This blog is part of our Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada series.

By Karyne Holmes

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada is a multilingual and interactive e-book that features hundreds of items in the care of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) through the perspectives of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation staff. The first stages of developing the e-book began in 2018, shortly after I had joined LAC as a researcher for We Are Here: Sharing Stories (WAHSS), LAC’s initiative in researching, digitizing and describing Indigenous-related records to make them more accessible. I was honoured to be invited as one of the co-authors for the e-book and have the task of writing the e-book’s introductory text, “Pidji-ijashig – Anamikàge – Pee-piihtikweek – Tunngasugit – ᑐᙵᓱᒋᑦ – Welcome.” In writing the introduction, I reflected on how finding historical family documents has been personally significant and why the research and access work of WAHSS is so meaningful. I wanted to communicate the value behind projects like the e-book and WAHSS. The introductory message also highlights how the e-book celebrates language knowledge and language reclamation.

Dëne Sųłiné women and children standing in front of a moosehide tanning frame, Christina Lake, Alberta, 1918 (a017946). This photo is featured in “Traditional Caribou and Moosehide Tanning in Northern Dene Communities” by Angela Code.

The Steering Committee on Canada’s Archives recently released a Reconciliation Framework as a response to Call to Action 70 issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. The report acknowledges that the “colonial archival record has significantly contributed to the formation of a Canadian historical narrative that privileges the accomplishments of Eurocentric settler society at the expense of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis identities, experiences, and histories.” A fundamental message of the framework is that archives must respect Indigenous peoples’ intellectual sovereignty over materials created by or about them, and they must integrate Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, languages, histories, place names and interpretations into Indigenous-related archives.

The framework outlines ways that we can incorporate reconciliation into archival practices that reflect the work that has started at LAC. Our collaborative Nations to Nations publication is a valuable educational resource that shows the importance of re-contextualizing archival records to bring awareness to the diversity within First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation perspectives and lived experiences.

“Pidji-ijashig – Anamikàge – Pee-piihtikweek – Tunngasugit – ᑐᙵᓱᒋᑦ – Welcome” in Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada

To read the following text in Anishinabemowin, see the e-book. Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada is free of charge and can be downloaded from Apple Books (iBooks format) or from LAC’s website (EPUB format). An online version can be viewed on a desktop, tablet or mobile web browser without requiring a plug-in.

Archives and library collections provide a glimpse into the lives and experiences of our ancestors. This is true for all people, but they have special significance to Indigenous peoples. Ongoing colonial policies and actions have separated our families, thus cutting our connections and access to culture, community, knowledge and stories. Archival records and publications can facilitate the discovery of family and community history. They can also ignite memories and restore knowledge. For many, these have been partially lost through the residential school era and the ongoing forced removal of Indigenous children from their families. Historical records can recover missing pieces and unearth new information about our personal and community histories. They can allow us to share our stories with the world, in our own words.

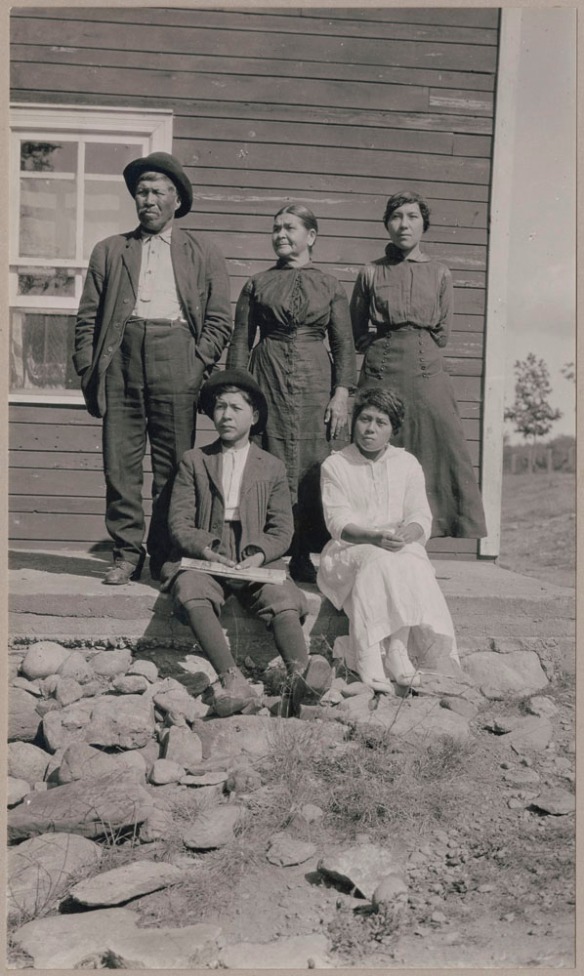

Michel Wakegijig and his family outside their home at Wiikwemkoong First Nation, ca. 1916 (e011310537-040_s1).

Although the value held within historical records is recognized, the majority of documents at Library and Archives Canada (LAC) were created, collected and interpreted through a colonial lens. As a result, many records pertaining to Indigenous communities are marred by missing details and inaccurate portrayals, and they are often described with a focus on what the record creator perceived to be of interest and importance. It is crucial to apply Indigenous insight, to contextualize and interpret records that pertain to First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation.

