Category Archives: Photography

Underwater Canada: A Researcher’s Brief Guide to Shipwrecks

Shipwrecks, both as historical events and artifacts, have sparked the imagination and an interest in the maritime heritage of Canada. The discovery of the War of 1812 wrecks Hamilton and Scourge, found in Lake Ontario in the 1970s, and the discovery of the Titanic in the 1980s, served to heighten public awareness of underwater archaeology and history.

Whether you are a wreck hunter on the trail of a lost vessel, or a new shipwreck enthusiast eager to explore images and documents that preserve the epic tales of Canadian waters, Library and Archives Canada (LAC) has something for you.

Starting your research

First, gather as much information as possible about the shipwreck(s) you are researching. Specifically, you will ideally want to obtain the following information (in order of importance):

- Name of Vessel

- Location of accident

- Date of accident

- Ship’s port of registry

- Ship’s official number

- Year of vessel’s construction

The Ship Registration Index is a helpful resource. The database includes basic information about more than 78,000 ships registered in ports of Canada between 1787 and 1966.

Can’t locate all of the information listed? There’s no cause for concern! Not all of the information is necessary, but it is essential that you know the name of the vessel. All Government records relating to shipwrecks are organized according to the ship’s name.

What is Available?

Using Archives Search, you can locate the following types of material:

Photographs

- Consult the How to Find Photographs Online article for more help.

Maps

- In Archives Search, under “Type of material”, select “Maps and cartographic material” to narrow your results.

Government Records

All records listed are found in the documents of the Marine Branch (Record Group 42) and/or Transport Canada (Record Group 24).

Official Wreck Registers, 1870‒1975

- Wreck Reports, 1907‒1974

- Register of Investigations into Wrecks, 1911‒1960

- Marine Casualty Investigation Records, 1887‒1980

Important: Government records contain information about shipwrecks that occurred in Canadian waters, and include all accidents involving foreign vessels in Canadian waters.

Please note: this is not an exhaustive list of resources, but rather a compilation of some of the major sources of documentation available on shipwrecks held at LAC.

Helpful Hints

You can find a number of digitized photographs, maps and documents on the Shipwreck Investigations virtual exhibition. More specifically, check out the collection of digitized Official Wreck Registers in the Shipwreck Investigations Database. Simply check if the name of the vessel you are researching is listed.

Another excellent source of information on shipwrecks is local public libraries. There are many maritime histories and bibliographies that offer reference points to begin your shipwreck research.

Arctic Images from the Turn of the Twentieth Century

Explorers and travellers have long been documenting their Arctic adventures in diaries, manuscripts, maps, sketches and watercolours. Their accounts portray the Arctic as a mystical land, whose inhabitants and way of life seem unspoiled, and this imagery was further disseminated to audiences abroad with the invention of the photograph.

The following photographs are part of the Arctic Images from the Turn of the Twentieth Century exhibition presented at the National Gallery of Canada. Featuring material from Library and Archives Canada’s collections, the exhibition showcases rarely seen images, which document photographers’ travels in the Canadian north. In many cases, these images present a romanticized view of the people and places.

One of the earliest images is this photograph of a hunter, taken by George Simpson McTavish while he was stationed at the Hudson’s Bay Company at Little Whale River, Quebec, in 1865.

Portrait of a hunter, a beluga, a seal skin “daw” (a buoy), and a kayak along the edge of the Little Whale River, Quebec. Photographer: George Simpson McTavish (MIKAN 3264747)

