By R.L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi

When asked to name one of Canada’s fundamental democratic institutions, how many people would immediately say “Library and Archives Canada”? Yet, a nation’s archives preserves in perpetuity the evidence of how we are governed.

From the story of Japanese Canadian Redress, we can learn how records held by Library and Archives Canada (LAC)—combined with crucial citizen activism making use of these records—have contributed to holding the federal government accountable for now universally condemned actions.

From silence to a movement

When the Second World War ended, devastated survivors buried their trauma out of necessity in order to focus on rebuilding their lives. Silence enveloped the Japanese Canadian community.

However, in the late 1970s and early 80s, at small, private, social gatherings where survivors felt safe to share their wartime experiences, a grassroots redress movement was born.

The Redress Agreement states that between 1941 and 1949, “Canadians of Japanese ancestry, the majority of whom were citizens, suffered unprecedented actions taken by the Government of Canada against their community.” These actions were disenfranchisement, detention in internment camps, confiscation and sale of private and community property, deportation, and restriction of movement, which continued until 1949. These actions were taken by the Government of Canada, influenced by discriminatory attitudes against an entire community based solely on the racial origin of its members.

Sutekichi Miyagawa and his four children, Kazuko, Mitsuko, Michio and Yoshiko, in front of his grocery store, the Davie Confectionary, Vancouver, BC, March 1933 (a103544)

Arrival of Japanese Canadian internees at Slocan City, BC, 1942. Credit: Tak Toyata (c047396)

Citizen activism and declassified government documents

In 1981, Ann Gomer Sunahara researched newly declassified Government of Canada records made accessible by the then Public Archives of Canada. Sunahara’s book The Politics of Racism documented the virtually unquestioned, destructive decision-making with respect to the Japanese Canadian community of Prime Minister Mackenzie King, his Cabinet, and certain influential civil servants.

Rt. Hon. W.L. Mackenzie King (right) and Mr. Norman Robertson (left) attending the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference, London, England, May 1, 1944. It was during this time period that Norman Robertson, Under Secretary of State for External Affairs, and his special assistant Gordon Robertson (no relation) developed the plan which resulted in the deportation of 3,964 Japanese Canadians to Japan in 1946. (c015134)

The National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC), which came to represent the views of the community concerning redress, astutely recognized the critical importance of having access to government documents of the 1940s, which could serve as primary evidence of government wrongdoing.

On December 4, 1984, The New Canadian, a Japanese Canadian newspaper, reported that the NAJC had “spent months digging through government archives” to produce a report entitled Democracy Betrayed. The report’s executive summary stated: “The government claimed that the denial of the civil and human rights [of Japanese Canadians] was necessary because of security. [G]overnment documents show this claim to be completely false.”

Citizen activism and the records of the Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property

In 1942, all Japanese Canadians over the age of 15 were forced by the government to declare their financial assets to a representative from the federal Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property. Custodian “JP” forms containing a detailed listing of internee property formed the nucleus of 17,135 Japanese Canadian case files.

To further negotiations with the Canadian government to obtain an agreement, the NAJC needed a credible, verifiable estimate of the economic losses suffered by the Japanese Canadians. On May 16, 1985, the NAJC announced that the accounting firm Price Waterhouse had agreed to undertake such a study, which would culminate in the publication of Economic Losses of Japanese Canadians after 1941: a study.

Sampling Custodian records in 1985

A team of Ottawa researchers, primarily from the Japanese Canadian community, was engaged by Bob Elton of Price Waterhouse to statistically sample 15,630 surviving Custodian case files, held by the then Public Archives of Canada. These government case files contained personal information that was protected under the Privacy Act (RSC, 1985, cP-21). However, under 8(2)j of the Act, the files were made accessible to the team for what the Act deems “research and statistical purposes.”

On September 20, 1985, the Ottawa Citizen newspaper reported Art Miki, then president of the NAJC, saying that the “Custodian (case) files are the most valuable raw material for the economic loss study because they meticulously document each transaction whether it was the sale of a farm, or a fish[ing] boat, a house or a car.”

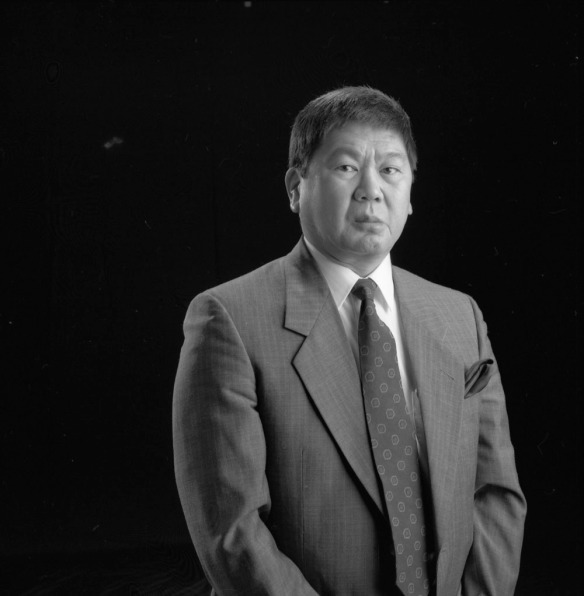

Art Miki, educator, human rights activist, and president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) from 1984 to 1992. Miki was chief strategist and negotiator during the Redress Campaign, which culminated on September 22, 1988, with the signing of the Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement between the NAJC and the Government of Canada. In 1991 he received the Order of Canada. Photographer Andrew Danson (e010944697)

Citizen activism: Molly and Akira Watanabe

In the final sampling, 1,482 case files were reviewed. It was grueling, painstaking work. Some researchers were unable to continue because of nausea and eyestrain induced by hours spent pouring over microform images, some of very poor quality.

A superlative example of citizen activism is the dedication of Ottawa researchers Akira Watanabe, Chairman of the Ottawa Redress Committee, and his wife Molly. With several hundred files still unsampled, dwindling numbers of researchers and only four weeks remaining to do the work, the Watanabes went to Public Archives Canada after work for twenty evenings. Molly Watanabe died in 2007.

On May 8, 1986, the study was released to the public. Price Waterhouse estimated economic losses for the Japanese Canadian community at $443 million (in 1986 dollars).

Archival records alone do not protect human rights

Documents sitting in a cardboard box on a shelf, or microfilm sitting in cannister drawers, cannot protect human rights—people do. Japanese Canadian Redress showed Canadians that it takes dedicated activism to locate and use archival records.

Archival government and private records from the 1940s preserved by LAC and used by citizen activists were critical in building the Japanese Canadian case for Redress. By preserving the records that hold our government accountable in the face of injustice, LAC continues to be one of our country’s key fundamental democratic institutions.

R.L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi is an archivist in the Society, Employment, Indigenous and Governmental Affairs Section, Government Archives Division, at Library and Archives Canada.