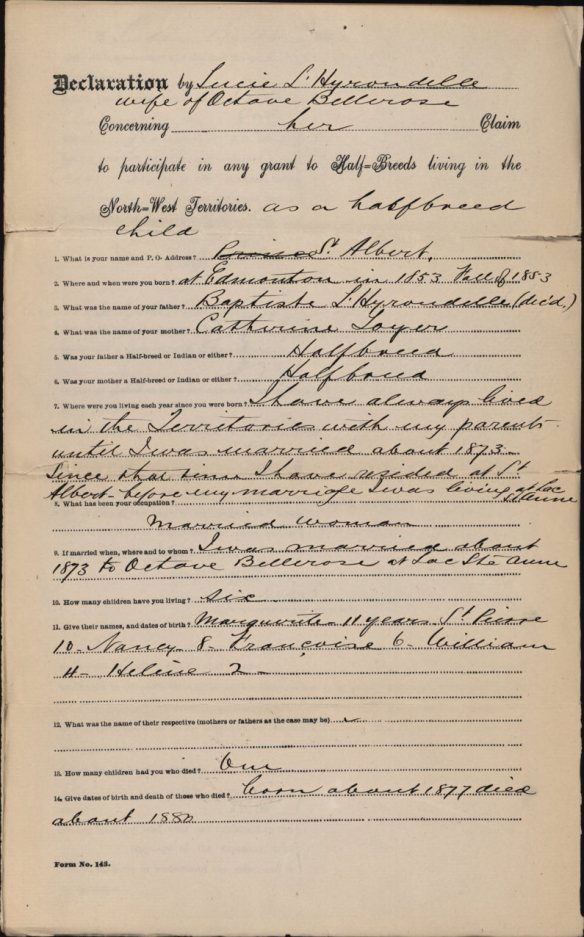

Page from the declaration of Lucie Bellerose on her scrip application, signed at St. Albert in 1885. Digitized scrip records contain biographical information on Métis Nation ancestors (e011358921).

Current initiatives at LAC are working toward prioritizing First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation stewardship of Indigenous content. We Are Here: Sharing Stories is modifying archival record descriptions through a decolonizing lens. We are incorporating place names, community names, persons’ names and cultural terms into descriptions so that they accurately represent the record. Listen, Hear Our Voices is providing support to communities who wish to control and preserve the language-specific materials created and housed within their own communities.

Young Inuk woman from Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset) in red qilapaaq (straight-hemmed) style parka and kamiik (boots) with polar bears embroidered on the duffel liners, Iqaluit, Nunavut (formerly Frobisher Bay, Northwest Territories), 1968 (e011212600). The description of this photo was provided through the We Are Here: Sharing Stories project.

This e-book features a collection of archival documents and published material held at LAC that was selected by LAC team members who identify as First Nations, Inuk or Métis Nation. The records we chose are drawn from transcripts, photographs, maps, audiovisual material and publications. They highlight the importance of our cultural identity, and they reflect personal experiences in learning and knowing about our own histories. The essays feature different voices, multiple perspectives and personal interpretations of records.

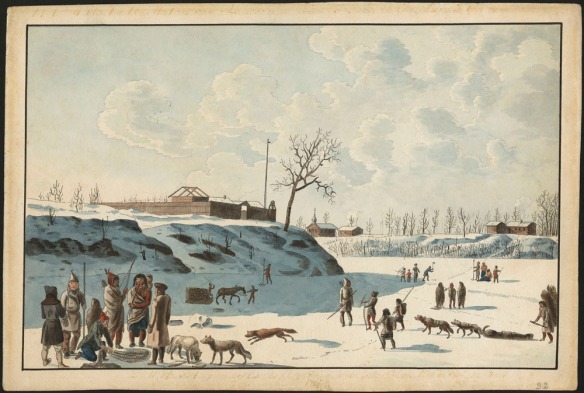

Winter fishing on the Assiniboine and Red rivers, with a fort in the background (present-day Winnipeg), Manitoba, 1821 (e011161354). This artwork is featured in “Fishing on the Red River for 3,000 Years” by William Benoit.

Where possible, translations are provided in the Indigenous language spoken by the people represented in each essay. For Indigenous peoples, language is inextricably tied to culture. Indigenous languages are exceptionally descriptive of objects, experience and emotion, which cannot be wholly explained or translated into English or French. Languages of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation have been learned intergenerationally through stories, songs and land-based experiences. Language is largely influenced by the physical landscape and its resources; these have shaped Indigenous vocabularies that hold unique representations and values distinct to each culture. First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation across Canada are reclaiming their languages to connect to their history, to secure cultural continuity, and to honour their ancestors by knowing the languages through which they understood the world.

We respect the wishes of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation about how they would like their languages and identities expressed in English and French. This may mean that some conventional rules of grammar are not applied.

Additional resources

- “Archives as resources for revitalizing First Nations languages” by Karyne Holmes, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- “Exploring Indigenous peoples’ histories in a multilingual e-book—Part 1” by Beth Greenhorn in collaboration with Tom Thompson, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- “Exploring Indigenous peoples’ histories in a multilingual e-book—Part 2” by Beth Greenhorn in collaboration with Tom Thompson, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives: We Are Here: Sharing Stories, Library and Archives Canada

- Indigenous Heritage Action Plan, Library and Archives Canada

Karyne Holmes is a curator in the Exhibitions and Loans Division and was an archivist for We Are Here: Sharing Stories, an initiative to digitize and describe Indigenous content at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg?w=584&h=365)