Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Join us every month during 2017 as experts, from LAC, across Canada and even farther afield, provide additional insights on items from the exhibition. Each “guest curator” discusses one item, then adds another to the exhibition—virtually.

Be sure to visit Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? at 395 Wellington Street in Ottawa between June 5, 2017, and March 1, 2018. Admission is free.

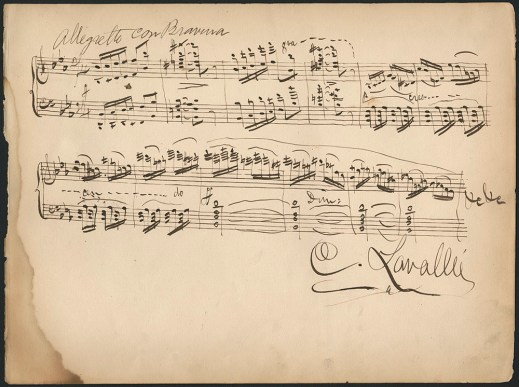

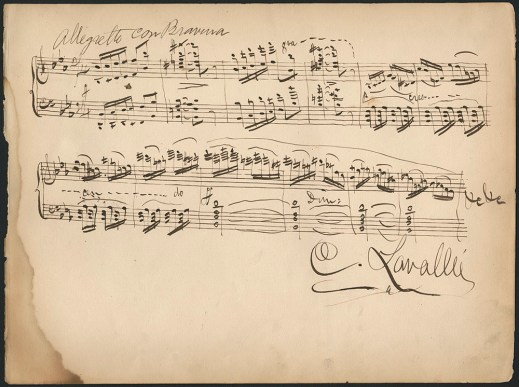

The opening measures of “Une Couronne de Lauriers” by Calixa Lavallée, ca. 1864

Sheet music of “Une Couronne de Lauriers” by Calixa Lavallée, ca. 1864 (MIKAN 4903777)

Calixa Lavallée didn’t think Canada would work as a nation. He may even have written anti-Confederation music. There were certainly heavy hints in the newspapers about a radical known for his crown (couronne) and laurels (lauriers).

Tell us about yourself

As a boy, hockey, music, history and politics all fascinated me. The first two I had in common with most kids my age. The third and fourth were more obscure. Nevertheless, as a musicologist, I made music, history and politics part of my work, and while writing about Calixa Lavallée, the composer of “O Canada,” I realized that I had found a way to bring hockey into the mix—the national anthem, as sung by the great Roger Doucet, had been a part of my Saturday nights from fall until spring.

Is there anything else about this item that you feel Canadians should know?

Lavallée was born just outside Montréal in 1842. By the time he was in his mid-teens, he was a professional musician, employed as musical director of travelling minstrel troupes and performing as a pianist. He would go on to become an important educator, both in Canada and the United States, and a composer of nearly every form of music common in his time. His published works include songs, sacred music, concert overtures, operas, numerous piano pieces and “O Canada,” which he composed in 1880.

Lavallée returned to Montréal from the U.S. in 1863 and remained until late in 1865. It was a momentous time on both sides of the border. In 1864, while the U.S. Civil War entered its third year, Canadians began to debate the merits of Confederation. In Montréal, opinions were divided on the creation of a new country. Through his contributions to nationalist newspapers La Presse and l’Union nationale, the 22-year-old Lavallée aligned himself with opponents of Confederation who believed it would lead to the assimilation of French Canadians. On stage, he maintained a high profile, leading a group of young vocalists and instrumentalists in numerous concerts, and devoting much of his time to raising funds for charity.

On February 19, 1864, Lavallée gave a concert at Nordheimer’s Hall, in Montréal, and played “Une Couronne de Lauriers” for the first time in public. The local firm of Laurent, Laforce et cie published it that summer, and in August La Presse printed a review of it by the pianist Gustave Smith, who called it “the first major piece that has been issued by a Montréal music publisher” [« la premier morceau d’importance qui ait paru chez un éditeur de musique de Montréal »]. It would seem likely that Lavallée jotted down these opening bars of “Une Couronne de Lauriers” at about this time.

