![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=519)

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

Last year my colleague Beth Greenhorn and I were chatting about a photograph she had come across of two Inuit women and a child. They were wearing elaborate atigii (inner parkas) with a cloth background behind them. One of the women was wearing odd mittens—one black and one with a distinctive knitted diamond pattern. I was sure I had seen this woman before. I have been researching Inuit tattoos for over ten years, as part of my own art practice. At first, I just collected images and did not take note of the source of the material, something I have been kicking myself for ever since! A few years ago, I started creating a more detailed collection, saving the original image identification numbers. When I began working at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), in 2018, I started searching through our collection for more images and created a list for future reference. In that list, I found “Hattie.”

At least four different people have photographed “Hattie”: George Comer, Geraldine Moodie, Albert Peter Low, and J.E. Bernier. In some photos, I think she has been misidentified. In others, a different woman is also called “Hattie,” “Ooktook,” and “Niviaqsarjuk.” This is perhaps because the women had similar-sounding names, or they were thought to look alike, or the photographer simply got confused after returning to the south and having the photographs processed.

Another institution instrumental to my work that informed my findings is the Glenbow Museum. This museum houses the Geraldine Moodie collection, which also includes photographs of women from the same region and time period. In the Glenbow descriptions, and in a comment on our Project Naming Facebook page, this woman was identified as Ooktook. Through Project Naming, people are identified by community members. For this reason, I consider it to be the most reliable source.

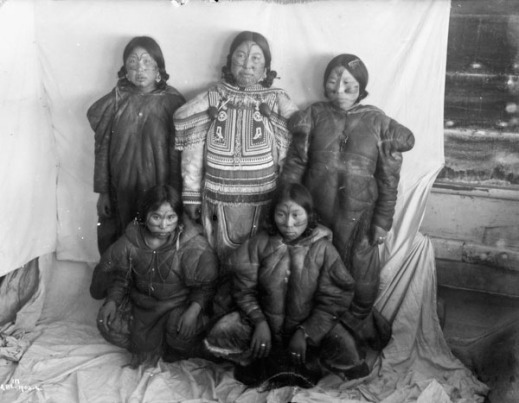

In the image above, one can see the woman seated at front and centre is the same person Ooktook/Niviaqsarjuk/Hattie. She is wearing the exact same outfit as in the photo by Comer right down to the patterned mitten on her left hand, except that, in this photo, she has facial tattoos. In the original photo Beth shared with me, her face is bare! What does this mean? Is it the same woman? Are the tattoos draw on? Were they tracing pre-existing tattoos, or were they completely fabricating these designs?

Recently, I came across an interesting article about the photographic work of Michael Bradley and his project Puaki, which featured photographs of Maori people of New Zealand, well-known for their facial tattoos called Tā moko. The process Bradley uses is wet plate collodion, popular in the 1800s. When Maori people with tattoos were photographed by means of this process, their Tā moko disappeared! The collodion process could not properly capture colours in the blue/green spectrum. Is this what happened with the tattoos of Inuit women from the early 1900s?

With the guidance of Joanne Rycaj Guillemette, the Indigenous Portfolio archivist for Private Archives here at LAC, we did some digging to see exactly which photographic process was used in this photograph of Niviaqsarjuk. Mikan (LAC’s internal archival catalogue) did not have the answer; neither did the former paper-based filing system. The Comer collection of photos are actually copies, and it turned out the originals are held at the Mystic Seaport Museum, in Connecticut. Going through my personal collection of photos, I found an image that looked familiar, and then searched the Mystic Seaport Museum for the ID number. I found the woman referred to by Comer as “Jumbo.” In the description, I found what I was looking for. It states:

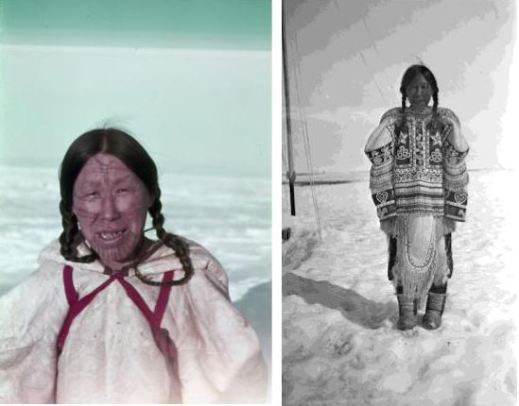

Glass negative by Capt. George Comer, taken at Cape Fullerton, Hudson Bay, on February 16, 1904. Comer identified this image as a young girl known as Jumbo, showing the tattooing of the Southampton Natives. This is one of a group of photos taken by Comer to record facial tattooing of various Inuit groups of Hudson Bay. He had Aivilik women paint their faces to simulate the tattooing styles of various other groups. Information from original envelope identifies this as Photo 55, # 33. The number 30 is etched into emulsion on plate. Lantern slide 1966.339.15 was made from this negative. Identical to 1963.1767.112. 1963.339.58 shows the same young woman in a similar pose.

This was the confirmation I needed that the designs were in fact painted on and that the designs were from other regions! I do not know how often this happened, but finding similar images from other collections has me concerned about the authenticity of tattoo designs in photographs from this period and into the 1950s. I searched the Comer collection further and found more than one woman photographed with and without tattoos, including the woman called “Shoofly,” Comer’s “companion,” whose real name was Nivisanaaq.

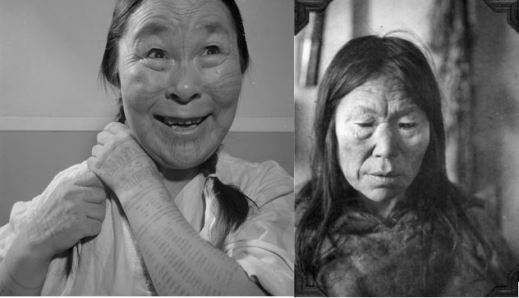

In the Donald Benjamin Marsh fonds, also held at LAC, we see another example of painted tattoos. The unidentified women from Arviat in these two photographs by Donald Benjamin Marsh are most likely the same person, as one can tell from comparing their facial features, especially the broken or missing tooth on the left side of her mouth. On the right side of her face, she has no tattoos; on the left side, however, the tattoos are quite prominent. The lines are very dark and wide. When one compares these images to photographs of women with authentic tattoos, one can see the difference. Here, the lines are quite fine and faint, but still visible.

This discovery reminds me of the actions of well-known photographer Edward S. Curtis, who travelled through North America photographing Native American peoples. (Note: We use the term “First Nations” in Canada, but “Native American” is used in the United States of America). Curtis often manipulated scenes by dressing sitters in clothing from an earlier era, removed contemporary elements, and added props that created a romanticized and inauthentic representation of them. Not only is this type of manipulation dehumanizing, it leaves behind a legacy of misinformation.

As a reaction to colonialization and assimilation policies, Indigenous Peoples are going through a period of cultural resurgence. When those of us who are looking to reclaim elements of our culture, such as tattooing, come across these images and assume the designs originate in the region the people are living in. Someone in Arviat, seeing a photo of her great-grandmother, for example, might want to reclaim the markings of her relative and mistakenly get the same markings, not knowing the design is from a completely different family and region. One can only imagine how distressing this would be.

A main goal of We Are Here: Sharing Stories is to update descriptions to make them culturally sensitive and accurate. To this end, we are updating descriptions for the above-mentioned collections, to add the women’s correct names if known and a note explaining the significance of the tattoos. This note also addresses the practices of some photographers of the time that may result in tattoo designs that are not authentic to the women or their region. Although we cannot change the past, it is my hope that these actions will help inform researchers and community members alike from this point on. Nakurmiik (thank you).

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.