By Forrest Pass

February 15, 2025, is the sixtieth birthday of the National Flag of Canada. The media and heritage institutions—including Library and Archives Canada—often mark the flag’s anniversary by sharing some of the “also-rans,” a selection of Canadians’ design submissions in the months and years leading up to the flag’s adoption.

It’s fun to speculate about alternative designs: for example, what would the Canadian Olympic teams’ uniforms look like if we had selected a flag other than the now-iconic red-and-white maple leaf design? What’s more, these rejected designs tell us something about their creators’ values and their ideas about the country’s past, present and future.

Flag enthusiasts often have our favourite “also-rans.” The story of my favourite runner-up brings together two mid-February fixtures: flags and chocolates.

In 2013, while working as a historian at the Canadian Museum of History, I found a set of ten small fabric flags for sale on eBay that appeared to date from the Great Flag Debate. The seller, sadly, knew nothing about their origins, having bought them as part of a trunk load of miscellaneous bric-a-brac at an estate sale. However, these little flags were noteworthy to me because so few proposed designs made it off the drawing board; it took a rare confidence in one’s own design—and a little bit of disposable income—to produce fabric examples for distribution.

A mysterious Canadian flag proposal. (Canadian Museum of History, 2013.47.1)

I could confirm that the proposal had been submitted to the House of Commons flag committee because it hangs, alongside many others, on the wall of the committee’s meeting room in a 1964 press photo. This was enough to justify the flags’ acquisition for the museum’s collection, but I still hoped to identify the designer and the flags’ intended symbolism.

Members of the House of Commons Flag Committee surrounded by 1200 designs for a new Canadian flag, October 7, 1964. The mystery flag is circled in red. (Library and Archives Canada, a213164)

As luck would have it, a colleague came across a reference to this very flag four years later in the Hansard record of the Great Flag Debate. In a speech on August 26, 1964, Clément Vincent—MP for Nicolet-Yamaska, Quebec—had described both the flag and its symbolism to his fellow parliamentarians. A little more digging in Hansard, and I had the name of the designer: Jean Dubuc. And after some Internet sleuthing, I uncovered a letter to a newspaper, an obituary and a Facebook profile. I was soon corresponding with the designer’s son, Daniel Dubuc, who told me more of his father’s story.

Jean Dubuc (1920–1965) was born in Chandler, Quebec, and grew up in Chicoutimi, where his grandfather was a pulp-and-paper and hydroelectricity magnate. He joined the Quebec public service in 1951 and settled in the Québec City suburb of Sainte-Foy. A lifelong heraldry enthusiast, he conceived his proposed Canadian flag in the late 1950s. In 1959, he sent a copy of it to every senator and member of the House of Commons. He included a printed bilingual cover letter, and his son generously donated a copy to the museum.

Among the thousands of designs submitted before and during the Great Flag Debate, Dubuc’s stands out. For one, he cleverly intertwined the red cross of St. George on a white background, the traditional flag of England, with the pre-revolutionary French merchant ensign, a white cross on a blue background. Thus, the Dubuc flag evoked gave equal status to the two principal settler communities without using the more familiar—and sometimes controversial—Union Jack and fleur-de-lys.

A second intriguing feature was Dubuc’s inclusion of Indigenous people in his flag design, at a time when most designs, including the one finally selected, included no such reference. The white field of the flag, wrote Dubuc, represented “the first occupants of the land,” the First Nations and Inuit, “still in possession of vast expanses of snow and ice of this country.” This comment put Dubuc ahead of his time: even the few mid-century amateur designers who did include Indigenous symbolism rarely acknowledged that Indigenous people were still around, much less that they still owned and occupied these lands. (Dubuc did not mention the third constitutionally recognized Indigenous group in Canada today, the Métis Nation, whose history and continued existence were less well known in the 1950s, particularly in eastern Canada.)

