By Rebecca Murray

A few months ago, I stumbled upon something unexpected while digging through the archival database of the Office of the Chief Press Censor. Established by Order in Council on June 10, 1915, this office had sweeping authority to oversee the censorship of printed materials during wartime. It was authorized by the Secretary of State to “appoint a person to be censor of writings, copy or matter printed or the publications issued at any printing house.” Naturally, I was interested. I began to review the series of documents from 1915 to 1920 found within the Secretary of State fonds (RG6/R174). These records mostly pertain to censorship restrictions during the First World War, covering everything from subversive elements in Canada to war propaganda.

With over 1,500 file-level descriptions, the series details a variety of publications flagged by the Press Censor. Unsurprisingly, most of the materials under scrutiny were related to the war: German-language publications, pro-German writings, and other sensitive information. But a file on Valentine’s Day cards? Maybe they were too racy, I thought to myself.

Curious, I opened the file (available on digitized microfilm at Canadiana by Canadian Research Knowledge Network). The correspondence between the Deputy Postmaster General R.M. Coulter, Chief Press Censor Lt. Col. E.J. Chambers, and the Department of Justice began in mid-January 1916. The offending item in question was a Valentine’s Day card and envelope produced by the Volland Company of Chicago.

The Valentine’s day card in question, published with censor markings. Source: RG6 volume 538 file 254, microfilm reel T-76, page 655.

The main issue? Deputy Postmaster General Coulter flagged the card on January 18, 1916, to Chief Press Censor Chambers, complaining that the label on the envelope and the facsimile of a rubber stamp on the card resembled official censorship markings. His concern was that these could “mislead the Officials of the Government.” Unfortunately, the file does not include a copy of the censored envelope.

Chambers responded the very next day, agreeing with Coulter: “I certainly think that it would be a grave mistake to allow these particular envelopes to gain general circulation in Canada, for they would not only attract unnecessary attention to the censorship, but might prove a stumbling block in the event of it being found necessary to apply a general censorship to the mails later.”

The issue continued to escalate with a memorandum sent to the Deputy Minister of Justice on January 20, followed by a letter dated January 21 explaining that “it would be most injudicious at the present time to permit Valentines and envelopes such as those referred to me, to be circulated in Canada.”

The same letter also sheds light on the broader role of the Office of the Chief Press Censor: “I might explain confidentially, that one of the main objects sought to be accomplished by Censorship in Canada at the present time, is to intercept enemy correspondence passing to and from Teuton Agents and sympathisers in Canada and Intelligence Officers of the enemy Governments in either enemy countries or neutral ones. Consequently, it is the established practice of the censorship to endeavor to conduct its operations with as little publicity as possible, it being felt that to advertise the fact that there is an active censorship system in Canada is but to defeat the object explained in the preceeding.”

Although the Valentine’s Day card in question was not labelled as “enemy correspondence,” its use of what appeared to be censor markings drew significant concern from both the Postmaster General and the Chief Press Censor. During a time when censorship was highly active but intentionally discreet, they were particularly wary of anything that might expose or ridicule their work.

Something that struck me in the latter part of the file was a series of notes exchanged between regional censor officials and booksellers, along with other vendors who had ordered or purchased the card. In response to government letters, several vendors replied promptly, assuring they would return the cards to the American publisher. However, it’s unclear how many cards were already in circulation or if any had been sold before the recall.

Letter to Chief Press Censor Chambers from the Regional Press Censor’s office in Western Canada. Source: RG6 volume 538 file 254, microfilm reel T-76, page 674.

In addition to the intergovernmental correspondence, the Chief Press Censor reached out to the publisher in a letter dated January 25, noting that the Canadian authorities wished to avoid letting the war interfere with trade and relations between Canada and the United States: “The sincere desire of the Canadian Authorities is to prevent as far as possible, the war from interfering with the trade and other relations existing between Canada and our good neighbours to the South.” Despite the firm stance, the Chief Press Censor’s diplomatic tone reflected a desire to manage the situation tactfully.

Letter from P.F. Volland & Co to Chief Press Censor for Canada. Source: RG6 volume 538 file 254, microfilm reel T-76, page 669.

A response letter from the publisher to the Press Censor dated January 24, sheds light on their reaction to the product’s removal from the Canadian market. Regardless of the original intent behind the censor markings, the publisher assured the Chief Press Censor that “it was not our intention to direct attention in any undesirable way to the censorship at present in force in the Dominion.”

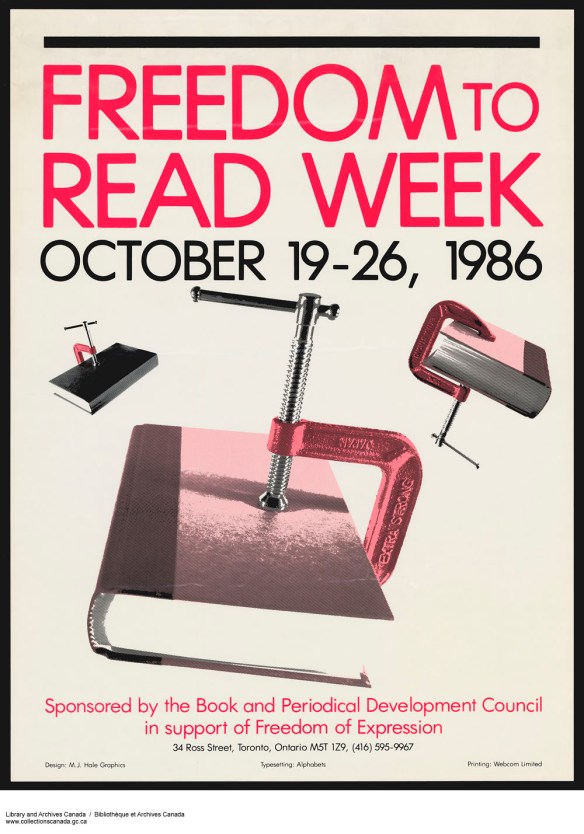

The work of the Chief Press Censor during the First World War highlights the government’s influence over the flow of information during the conflict. While this particular case may seem benign—more likely to amuse than alarm us today—it serves as a reminder that censorship, in various forms, remains an ongoing issue. To learn more, explore Library and Archives Canada’s role in Freedom to Read Week, an annual campaign that raises awareness of censorship and book challenges across Canada.

Rebecca Murray is a Literary Programs Advisor in the Outreach and Engagement Branch at Library and Archives Canada.