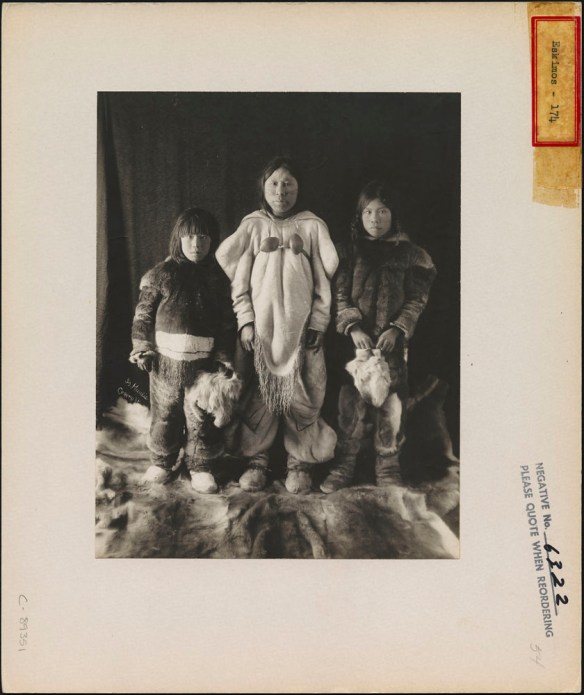

The majority of photographers who ventured to the Arctic regions were men, and for the most part, were employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Canadian government. Geraldine Moodie was one of the few female photographers. She had a successful photography studio prior to moving north with her husband when he was posted to the North West Mounted Police station in Fullerton (Qatiktalik in Inuktitut), Nunavut. Her portrait of an Inuit widow and her children, taken around 1904, is a good example of her beautifully composed images.

Widow and her children, Nunavut, by Geraldine Moodie (MIKAN 3376416)

The vast majority of photographs of Inuit emphasized the ethnological attitudes of the era by presenting them as “types,” such as this 1926 image of an unidentified man.

Unidentified man, Chesterfield Inlet (Igluligaarjuk), Nunavut, by Lachlan T. Burwash, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (MIKAN 3376543)

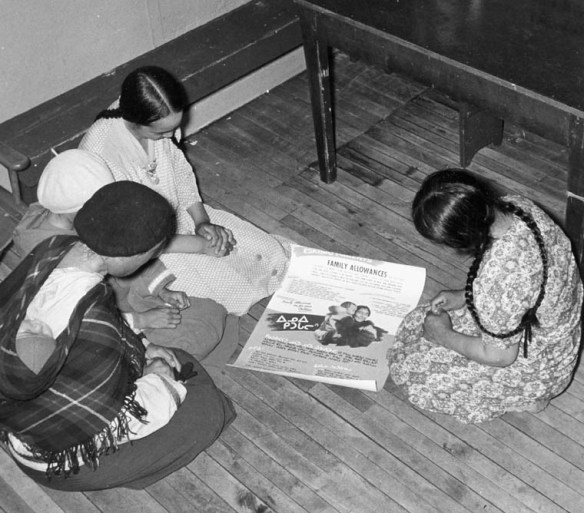

In other cases, Canadian government staff took photographs to highlight federal government initiatives and policies, such as this 1948 image of four women looking at a family allowance poster. Below it, also from Health and Welfare Canada’s Medical Services Branch, is the portrait of Bella Lyall-Wilcox carrying her baby sister, Betty Lyall-Brewster. Taken in 1949, the lighting and composition of this portrait link it aesthetically to the pictorial tradition of the majority of photographs in this exhibition.

Women looking at a family allowance poster, Baker Lake (Qamanittuaq), Nunavut, by unknown photographer, Health and Welfare Canada (MIKAN 3613868)

Bella Lyall-Wilcox (left) and Betty Lyall-Brewster, Taloyoak (formerly Spence Bay), Nunavut, by Studio Norman, Health and Welfare Canada (MIKAN 3613832)

The Arctic Images from the Turn of the Twentieth Century exhibition opened on March 14, 2014, and will continue until September 1, 2014, at the National Gallery of Canada. For more information about LAC’s photographic collections portraying Inuit and the Arctic, visit our Project Naming web page.

Insight into Library and Archives Canada’s collection: interview with photographer Martin Weinhold

Recently, the Library and Archives Canada Discover Blog had a chance to interview documentary photographer Martin Weinhold about some of his photographs of Canadians at work, held in Library and Archives Canada’s collection.

