By Evan Dalrymple

Many people know about the Friends of the Ottawa Public Library and their book stores across Ottawa, but the Friends of Library and Archives Canada (FLAC) and its Cubby bookshop is one of 395 Wellington’s best kept secrets. For those who know, it’s a treasure!

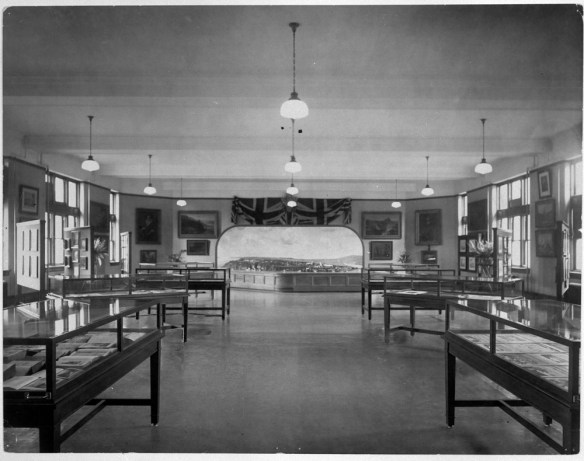

The National Library and Friends’ logo on the bookshop. This logo is derived from the original mural by Alfred Pellan, titled La Connaissance / Knowledge. This mural is in the Pellan Room within the Public Archives and National Library Building at 395 Wellington. (MIKAN 4932244).

The Cubby is open every Tuesday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. in room 185 on the main floor of the Public Archives and National Library Building. I urge you to visit the Cubby in person or online to find the next addition to your personal library.

History of the Friends in Ottawa

In the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, Friends associations flourished in galleries, libraries, archives and Museums in Canada. Particularly in Ottawa, Friends’ associations earliest examples are the National Gallery of Canada (1958), the Canadian War Museum (1988) and the Ottawa Public Library (OPL) Main Branch (1982), which is the most well known of the associations.

The Friends of National Library of Canada was founded in 1991 by Marianne Scott, a former National Librarian of Canada (1984–1999) and the current president of FLAC.

In 2003, The Friends of the National Library of Canada and the Friends of the National Archives of Canada formed one single Friends organization—The Friends of Library and Archives Canada—in anticipation of the fusion of the National Archives with the National Library, which occurred in May 2004 with the official proclamation of the Library and Archives Canada Act.

The newsletter of the Friends of the National Library, “A note among friends,” published between 1992 and 2008, clearly demonstrate how book sales, boutiques and antiquarian book auctions have been monumentally successful ways to reach out to the larger community and to develop the National Library collection.

A note among friends and The Friends of the National Library of Canada pamphlets (OCLC 1082162430 & OCLC 61127762).

Encouraging donations and gifts of treasures and fundraising for special acquisitions is central to the Friend’s constitution.

The Friends of National Archives organization also formed in 1995 under the leadership of Jean-Pierre Wallot (1985–1997), with their own newsletter “Between friends.” The National Archives also had a boutique, but less is known about their activities.

FLAC’s Big Book Sales and antiquarian book auctions

Many perhaps have heard of OPL’s yearly Mammoth Book Sales (MBS), but did you know that FLAC once hosted its own enormously successful “Big Book Sales”? These book sales, hosted alongside the Friends organizations of the Nepean Public Library, the Kanata Public Library, the Cumberland Public Library and local booksellers, have been a success in Ottawa for well over a decade. Even before consolidating in 2003 to create the Friends of the Ottawa Public Library Association, Friends organizations were thriving in various public libraries across Ottawa.

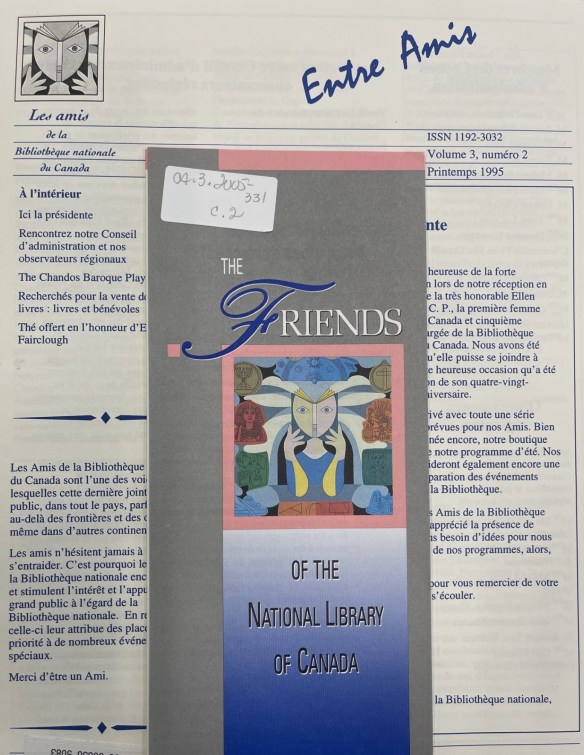

The first sale at St. Laurent mall from A note among friends, 1995, Winter, Volume 4, No. 1. (OCLC 1082162430).

