By Sali Lafrenie

“What a trip. It was as if I had been shot through a time tunnel from the fields of Willowdale to a field of dreams. The many threads of my life have all come together to produce a beautiful tapestry.”

Herb Carnegie, A Fly in a Pail of Milk: The Herb Carnegie Story (OCLC 1090850248)

Herb “Swivel Hips” Carnegie (1919–2012) was an exceptional athlete with multiple golf championships and an impressive career in hockey spanning over a decade. During his playing career, he travelled to numerous cities and played at the amateur and semi-professional levels for teams like the Toronto Observers, the Toronto Young Rangers, the Perron Flyers, the Timmins Buffalo Ankerites, the Shawinigan Cataractes, the Sherbrooke Randies (also known as the Saints), the Quebec Aces and, in his last season, the Owen Sound Mercurys. Carnegie had a decorated sports career, winning MVP for three straight years in the Quebec Senior Hockey League (QSHL) and playing on the first all-Black line in semi-pro hockey since the Colored Hockey League.

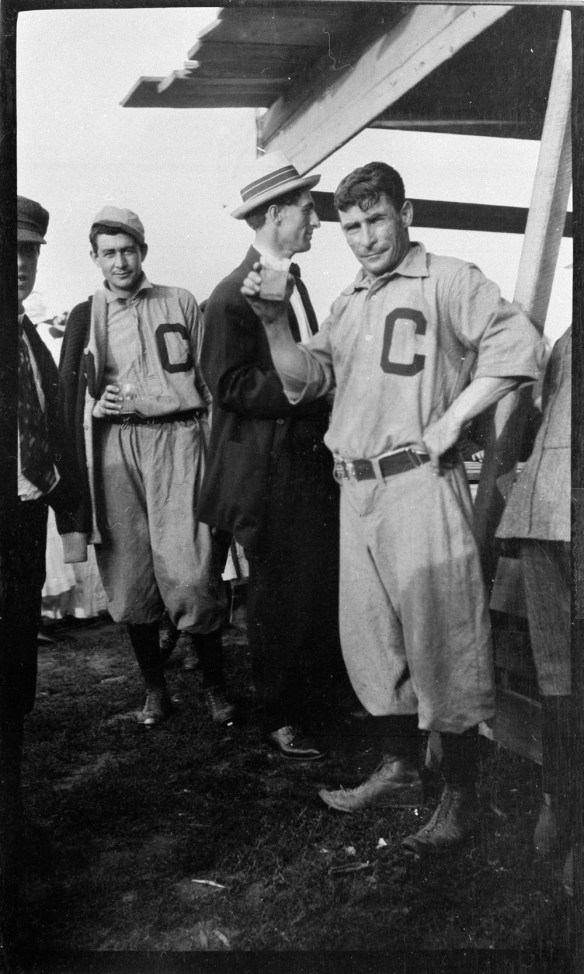

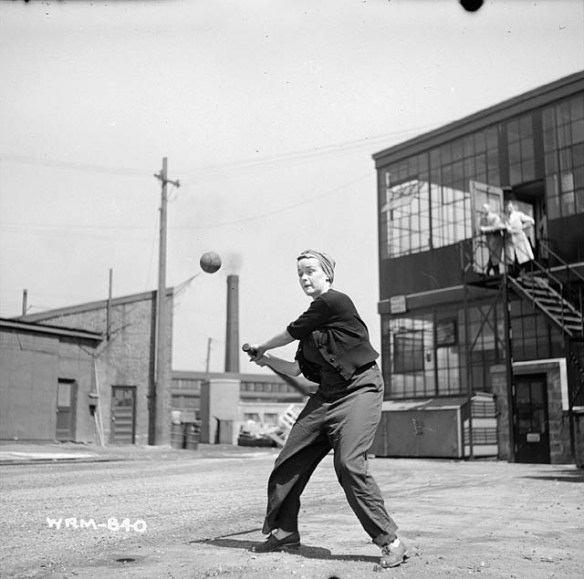

A photo of the famous all-Black Line: Herb Carnegie, Ossie Carnegie, and Manny McIntyre. (Library and Archives Canada/e011897004)