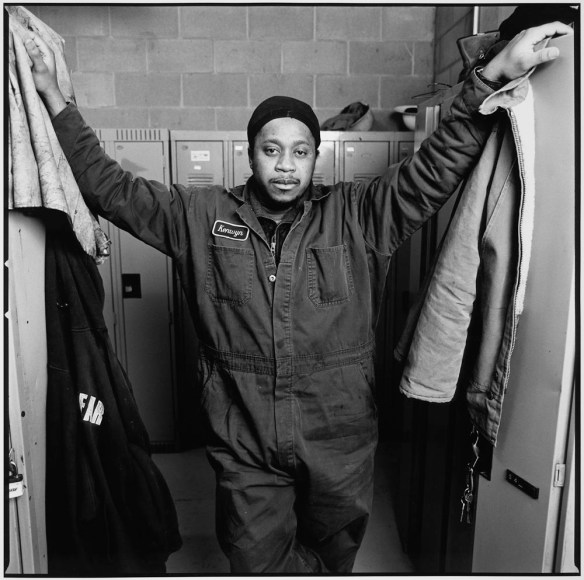

Kenwyn Bertrand, I, worker. MIKAN 3842771, e010934568

- These photographs are part of a larger series. In just a few words, please tell us what series this is and what inspired it?

- Please tell us why you chose to take three different photographs of the same subject?

- How can we tell that these are Martin Weinhold photographs?

The photographs are part of the “WorkSpace Canada” collection, a long-term project that still is a work in progress. The project’s goal is a general description of the world of work in Canada in the early 21st century; a kind of visual inventory centred around the human aspect of labour, work and action. The idea for this photographic documentary was triggered in 2005 when I read Hannah Arendt’s book “The Human Condition.”

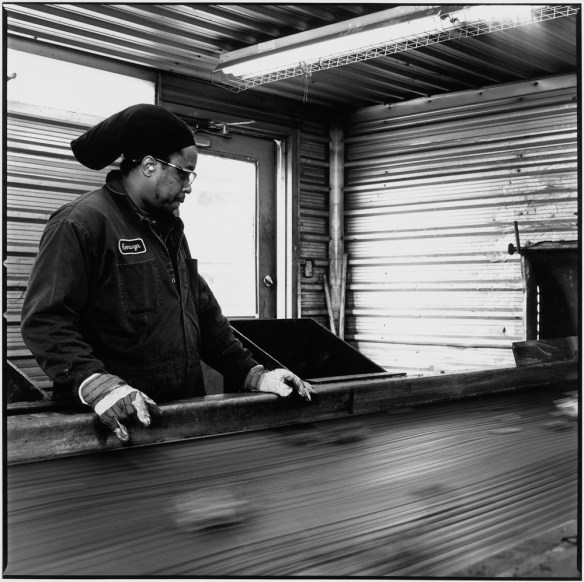

Kenwyn Bertrand, II, worker. MIKAN 3842782, e010934567

I wanted to introduce Kenwyn Bertrand, a worker at a car shredder yard in Hamilton, Ontario, with a threefold approach: giving the viewer a notion of the work environment and the activity happening there, as well as showing a facet of his individual personality. This pattern is the general approach for the “WorkSpace Canada” series.

When I came to the car shredder yard I had a kind of production schedule already in mind. From previous visits and observations I knew the so-called picking shacks were one part of the operation, and I knew they were a must in the overall description of the place. I wanted to visually translate what it was like being on shift there. Kenwyn and I discussed what would be important for me to photograph and what wouldn’t. For Kenwyn, being at his workplace meant this repeated waiting for the copper parts among the rubbish on the conveyor belt—the whole reason his job existed. Then there was the locker room, the place where every shift began and ended. And the only possible place for a portrait. Although for privacy we had to wait until every worker from Kenwyn’s shift had left.

Kenwyn Bertrand, III, worker. MIKAN 3842786, e010934566

I think—I hope—the intensity of my dealing with the subject can be seen. I try to establish an intense relationship with every person I photograph. Time is the crucial precondition for that. Time is the luxury I insist on having with my documentary work. If the viewer can read the intensity in my photographs and see it as typical for a Martin Weinhold photograph—that would make me very happy.

Images of the Battle of Ortona Now on Flickr

Where art and history meet: exhibitions of historical photographs at the National Gallery of Canada

What happens when the practical also has a poetic side?

