In my last blog post, I talked about how important user experience (UX) feedback was to the development and improvement of Library and Archives Canada’s (LAC) new website design. I also mentioned that we would be taking an iterative approach, continuing to evolve in response to the feedback received. Now that it’s been nearly a year since the launch, this is a great time to give you a little behind-the-scenes look about how we handle analytics and feedback, and share some details on the changes (big and small) that we’ve made and are looking to make on the website.

Analytics

Web analytics, such as the number of visits and visitors, and the average time on the site, are all helpful measures when it comes to determining the success of a website. They can tell us which pages are used most frequently and give us a sense of what our users are searching for on the site. Some more advanced features, like flows, can even show us how people navigate our website. Here is one example of a healthy flow for our “Help with your research” page, captured in January 2023.

The centre column is the page under analysis, in this case “Help with your research.” On the left is where people were before arriving at “Help with your research,” and on the right is where they went after leaving that page. For example, the top lines show people navigating from the home page to “Help with your research” to “Genealogy and family history.” This is exactly what we want to see: individuals going to their specific subject of interest. And we are also pleased that only a small number, the tiny bit of red at the bottom right in the centre, are leaving the site altogether from the help page.

Feedback

In addition to analytics, we collect users’ online experience feedback using different channels. If you’ve ever scrolled all the way down to the bottom of our web pages, you may have noticed a little box that looks like this.

The feedback collection tool (Library and Archives Canada)

This box is called a feedback collection tool. It provides an easy, anonymous way for our users to provide us with comments about their experiences, both positive and negative. We also get a lot of feedback through our email (servicesweb-webservices@bac-lac.gc.ca), as well as through other teams like Reference Services. Our top task survey, which is the little pop-up that some of you see when you log onto the site, is another tool that is available for users to provide comments.

All of this feedback is gathered together in a single location and then analyzed. We read every single comment that you send, and we look for common problems that people encounter.