The inaugural Big Book Sale took place September 23–25, 1995 at the St. Laurent Shopping Centre. According to the book sale committee, the sale by all measures was a resounding success. It raised $17,164.49, and an additional 423 books were donated to the National Library. In subsequent years, the Friends often doubled or tripled this amount.

FLAC initiated its first antiquarian book auction in the winter of 2000, continuing it until about 2008. As is the case today, all Canadian book donations are set aside and reviewed by a National Library staff member before they become part of the library collection. The Friends earmarked their rarer books for antiquarian book auctions. Today, FLAC features select books on their online store, inviting bids that are too good to pass up, so don’t miss out!

A history of the Cubby

Initially known as the “Friends Boutique,” the Cubby started in 1993 as a pop-up store situated in the sunken lobby of the Public Archives and National Library building. The Boutique was open from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. daily from June 1st to the end of August.

Thank you for being a Friend! The Fall 1996 catalogue, which featured the new Friends’ Boutique selling interesting merchandise (OCLC 1082162430).

The Boutique was staffed by two volunteers who also provided tours of the National Library in English and French, and it offered a remarkable selection of items, including postcards, posters, CDs from celebrated Canadian Musicians, as well as magnetic tapes from the National Library Music Division. T-shirts and sweatshirts emblazoned with “WOW” for Wellington Street West became especially popular. Many of the cherished items remain available at the Cubby today. Additionally, membership cards to FLAC are on offer—consider joining today!

In 2014, the Friends’ book sales division relocated to room 185 at 395 Wellington, attached to the Morley Callaghan meeting room. The basement now houses an extensive storage area for sorting a vast collection of books and hosts an office where Library and Archives Canada (LAC) staff can meticulously assess each donation.

By 2017 the FLAC bookstore, affectionately known as the Cubby, made its debut. The Cubby offered gently used books, with proceeds supporting the acquisitions of Canadiana for LAC. The store is open three days a week, bolstering its presence by running an annual big book sale and by opening its doors to the public on special occasions, including Canada Day.

Come 2019, the Cubby had enlisted the aid of over ten volunteers and succeeded in raising $3000, contributing to the purchase of significant works such as the rare edition of “Adventures of a Field Mouse,” by Catharine Parr Traill, and Leacock’s best-known book, “Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town” —the American version in the original dust jacket.

The pandemic in 2020 necessitated the closure of the Cubby, yet in response, FLAC pivoted to an online version of its antiquarian book sales of the past. So bid away!

Treasures found at the Cubby

The second and third laws of library science proposed by S.R. Ranganathan in 1931 (OCLC 1007655699)—that every reader has a book, and every book its reader—are ideas that resonate with my experiences at the Cubby.

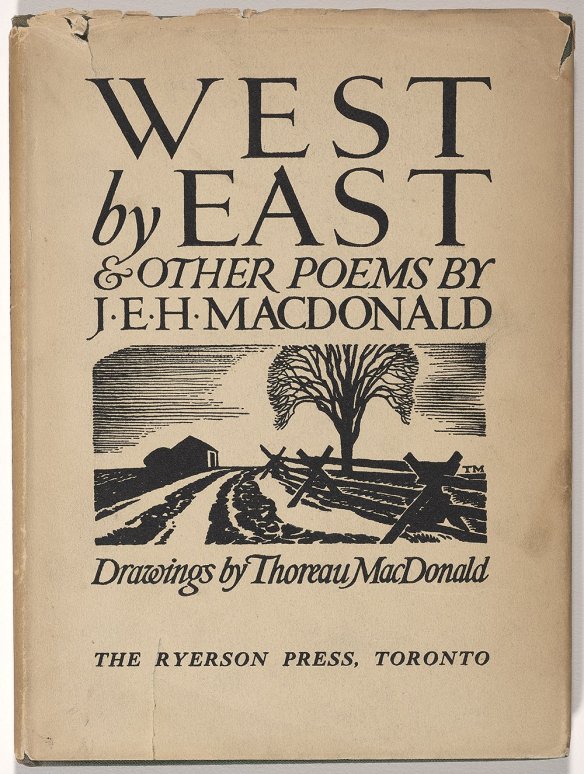

In 2019, I visited an exhibit at the National Gallery of Canada which contained the Archives of Thoreau and J. E. H. MacDonald collection and the book West by East and other Poems by J. E. H. Macdonald (OCLC 11487298). This Ryerson Press book, enriched by Thoreau MacDonald’s drawings and the original dust jacket, are images that have etched themselves in my memory.

To my delight, I recently managed to acquire a rare copy—the first of five hundred pulled—through negotiation on the Cubby’s online platform!

My copy of West by East by J.E.H MacDonald (OCLC 11487298) is one of the first five hundred copies produced.

Photo credit: J.E.H. MacDonald, West by East and other poems, with illustration by Thoreau MacDonald. Toronto 1933. National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives Photo: National Gallery of Canada

I have since discovered a treasure trove of Thoreau MacDonald-designed books at the Cubby store. These books are all in very good condition with original dust jackets from the 1930s from Ryerson Press Books and adorned with illustrations by Thoreau Macdonald.