In recent months, visitors to the National Gallery of Canada have had a chance to explore the answer to this question. A series of small exhibitions of historical photographs, drawn from Library and Archives Canada’s collection, considers the aesthetic, as well as the documentary properties of images created “on-the-job” by 19th-century surveyors, public servants and engineers.

In the heart of the Rocky Mountains: A snowstorm, by Charles Horetzky (Source: MIKAN 3264251, e011067226)

At first glance, this beautiful photograph, which was part of the past exhibition Early Exploration Photographs in Canada, seem to be exactly as labelled — a view of the Peace River in British Columbia, as it appeared during a snowstorm in October 1872. It turns out, however, that Charles Horetzky, official photographer with Sir Sandford Fleming’s Canadian Pacific Railway survey team, deliberately enhanced its dramatic effect: paint splatters were added to the image in order to create the effect of non-existent snow.

The current exhibition, Paul-Émile Miot: Early Photographs of Newfoundland, on view until February 2, 2014, includes this portrait from the 1800s, by French naval officer Paul-Émile Miot.

Mi’kmaq man, by Paul-Émile Miot (Source: MIKAN: 3535989, e011076347)

It was taken while surveying and mapping the coastal areas of Newfoundland — at the time, France maintained a commercial fishing interest in these waters. Though Miot was capturing the earliest known photographs of members of the Mi’kmaq Nation, the extravagant pose of his subject suggests 19th-century European romanticism.

So-called inaccuracies or created effects in 19th-century documentary photographs do not negate the worth of these images as records of past events. If anything, they add fascinating nuances of meaning to these items, as artifacts.

We invite you to stay tuned for the next exhibition, on Arctic exploration photography, opening on February 7, 2014.

About Face: Library and Archives Canada portrait exhibition at Queen’s Park

Three original works of art and over 30 high-quality reproductions from the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) portrait collection are on display in the Lieutenant Governor’s Suite at Queen’s Park in Toronto until March 31, 2014. The portraits are part of About Face: Celebrated Ontarians Then and Now, an exhibition developed by the Office of the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario in collaboration with LAC. These historical and modern portraits represent men and women from a wide range of cultural backgrounds and walks of life, who helped shape the Ontario of today.

This rare portrait of Maun-gua-daus, for example, is one of the earliest photographs of an Indigenous person in LAC’s collection. A member of the Ojibway nation, Maun-gua-daus was educated by Methodist missionaries and served as a mission worker and interpreter in Upper Canada (now Ontario). From 1845 to 1848, he took part in a tour of England, France and Belgium, demonstrating the ritual, dance and sport found in Ojibway culture. This photograph was probably taken during that tour, in about 1846. It was made using the daguerreotype process, the first method widely used for producing photographic images.

Maun-gua-daus (or Maun-gwa-daus), alias George Henry, original chief of the Ojibway nation of Credit (Upper Canada) (Source: MIKAN 3198805)

An iconic portrait of figure skater Barbara Ann Scott was taken in 1946 by another notable Ontarian, Yousuf Karsh. At the time, the young lady from Ottawa was a Canadian national champion, but had yet to win a European championship and a world figure-skating title. Scott became “Canada’s sweetheart” and Olympic gold-medal champion in 1948, at the age of 19. In this photograph, Karsh frames the skater’s youthful face in what appears to be a saintly halo.

Barbara Ann Scott (Source: MIKAN 3192044)

Come see for yourself! Contact the Office of the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, Queen’s Park to arrange a viewing of the exhibition.

How anonymous or little-known portrait sitters tell the Canadian story

No names are recorded on this 1913 photograph of an Ontario boys’ band.

Boy’s Brass Band Community Movement Pembroke, circa 1913. Source

Although the leader, “Bandmaster Wheeler,” is identified in a second photograph of this same group, we have found little information about him or the group of boys that he taught.

Bandmaster Wheeler and Boy’s Brass Band Community Movement Pembroke, circa 1913 Source

A surprising number of portraits in Library and Archives Canada’s (LAC) collection are anonymous or little–known men, women and children. We may never know the identity of these people or discover more about their lives, yet these portraits are as important to LAC’s collection as portraits of well-known people.

