The Library and Archives Canada (LAC) Discover Blog has hit an important milestone! We have published 1,000 blog posts! For the past eight years, the blog has showcased our amazing documentary heritage collection, let researchers know what we are working on, and answered frequently asked questions.

To celebrate this momentous occasion, we are looking back at some of our most popular blog posts.

1940 National Registration File

Sample of a questionnaire for women, courtesy of Statistics Canada.

Year after year, this early blog post has consistently been at the top of our list of views and comments. It is not surprising that a genealogy themed post took the top place; what is surprising is that the 1940 National Registration File is not held at LAC, but can be found at Statistics Canada. Either way, it is a great resource and very useful to genealogists across the country.

Want to read more blog posts about genealogy at LAC? Try the post, Top three genealogy questions.

Do you have Indigenous ancestry? The census might tell you

Indigenous man and woman [Alfred and Therese Billette] seated on the grass with two children [Rose and Gordon] outside their tent (e010999168).

Want to read more blog posts on how to research your Indigenous heritage? Try one of these posts, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development records: Estate files or The Inuit: Disc numbers and Project Surname.

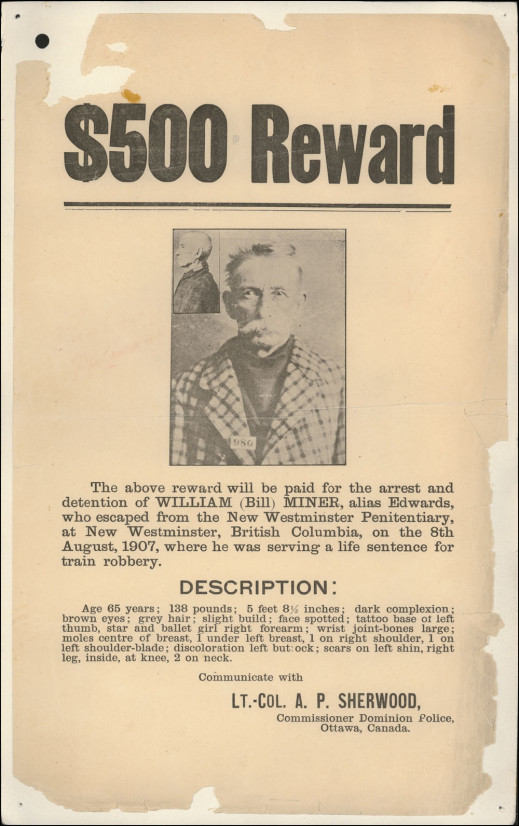

The Grey Fox: Legendary train robber and prison escapee Bill Miner

Reward notice for the recapture of Bill Miner that was sent to police departments, publications and private detective agencies (e011201060-210-v8).

This exciting post tells the story of Bill Miner, who was nicknamed “The Grey Fox” and “The Gentleman Bandit.” Bill Miner was a legendary criminal on both sides of the Canada–U.S. border. Although he committed dozens of robberies and escaped from multiple prisons, many saw him as a generous folk hero who targeted exploitative corporations only. LAC holds many documents, publications, sound and video recordings, and other materials relating to Miner, and hundreds of these documents are now available on our website as a Co-Lab crowdsourcing challenge.

Want to learn more about records from the B.C. Penitentiary system? Try the post, British Columbia Penitentiary’s Goose Island: Help is 20 km away, or 9 to 17 hours as the pigeon flies.

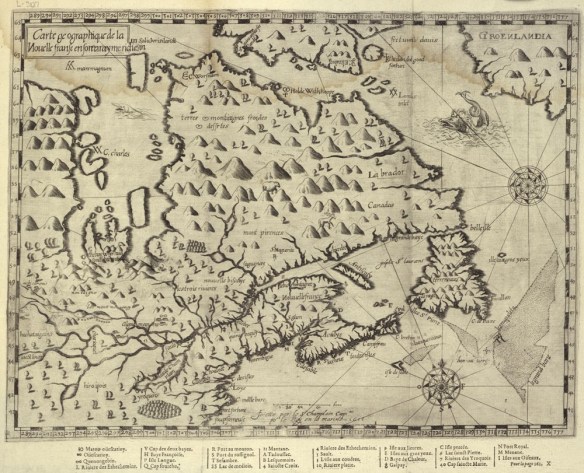

Samuel de Champlain’s General Maps of New France

Carte geographique de la Nouelle Franse en son vray meridiein Faictte par le Sr. Champlain, Cappine. por le Roy en la marine—1613 (in french only) (e010764734).

This popular 2013 post combines two aspects of Canadian interest: cartography and explorers! This article gives an overview of Champlain’s maps of New France held in the LAC collection. Also included in the post is a “suggested reading list” so researchers can learn more about Champlain’s cartography and travels.

Want to read more about the history of New France? Try the post, Jean Talon, Intendant of New France, 1665-1672.

Journey to Red River 1821—Peter Rindisbacher

Extremely wearisome journeys at the portages [1821] (e008299434).

Want to learn more about Peter Rindisbacher? Try the podcast, Peter Rindisbacher: Beauty by commission.

Unveiling of a plaque commemorating the five Alberta women whose efforts resulted in the Persons Case, which established the rights of women to hold public office in Canada (c054523).

This blog post illuminates the history of women’s fight for political equality in Canada. The Persons Case, a constitutional ruling that established the right of women to be appointed to the Senate, began in 1916 when Emily F. Murphy was appointed as the first female police magistrate in the British Empire. Undermining her authority, lawyers challenged her position as illegal on the grounds that a woman was not considered to be a person under the British North America Act, and therefore she was unable to act as magistrate. Murphy enlisted the help of Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie Mooney McClung, Louise Crummy McKinney, and Irene Marryat Parlby—now known as the “Famous Five”—who were engaged politically and championed equal rights for women.

Want to learn more about women’s rights throughout Canada’s history? Try the post, A greater sisterhood: the women’s rights struggle in Canada.

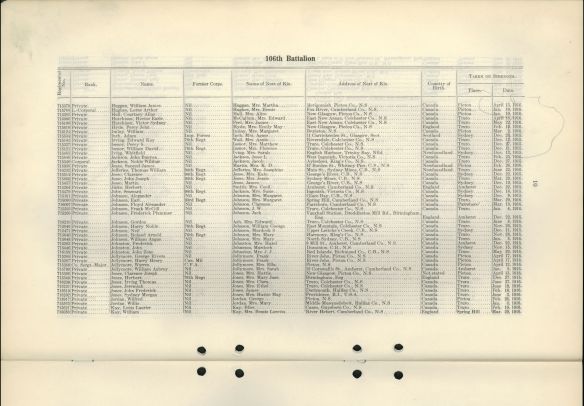

The Canadian Expeditionary Force Digitization Project is Complete!

A page from Allan “Scotty” Davidson’s digitized service file describes how he was killed in action (CEF 280738).

The last post on our list is an impressive one! The blog announcing the completion of LAC’s 5-year project to digitize all 622,290 files of soldiers who enlisted in the First World War was well-received by many researchers.

Want to learn more about how the Canadian Expeditionary Force digitization project started? Try the post, Current status of the digitization of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Personnel service files.

We hope you enjoyed our trip down memory lane. You may also be interested in blogs about Canada’s zombie army, the Polysar plant, LAC’s music collection, historical French measurement standards, or the iconic posters from the Empire Marketing Board.