Autograph sheets containing signatures from major opera singers of the time (MIKAN 4936687)

This fascinating document raises many questions. It was acquired by LAC together with a double-sided sheet titled “Autographes des dames et messieurs de l’Opéra Italien.” Markings clearly indicate that the first sheet, containing a musical fragment, was from the same book as the second, a page of autographs. They were both acquired by LACthrough a rare book dealer, and we can now only speculate on their origins and purpose.

The autograph sheet contains the signatures of many opera personalities of the time, including the impresario Max Strakosch and the mezzo-soprano Amalia Patti Strakosch. Most of the performers, if not all, were active in New York City in the mid-1860s. The page also contains a cryptic message: “What will be the future for us? Montréal 5 Nov. 1866” (« Que sera l’avenir pour nous deux? Montréal 5 nov 1866 »).

So, to whom did these two sheets belong? I can only speculate. One possibility is that they were the property of Lavallée himself, perhaps passed on to his widow after his death in Boston in 1891, and then to someone else. Lavallée often worked with opera singers and may have collected their autographs. A photograph album that he owned has survived and contains many signed pictures of other artists. It would, however, have been unusual for him to have contributed a short piece of music to his own autograph book.

Perhaps a more likely possibility, then, is that these pages were the property of the pianist Gustave Smith. He was Lavallée’s colleague in Montréal in the 1860s, and he also often worked with opera singers. He too left for the U.S. late in 1865, or in early 1866, staying for a brief period in New York before settling in New Orleans. He returned to Canada later that decade to take a position as organist in Ottawa’s Catholic cathedral.

A third possibility is that these items belonged to another of Lavallée’s collaborators: the violinist Frantz Jehin-Prume. This Belgian musician paid an extended visit to Montréal in 1865, during which time he performed at least once with Lavallée. The two later became close friends and frequent performing partners. He toured on more than one occasion with a company that included Amalia Patti Strakosch. He was in New York City in the fall of 1865 and returned to Montréal in 1866.

While this manuscript still has secrets to reveal, it provides a little window into the past, giving us a glimpse of cultural life at the time in which Canada was being conceived and into the life of the musician whose music would help to define a country to whose creation he initially objected.

Through their training and experience, historians and archivists—and musicologists—learn the potential importance of a handwritten document. They know that a letter, a memo or a few notes of music written quickly on a scrap of paper may help us to better understand an earlier time and may hold far more value than is immediately apparent. Studying history can be about analyzing major historical and political events, but it can also be detective work. Those exploring our time are likely to rely largely on information in electronic formats: digital images, emails, posts, blogs. This exhibition may then provide an opportunity for the public to consider and admire original documents, such as these—documents created by human hands, and by people who have left something of themselves and their time for the future.