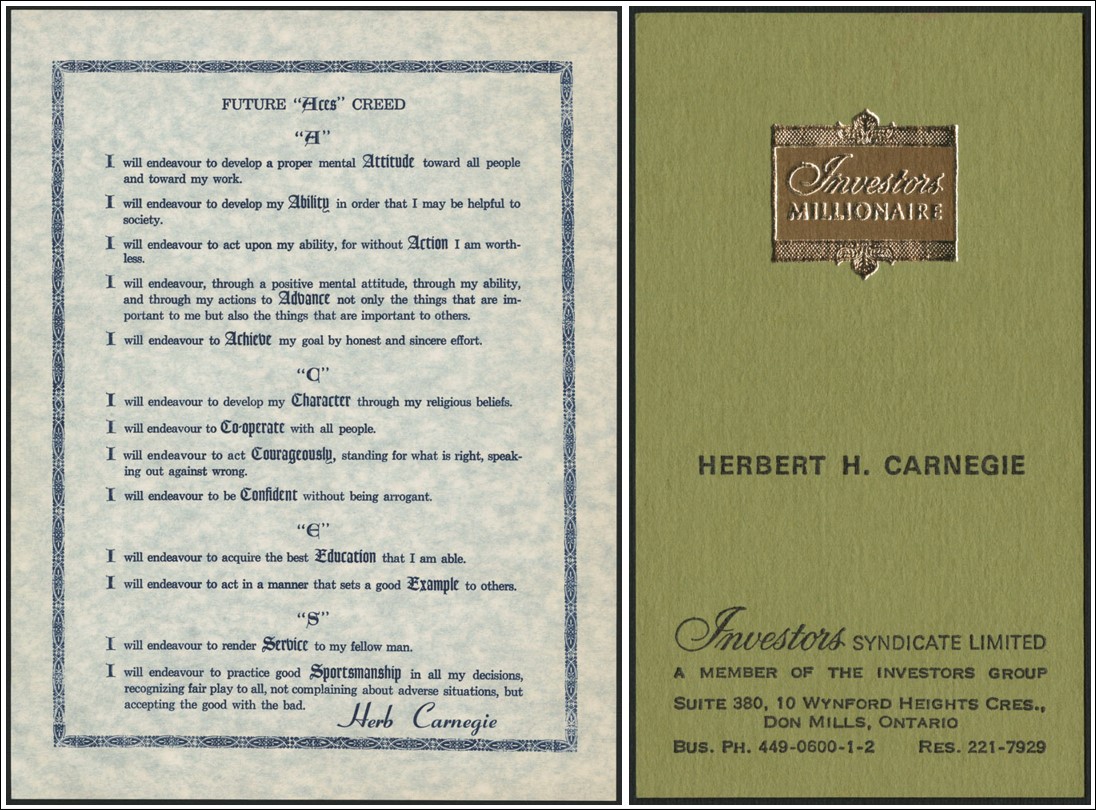

After hanging up his skates, Carnegie became a successful businessman and the first Black Canadian financial advisor employed by Investors Group. He had a 32-year long career with Investors Group, and an award was established in 2003 in his honour: the Herbert H. Carnegie Community Service Award. Carnegie was more than just an example of business excellence; he was a community leader and an entrepreneur. He founded one of the first hockey schools in Canada, invented a hockey instructional board and devised a board game with the hope of helping people understand the sport and improve their hockey IQ. Further, Carnegie established the Future Aces Foundation and Philosophy alongside his wife and daughter, Audrey and Bernice. His impact can be seen in many places like the comic book features he received, the halls of fame he has been inducted into, the awards named after him, and the schools that adopted his Future Aces Creed (there is even a school named after him).

Future Aces Creed and Investors Millionaire Card. (Library and Archives Canada/e011897005 and e011897007)

But what’s in a name?

I’d disagree with Shakespeare, at least in this instance, and say that names do have power. They have histories, they have legacies, and they can act as maps. The Carnegie name does this for the world of sports, entrepreneurship, business, labour, and nursing.

Drawing attention for his skills and style of play, along with his race, there is even more we can learn from Herb Carnegie’s ice time if we stop to ask a few questions:

- How does Herb’s experience in hockey reflect larger issues in Canadian society at the time?

- If Black hockey players existed in 1895, why wasn’t the colour barrier in the NHL broken until 1958 by Willie O’Ree?

- Whose shoulders are hockey players of colour standing on today?

While Herb Carnegie is often remembered for his exceptional hockey skills and for being the best Black hockey player to never play in the NHL, his impact off the ice has also been significant. He deserves to be remembered for all his contributions and for all the ways he and his family have worked for generations to make their communities better.