Small changes, big results

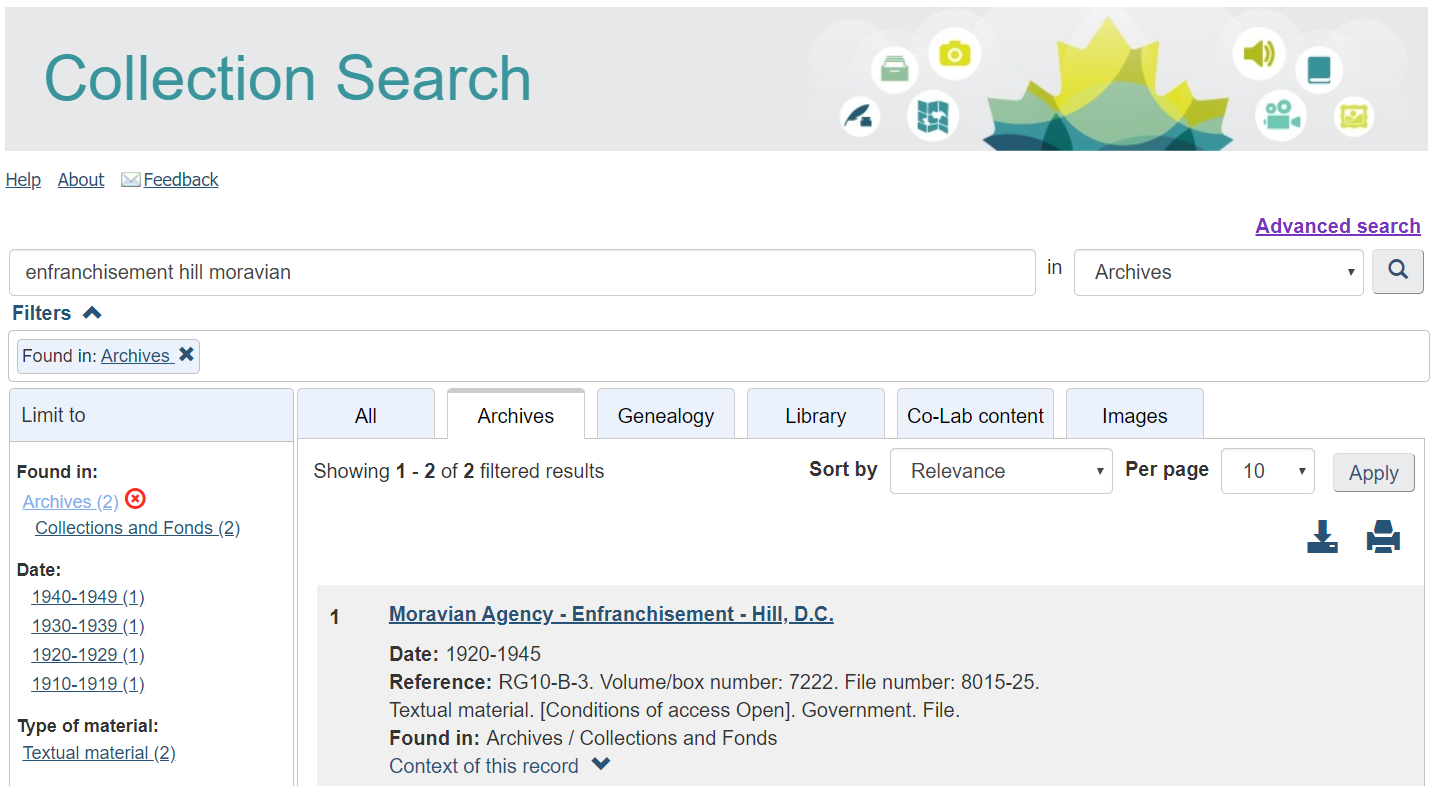

As fascinating as this information is in its own right, we are using it to make improvements across the site. Our iterative approach means we make small changes on a regular basis in response to feedback. For example, when the website was launched in August 2022, we noticed that a lot of people were using the Collection Search bar on the home page to access some of our stand-alone databases. This means that it was unclear to users what they could search and access from the Collection Search bar. This is what it originally looked like.

To help users with their searches and navigate our website, we worked to make it more obvious what the search bar was for, how to use it and how to find other helpful resources. Here are some of the options that we considered.

Ultimately, we combined several different features and arrived at this version.

The final version of the Collection Search bar (Library and Archives Canada)

And it worked! Since then, the number of searches for databases through Collection Search bar dropped down to zero. Success!

UX Research and Design

Another tool in our toolbox is UX research and design. A few months ago, one of our UX designers, Alexandra Haggert, explained how UX design works. Here is another example of how using metrics and feedback, coupled with UX research and design, can improve our website for a better user experience.

When we launched Census Search beta in November 2022, feedback from users pointed out two common problem areas. Firstly, when searching, users would like to have the ability to search several specific provinces, rather than all or one at a time. Secondly, when searching in genealogy, often the “Year of birth” or “Year of immigration” might be an estimate. Here is what the page looked like before.

To better help users in their searches, we came up with the solution of adding two features. The first was the ability to select one or more provinces by check box. The second was the ability to a range for the year of birth or immigration allowing to search up to 10 years before and after the date identified.

The final version of Census Search (Library and Archives Canada)

This made it much easier for our users to find specific individuals using Census Search.

If you want to provide feedback on Census Search, you can email recherchecollectionsqr-collectionsearchqa@bac-lac.gc.ca.

What are we working on now?

Some of the most common comments that we are getting are related to the following:

- What is or isn’t available at LAC, especially in terms of modern records

- How to access obituaries on the LAC website

- How to find some of our smaller databases (like Second World War Service Files – War Dead, 1939 to 1947)

We are still working on the best solutions to these issues, so stay tuned.

And this is just the beginning! Analytics, feedback, and UX research and design will continue to be essential tools when it comes to website design. They help us to know what you want and need so that we can improve your online experience. So please keep the feedback coming! Reach out to us at servicesweb-webservices@bac-lac.gc.ca.

Andrea Eidinger is an acting Manager in Web, part of the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)