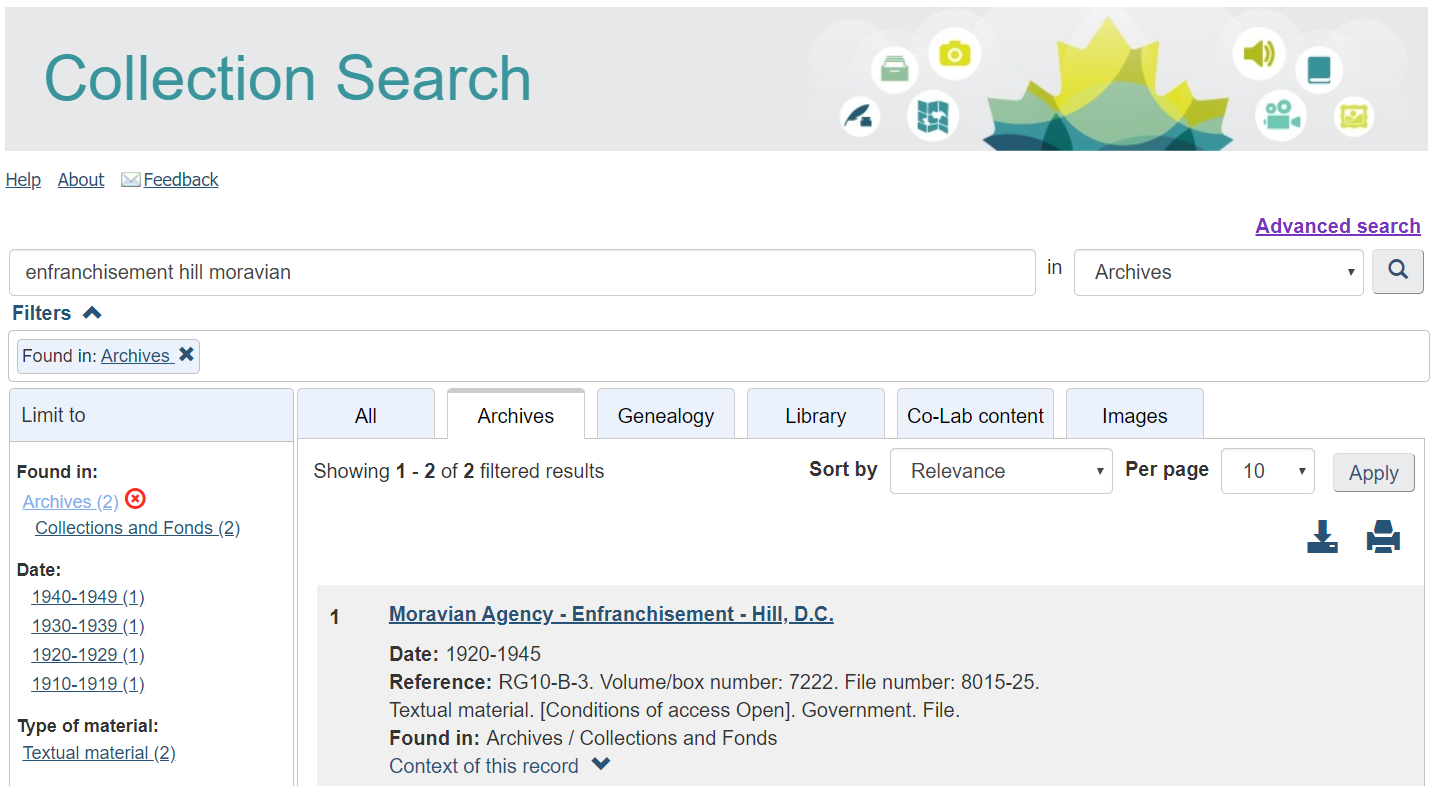

Here’s how to search for enfranchisement records with the Collections Search database.

- Under the “Search the Collection” menu of the LAC website, click Collection Search.

- In the search bar, search for “enfranchisement [NAME] [BAND/AGENCY].”

- In the drop-down menu, change “All” to “Archives.”

- Click the magnifying glass.

- Browse the results and select the one for the individual you are searching for.

A complete reference for a record will look something like this:

RG10-B-3, vol. 7222, file number 8015-25, title “Moravian Agency – Enfranchisement – Hill, D.C.”

Please note that the enfranchisement records you identify may be restricted and require an access request under the Access to Information or Privacy acts. For more information on these requests, please consult our site.

Orders-in-Council

Another way to search for enfranchisement records is by searching Orders-in-Council (OICs). This is because enfranchisement was confirmed through OICs. While the OICs themselves do not include the main enfranchisement documents, they can provide the following information.

- Whether or not someone was enfranchised

- The band they were enfranchised from

- Their name at enfranchisement

- Whether or not the enfranchisement was due to marriage

With this information you may find more records in Collection Search.

OICs are indexed by year in our Red Registers, red books in our Reference Room. The registers are split into two parts. The first part lists OICs by number (which are loosely sorted by date), the second part lists keywords to help find specific OICs. Prior to the 1920s, people were mentioned individually in our Red Registers. An external tool can help you find individuals and families in later OICs—the Order In Council Lists website has an index with names of enfranchised people up to 1968.

For specific information on how to search OICs, please consult our previous blog posts “Orders-in-Council: What You Can Access Online” and “How to find Privy Council Orders at Library and Archives Canada.”

If you have any questions, are unable to identify an individual, or need assistance with navigating our holdings, please do not hesitate to contact Reference Services! We are always happy to help.

Jasmine Charette is a reference archivist in the Reference Services Division of the Public Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)