By Valentina Donato

I have always had an interest in artefacts that share a story. Throughout my undergraduate studies at the University of Ottawa, I surrounded myself with history by working at different museums. As a student working at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), I have learned a remarkable amount about archives and preserving the documentary heritage of Canada. I first found the student archival assistant position through the Federal Student Work Experience Program and thought it would be an engaging summer job. The LAC student program has been full of opportunities to gain experience and learn more about LAC itself and other archives in Ottawa. One of my goals coming into this position was to decide if a career in archives was the right path for me, and I focused on networking and learning as much as possible about municipal and federal archives. Additionally, I had the opportunity to participate in many tours of LAC facilities, as well as other archives like the City of Ottawa Archives and the Canadian War Museum Archive. Not only have the tours been interesting and educational, but I also discovered a new side to historical field I had not known about.

Currently, I am working in the Reappraisal team within the Government Records Initiative Division. In this position, I’ve learned a great deal about how reappraisal plays a critical role in the delivery of LAC’s mandate by supporting discoverability of our holdings and by improving access to government records. One focus of the Reappraisal team is to process backlogged material to identify non-archival records, such as duplicate records, and remove them. In doing so, the team processes archival material and incorporates it into the appropriate place in our collection. Another aim of reappraisal work is to improve the quality of existing records by ensuring that they’re accurately described and documented so that researchers can find what they’re looking for. Both priorities improve how accessible LAC’s government archives are for Canadians and those with an interest in Canadian history. This has been extremely interesting to me because of my interest in making Canada’s history more discoverable and accessible to the public.

As a history student, I believe this is crucial to understanding our past, and I was happily surprised to learn how hands-on my job would be. In the first few months of my summer position, I focused on cataloguing, arranging, and writing descriptions of archival records. It was so rewarding to be able to organize and create finding aids because it allowed for me to aid in making the Government of Canada archives far more accessible to people. I have also had the opportunity to work on the Undiscovered Specialized Media Holdings pilot project with senior archivist Geneviève Morin and archivist Emily Soldera, where I have been looking through boxes of textual documents from the Department of Agriculture. This project has helped me put into practice the skills and knowledge I have acquired through my online assessment of records; I’ve seen first-hand the kinds of files I have been cataloguing.

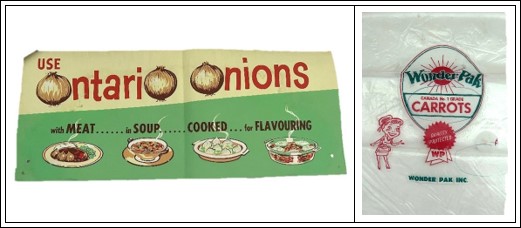

The goal of the Undiscovered Specialized Media Project was to find whether specialized media (such as photographs, posters, or objects) have gone unseen in boxes that were marked as being exclusively textual. The targeted boxes of textual records did reveal many interesting, specialized media finds! To make these finds more discoverable to the public, we tracked our findings and met with the Collection Manager of Government Records, Elise Rowsome. She discussed with us how our new discoveries could be safely stored and preserved.

Fruit and Vegetable Division files, Mikan 134109: RG 17, Volume 4718, File 4718 2-Onions part 1 [Onion print] and RG 17, volume 4717, File 4717 2-carrot part 1 840.3C1 [Carrot packaging]. Note that these files will be temporarily unavailable as work continues ensuring their preservation and rehousing. Image courtesy of the author, Valentina Donato.

Fruits and Vegtable Divison, Mikan 134109, RG 17, Volume 4734 30-1 part 2 [Alcan Aluminum advertisements]. Note that these files will be temporarily unavailable as work continues ensuring their preservation and rehousing. Image courtesy of the author, Valentina Donato.

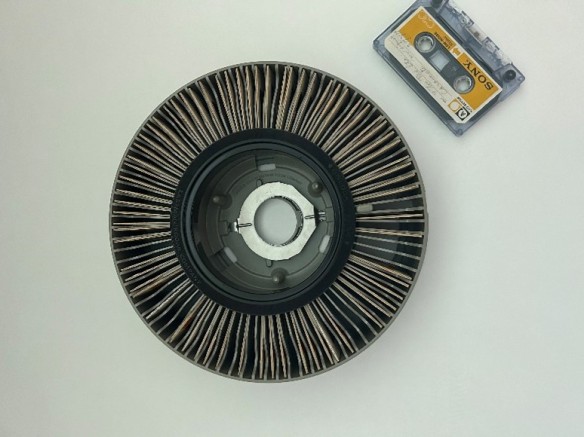

Fredericton Potato Research Centre files, Mikan 206115, Box 50, Slide Show: Fredericton Research Station. Note that these files will be temporarily unavailable as work continues ensuring their preservation and rehousing. Image courtesy of the author, Valentina Donato.

Overall, the student experience at LAC has been extremely rewarding. I am excited to be able to stay on as a part-time student while I complete my studies; I will get to continue my work in reappraisal with arrangement and descriptive work, as well as see the next steps of the Undiscovered Specialized Media Holdings project. Moreover, being in my fourth year of my bachelor’s program, my experience at LAC has opened my eyes to all the potential career paths I want to explore within the heritage and archives field. I am excited to see where this experience takes me and to possibly learn more about underrated root vegetables.

Additional resources

- RG 17 Department of Agriculture fonds

- Fredericton Research and Development Centre Infographic | Directory of scientists and professionals (science.gc.ca)

- The story of agricultural science – agriculture.canada.ca

- Buttery discoveries at Library and Archives Canada by Rebecca Murray, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Breaking ground: 150 years of federal infrastructure in British Columbia – Thompson–Okanagan Region: Summerland Experimental Farm by Caitlin Webster, Library and Archives Canada Blog

Valentina Donato is an Archival Assistant in the Government Record Branch at Library and Archives Canada.