Tell us about another related item that you would like to add to the exhibition

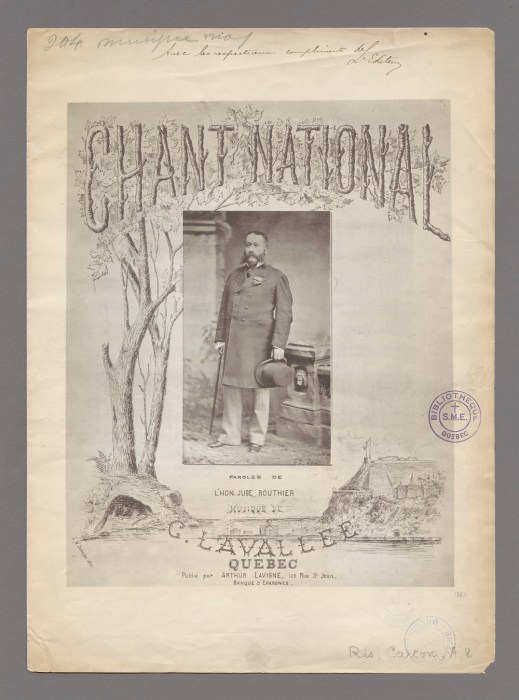

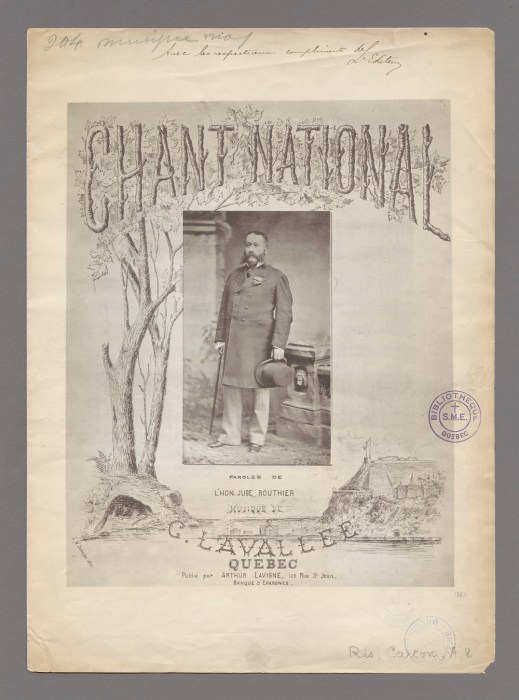

Cover of the first edition of “O Canada” (AMICUS 5281119) L.N. Dufresne, cover “O Canada” (Québec: Arthur Lavigne, 1880). Musée de la civilisation, bibliothèque du séminaire de Québec. Fonds ancient, 204, SQ047145.

The cover of the first edition of “O Canada” (“Chant national”) is a rare item of important historical significance. The anthem was composed for the Congrès Catholique Canadien-français of 1880, a gathering of intellectuals, politicians and thousands of members of the general public, intended to celebrate French-Canadian culture and reflect on the future. The event included many musical performances. It was also seen as an opportunity to create a national song that had the dignity of “God Save the Queen,” the anthem then sung at all public events in Canada.

The organizing committee of the Congrès selected Calixa Lavallée as the composer, and judge Adolphe-Basile Routhier as the poet, of the new anthem. Both were then living in Québec and knew each other at least casually. They completed their work by April of 1880 and newspapers announced that it would published by the local music dealer Arthur Lavigne. The cover’s designer was L.N. Dufresne, a painter and illustrator. Dufresne intended his artwork to capture visually the essence of the music. The title is presented at the top, surrounded by maple garlands. On the right is the Québec Citadel, on the left a beaver, at the bottom the St. Lawrence River. The centre of the page features a photograph of Lieutenant-Governor Théodore Robitaille. His prominence on the cover was an acknowledgement of his place as a patron of the arts and a leading proponent of the creation of a new national song—a song that he hoped would come to represent the people of Quebec and French-Canadians everywhere.

Biography

Brian Christopher Thompson is the author of Anthems and Minstrel Shows: The Life and Times of Calixa Lavallée, 1842–1891 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2015), and the compiler and editor of Calixa Lavallée: L’œuvre pour piano seul / The Complete Works for Solo Piano (Vancouver: The Avondale Press, 2016). He completed his PhD in musicology at the University of Hong Kong, under the supervision of Michael Noone and Katherine Preston, in 2001, after completing degrees at Concordia University, the University of Victoria and McGill University. He is currently a senior lecturer in the Department of Music at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Brian Christopher Thompson is the author of Anthems and Minstrel Shows: The Life and Times of Calixa Lavallée, 1842–1891 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2015), and the compiler and editor of Calixa Lavallée: L’œuvre pour piano seul / The Complete Works for Solo Piano (Vancouver: The Avondale Press, 2016). He completed his PhD in musicology at the University of Hong Kong, under the supervision of Michael Noone and Katherine Preston, in 2001, after completing degrees at Concordia University, the University of Victoria and McGill University. He is currently a senior lecturer in the Department of Music at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Related resources