Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Join us every month during 2017 as experts, from LAC, across Canada and even farther afield, provide additional insights on items from the exhibition. Each “guest curator” discusses one item, then adds another to the exhibition—virtually.

Be sure to visit Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? at 395 Wellington Street in Ottawa between June 5, 2017, and March 1, 2018. Admission is free.

The Chewett Globe by W.C. Chewett & Co., ca. 1869

Terrestrial globe by W.C. Chewett & Co. for the Ontario Department of Education, ca. 1869. (AMICUS 41333460)

This globe was one of the first produced in Canada, around the time of Confederation. Designed for use in schools, it was part of a nationalistic push to define and explain the brand new country.

Tell us about yourself

I have travelled extensively for both pleasure and work. I have been to Europe multiple times, and Peru for archaeological digs as a student. I also spent over a year living in Japan as a high school student, and it was an unforgettable experience. The most important lesson I learned was to appreciate and respect things that are different, strange, and sometimes incomprehensible. It taught me to be critical of my biases and the culture I live in, reflexes which promote cohesive living in a multicultural world.

Is there anything else about this item that you feel Canadians should know?

Because of my expertise and love of travel, I have chosen to discuss the Chewett Globe. Maps are a lot of fun! Whenever I travel, I like to look up the country’s world map because they always put their country in the middle of the map. This inevitably causes distortion in the distances between countries and the size of oceans as our planet is spherical. Seeing Canada shrink and stretch has always made me smile and helped me understand how other people see and understand their world, if only a little bit.

Our world is also ever changing, from its physical features, such as rivers and mountains, or abstract constructs, such as names and borders. Therefore, maps must be continuously updated, which allows us to trace history through changes in maps. Maps are critical to my work as an archaeologist. Old city plans might reveal where old buildings once stood or abandoned cemeteries were located but have since been built over and faded from our collective memory. I also must consider how the landscape may have looked like in the past to understand what resources people could access, and what might have inspired them to choose a specific location to camp or imbue meaning onto the landscape through stories and legends.

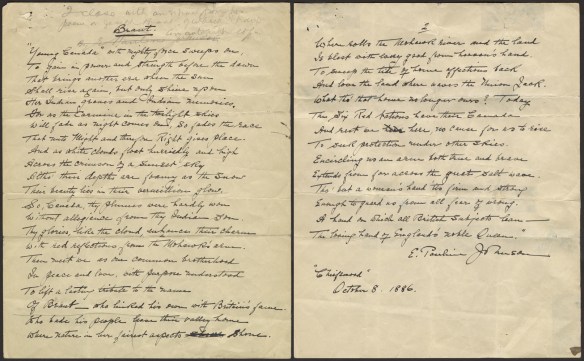

I think Mr. William Cameron Chewett, the person whose company created this globe, would have appreciated these thoughts. Although his profession was printing, his family were involved with mapping Upper Canada. His grandfather, William Chewett, worked as surveyor-general and surveyed most of what is now Ontario, while his father, James Chewett also worked as a surveyor before building many known Toronto buildings. W.C. Chewett and Co. was considered one of Canada’s foremost printing and publishing firms. The firm produced award-winning lithographs between 1862 and 1867, with yearly first place awards, and had a large publication output ranging from periodicals, directories, and the Canadian Almanac, to law and medicine books. In addition, the retail store was a popular social gathering spot. The globe was created in the company’s last year (1869) prior to it being bought and renamed the Copp, Clark and Company.

![A map of Canada West, what is now southern Ontario, with coloured outlines to indicate counties. The legend contains a list of railway stations with their respective distances [to Toronto?].](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/e008318866-v8.jpg?w=584&h=452)

Map of Canada West, engraved and published in the Canadian Almanack for 1865 by W.C. Chewett & Co., Toronto. (MIKAN 3724052)

For Canada’s150th anniversary, I think it is worth reflecting on the changes that have come to pass in the last 150 years, which the Chewett Globe can literally show us. In my lifetime, I observed the creation of the territory of Nunavut and the renaming of various streets in my neighbourhood. What changes have you seen in your life and how did they affect you and your community?

Tell us about another related item that you would like to add to the exhibition

When most people think of maps, they think of geography and political borders, but maps can also be used to illustrate and describe almost anything, including census information, spoken languages, and group affiliations amongst others. To continue the topic, I have selected an 1857 map of North America that shows the regions where various First Nations groups resided at the time. Ideally, if I were to add this map to the exhibition, I would also want to include a modern map of where First Nation groups reside to show the public the momentous changes lived by our fellow citizens to allow them to see these changes as clearly as those they can pick out by comparing the globe to any modern map of Canada.

My other reasoning is a little more selfish. As an anthropologist, I understand and have learned through experience that the best way to appreciate and respect another culture is to learn about it, about the people, and where possible, live in it. Growing up, I had very little exposure to First Nations, their culture and history. Because of this, I never developed much of an appreciation for their culture or interest in learning about them. As an anthropologist and Canadian, I was ashamed of these feelings and sad when fellow Canadians express similar views. For the last few years, I have actively sought to educate myself. By including this piece, I hope to inspire others to appreciate, respect, and learn more about their fellow Canadians. The topic is particularly meaningful on Canada’s milestone year as this is the year we should celebrate coming together and developing stronger bonds, one nation to another.

Map of North America denoting the boundaries and location of various Aboriginal groups. (MIKAN 183842)

Biography

Annabelle Schattmann is a physical anthropologist. She holds a Master of Arts in Anthropology from McMaster University (2015) and a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology from Trent University (2012). She has participated in multiple research projects including a dig in Peru, cemetery excavation in Poland, and research on vitamin C and D deficiencies from various time periods in Canada and Europe.

Annabelle Schattmann is a physical anthropologist. She holds a Master of Arts in Anthropology from McMaster University (2015) and a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology from Trent University (2012). She has participated in multiple research projects including a dig in Peru, cemetery excavation in Poland, and research on vitamin C and D deficiencies from various time periods in Canada and Europe.

Related Resources

McLeod, Donald W. “Chewett, William Cameron.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

![A densely typed page carefully describing the events of the day and mentioning both Captain O’Kelly and Lieutenant Shanklin [sic].](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/e001116905.jpg?w=584&h=355)

![A map of Canada West, what is now southern Ontario, with coloured outlines to indicate counties. The legend contains a list of railway stations with their respective distances [to Toronto?].](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/e008318866-v8.jpg?w=584&h=452)