These boys’ band photographs document an interesting social movement at the beginning of the 20th century. Community organizations concerned about the morals and manners of their children sponsored bands for young boys. Participation in these bands was seen as a way of learning community service and developing local and national pride.

Viewed together, these photographs illustrate this idea. We know that the first photograph was taken slightly earlier because the boys wear suits rather than band uniforms. Local records of the time show that they were still raising money through performances to earn their uniforms. The second photograph shows the group in uniform — the reward for learning this lesson in personal responsibility and hard work.

These group photographs probably helped to cement the band’s unity and team spirit. Membership in this band looks as though it might have been a lot of fun too, judging by Bandmaster Wheeler’s slightly loosened tie in one photograph, and the jaunty angle of his hat in the other. Wheeler is an interesting figure, being an early Black bandmaster in small-town Ontario. LAC holds few portraits of Black Canadians from this period. Wheeler’s presence in these photographs provides us with an important record.

We continue to research the identity of unknown portrait sitters. If you can help, please contact us.

To view other examples of anonymous or little-known sitters in LAC’s portrait collection, visit our Flickr Album.

Anonymous portraiture images now on Flickr

The Mountain Legacy Project: An Archive-Based Scientific Project

Beginning in 1871, the Dominion Lands Branch had been surveying and mapping Canada from East to West. By 1886, the Dominion Lands Survey had extended to the Rocky Mountains, but the rugged terrain made traditional survey methods impractical. Édouard-Gaston Deville, Surveyor General of Canada, devised a new methodology called “phototopography,” (also known as photogrammetry) based on the use of survey photography from hot-air balloons in France and Italy. A special camera was constructed for surveyors, who ascended thousands of peaks in Alberta, British Columbia and the Yukon. They rotated and levelled their cameras on tripods to create 360-degree views of the surrounding terrain. Between 1887 and 1958, more than 100,000 glass plate negatives were used to create the first topographic maps of the Canadian Rockies, of which 60,000 are now part of the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) collection.

Since 2002, LAC has been a major participant in the Mountain Legacy Project, an ongoing partnership led by the University of Victoria, which includes stakeholders in universities, archives, government, and non-governmental organizations.

LAC identifies, describes and digitizes the original negatives. These photographic records are the foundation of this multidisciplinary project, which uses “repeat” photography. It consists of re-photographing the landscape from the precise original locations to provide information about environmental changes that have occurred over the last 120 years.

To search LAC holdings of original photographs, follow these easy steps:

- Go to the Basic Archives Search.

- Enter the archival reference number R214-350-0-E in the search box.

- From the Type of material drop-down menu, select Photographic material and then click on Submit. Your search will generate a list of results.

- Select an underlined title to access the full description of a photograph. The descriptive records display images of photographs that have been digitized.

For more information about how to search for photographs at LAC, consult our articles “How to Find Photographs Online” and “How to Search for Images Online.”

If you wish to narrow your search:

- Go to the Archives Advanced Search.

- Select Photographic material from the drop-down menu labelled Type of material

- Use one or a combination of the following options as keywords in the Any Keyword search box:

- Name of the surveyor (e.g., Bridgland, McArthur or Wheeler).

- Year of the survey (must be used along with another keyword to limit search).

- Name of a survey (e.g., Crowsnest Forest Reserve, or Interprovincial Boundary Survey, although these may have taken place over several years, by various surveyors).

- Name of a particular landscape feature, such as mountain peak, river, creek, or valley (often the views are identified by the station/peak they were taken from, rather than by the peak or landscape featured in the photograph).

- Name of the park (Note: The LAC collection does not contain reproductions of the images from Jasper and Banff National Parks).

- Limit your search results by selecting a decade under the label “Date” on the right side of the screen.

For more information about the Project, and to compare the archival images with the repeat photography, visit the Mountain Legacy Project website. To view a sampling of paired photographs, visit our Flickr Set. To view some images of the surveyors, visit our Facebook Album.

Questions or comments? We would love to hear from you!