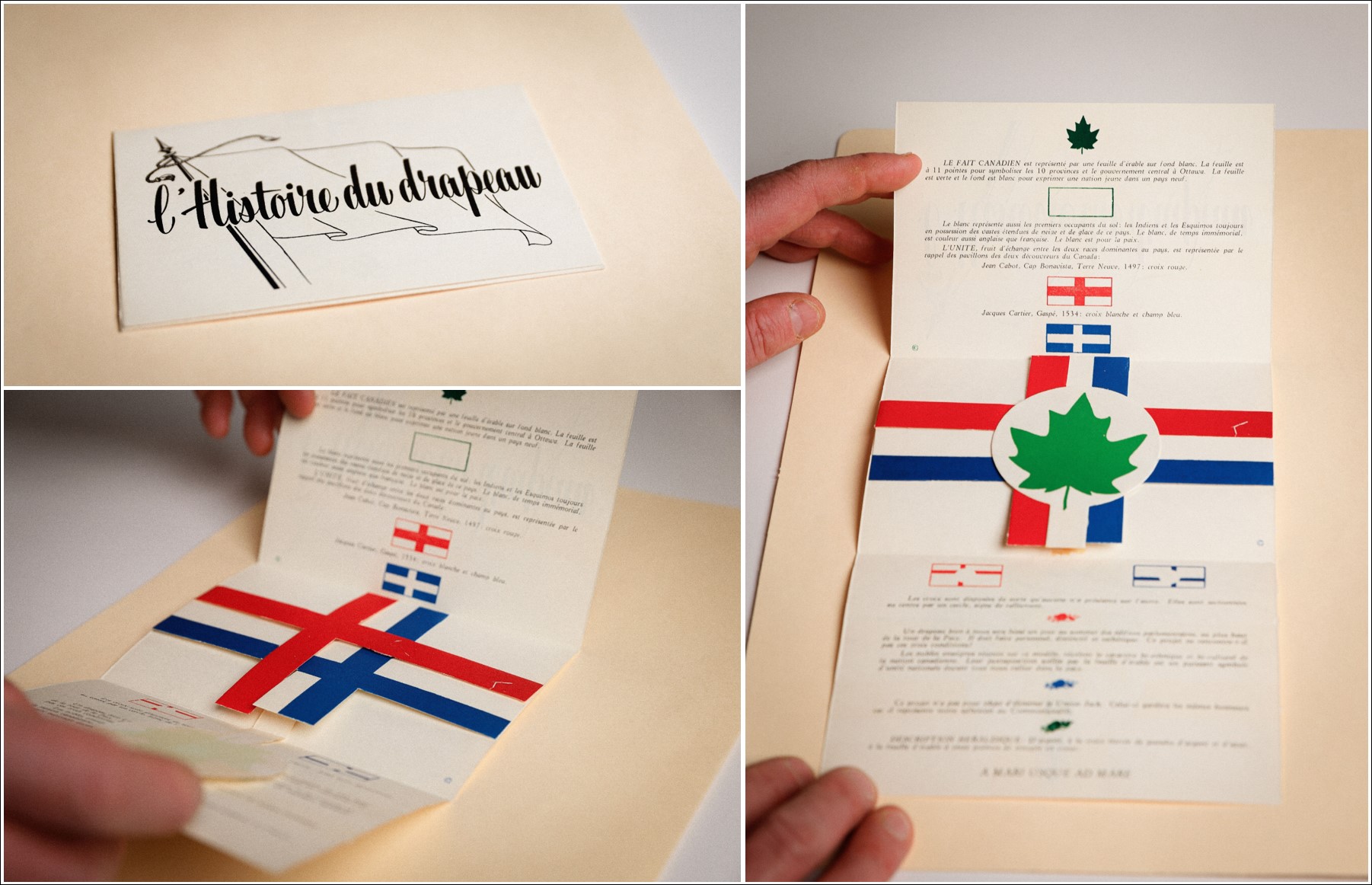

During our conversations, Daniel Dubuc also told me a tantalizing tidbit: his father had produced another piece of ephemera to promote his flag design. It was a foldable model that explained the components of the design and showed how they fit together. Unfortunately, the family did not have a copy, at least not at hand. I made a mental note to keep an eye open for one.

Then in 2022, I found it. I was going through the papers of Guy Marcoux, a Ralliement des créditistes (Social Credit) MP for Québec-Montmorency, not far from Dubuc’s home in Sainte-Foy. In Marcoux’s substantial reference file on the flag question, the Dubuc model stood out among dozens among letters, leaflets and collage flag mock-ups.

Jean Dubuc’s folding flag model. (Library and Archives Canada, Fonds Guy Marcoux, MIKAN 110969)

As I had suspected from Daniel Dubuc’s description, Jean Dubuc’s flag model was inspired by a similar model depicting the history of the Union Jack, distributed by Laura Secord as a promotional favour in the 1930s. Like Dubuc’s model, the Laura Secord version illustrated the layers of crosses, colours, and meaning that made up the Union Jack, Canada’s official national flag for domestic purposes until 1946. The concept was popular: Laura Secord adapted its insert to support the war effort, and American sister company, Fanny Farmer Candy Shops, distributed a similar favour explaining the history of the Stars and Stripes.

Folding model of the Union Jack produced by Laura Secord Candy Shops to mark the coronation of King George VI, 1937. (Library and Archives Canada. National Archives of Canada Postcard Collection. MIKAN 15178)

In his personal campaign for a distinctive flag, Jean Dubuc adapted a format—the folding paper model—that would have been familiar to decision-makers and ordinary Canadians, especially if they were chocolate lovers. His simple, striking design lent itself to this elegant promotional form. My rediscovery of Dubuc’s flag model reminds us also that although the records of the flag committee have been well publicized, there are other collections at Library and Archives Canada that continue to yield surprising details of the Great Flag Debate sixty years later. When you open an archival box, as when you open a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get.

Forrest Pass is a curator with the Exhibitions team at Library and Archives Canada.