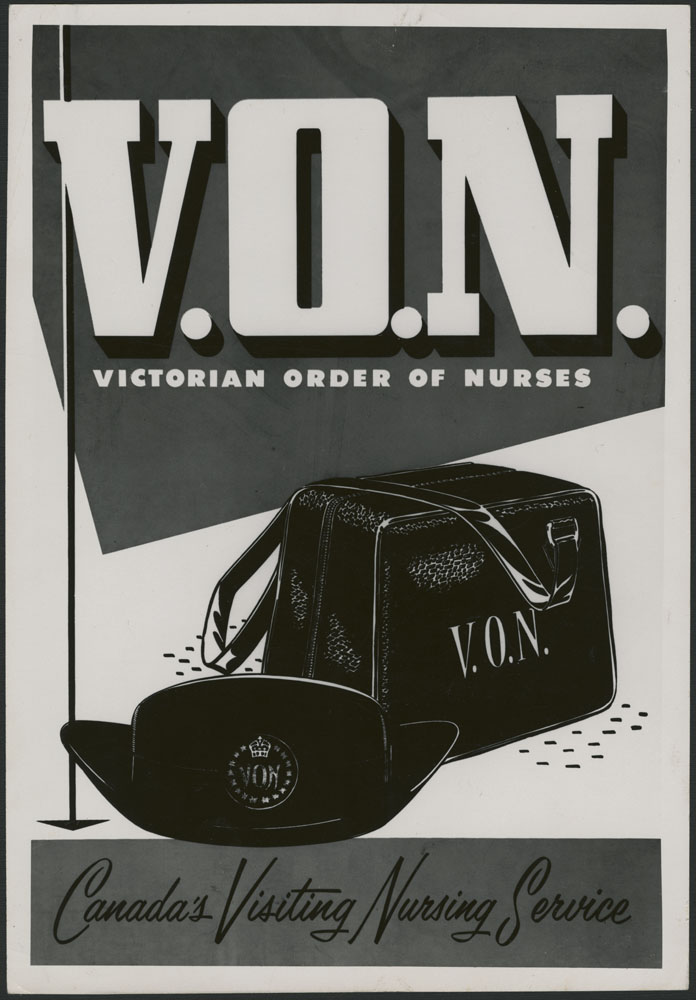

Pivoting to Herb Carnegie’s sister, we find Bernice Isobel Carnegie Redmon, the first Black public health nurse in Canada (1945) and the first Black woman appointed to the Victorian Order of Nurses in Canada (VON). We can learn more about the context of nursing and blackness in Canada by asking more questions:

- How did Bernice Redmon become the first Black public health nurse in Canada in 1945?

- What prevented Black women from entering the field before World War II?

- When did the first Canadian nursing program start?

A quick search tells us that Bernice Redmon trained to become a nurse in the United States because Black women were prohibited from training as nurses in Canada until the mid-1940s, and that while the VON was established in 1897, the first Canadian nursing program opened in 1919. However, Bernice Redmon was not alone for long, as Ruth Bailey, Gwen Barton, Colleen Campbell, Marian Overton, Frieda Parker Steele, Cecile Wright Lemon, Marisse Scott and Clotilda Douglas-Yakimchuk joined her in the following years. Despite the roadblocks and unofficial policies like quotas, the face of medicine and nursing began to change in the 1940s and 1950s. This year marks the 80th anniversary of Bernice Redmon’s achievement.

Victoria Order of Nurses poster. (Library and Archives Canada/e011897008)

Shifting to the next generation of Carnegies, we find Bernice Yvonne Carnegie, Herb’s daughter. She is the self-dubbed family historian and a leader in the hockey community, co-founding the Future Aces Foundation with her parents and establishing the Carnegie Initiative in 2021. Like her father, Bernice is working to support her community and to ensure that hockey is more inclusive. She has been giving back for over a decade through educational programming using the Future Aces Philosophy, academic grants, and her work as a public speaker. Moreover, she was a member of the BIPOC ownership group that purchased the Toronto Six hockey team.

In 2019, Bernice updated her father’s memoir, A Fly in A Pail of Milk, by sharing her own reflections on his life, lessons learned, and how she has continued the work he started. Once you read Herb Carnegie’s memoir and her reflections, it’s hard to stop there. I found myself diving into the family histories she maintains online, and I was struck by how deep the roots between her family and Canada run. I found myself asking questions again:

- What jobs were available to Black men between 1900 and 1950?

- What was the average salary at a mining company? What about for hockey players?

- How do we define the Carnegie family’s multigenerational legacy?

Trailblazing is exciting, but it’s also important to remember that the individuals who broke through colour bars, de-segregated schools, and advocated for their inclusion are people too. In their extraordinary achievements, they face obstacles, racism and often trauma at the hands of the organizations they admire. Navigating predominantly white institutions is not easy; it has a cost. Being the first or one of few is challenging. It’s not often that we take the time to think about how history maps onto our lives and our families. Like the Carnegies, I know there are other families in Canada whose lives and family trees contain branches that blaze a trail through the national landscape. Without hesitation, I can think of families like the Nurses, the Grizzles, the Crowleys and the Newbys.

So, what’s in a name? A tapestry. A history. An archive.

Additional resources

-

- A Fly in a Pail of Milk: The Herb Carnegie Story by Herb Carnegie and Bernice Carnegie (OCLC 1090850248)

- Blackness is a gift I can give her: essays on race, hockey, and culture by R. Renee Hess (OCLC 1418890268)

- Herb Carnegie, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 3728928)

- Employment record cards, Camley to Carnegie, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 4742072)

- Uninterrupted Canada Inc. fonds (MIKAN 6053840)

- Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada fonds (MIKAN 99815)

- Episode 2 | Strong and Free | Herb Carnegie: Black Excellence on – and off – the Ice | Historica Canada

- Jackie Robinson and the baseball colour barrier, by Dalton Campbell, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Fergie Jenkins’s Long and Grinding Road to Cooperstown, by Kelly Anne Griffin, Library and Archives Canada Blog

Sali Lafrenie is an archivist in the Private Archives and Published Heritage Branch at Library and Archives Canada.