First, I discovered a very handsome copy of Thoreau MacDonald: A Catalogue of Design and Illustration. My copy is signed by the humble compiler, Richard Landon, and is noted for its significance in Canadian book illustration history. Richard Landon was the head of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, which has been referred to as “the house that Richard Built.”

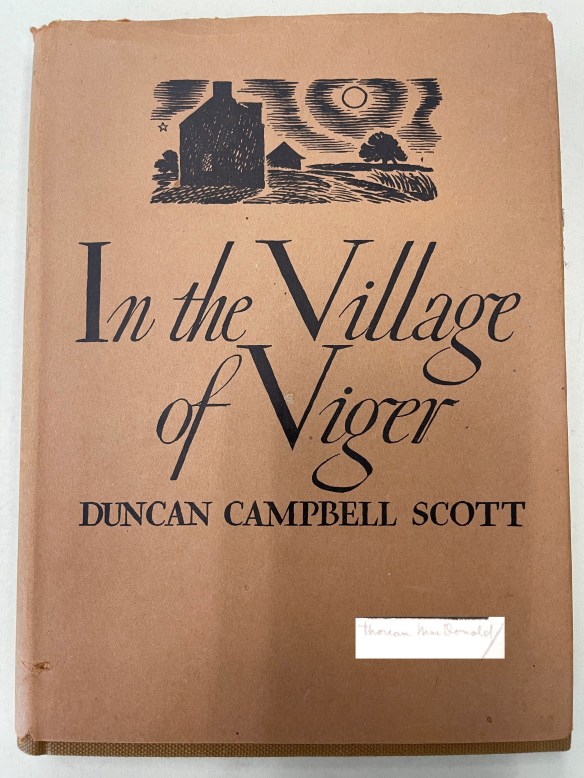

Since armed with this catalogue of book design and illustration, I also located two other treasures by the Confederation poets Duncan Campbell Scott (1862–1947) and Sir Charles George Douglas Roberts. Both books were inscribed and signed by the authors and had rare ephemera placed within. Could it be that these books were waiting on the cart of the Cubby for me?

In the Village of Viger (OCLC 3634059), by Duncan Campbell Scott, was designed and signed by Thoreau MacDonald. Duncan Campbell Scott was a poet and a controversial civil servant, leaving a complicated legacy for Canadians to consider regarding his part as an architect of the Residential Schools.

In the Village of Viger (OCLC 3634059) by Duncan Campbell Scott, a Confederation poet and an architect of the Residential Schools in Canada. My copy from the Cubby was signed by Thoreau MacDonald. Photo courtesy of the author, Evan Dalrymple.

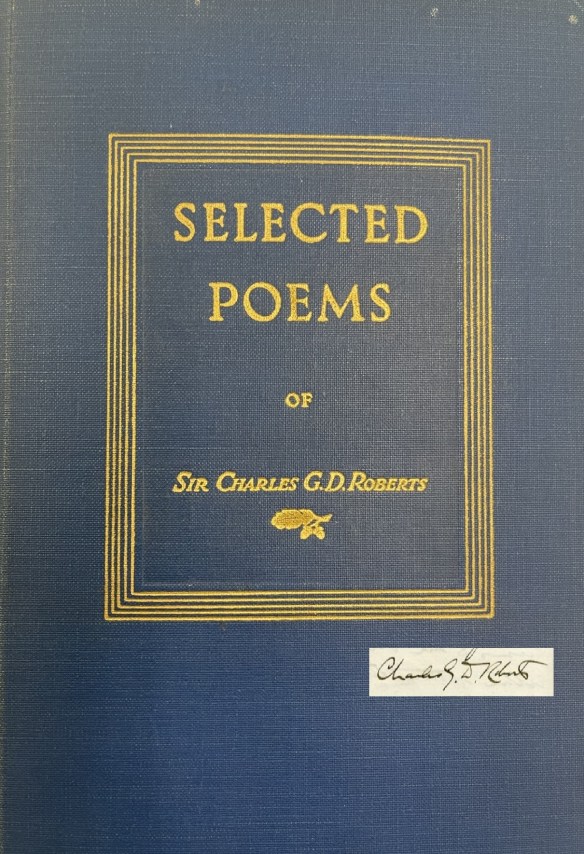

My next find was the Selected Poems of Sir Charles G. D. Roberts (OCLC 27780946). This book was personally inscribed, and to my astonishment, I found various pieces of ephemera, including a signed mimeograph of his poem “Those Perish, Those Endure” about the Spanish Civil War and a signed article from the Dalhousie Review in April 1930, “More Reminisces About Bliss Carman”. Bliss Carman was Charles Robert’s cousin and a prolific Confederation Poet.

Selected Poems of Sir Charles G. D. Roberts (OCLC 27780946). My copy from the Cubby was signed and full of ephemera. Photo courtesy of the author, Evan Dalrymple.

The next chapter of the Cubby/ Le Recoin

At Ādisōke, a joint facility shared by the Ottawa Public Library and Library and Archives Canada, construction is well under way. Ādisōke is Anishinaabemowin word that means “storytelling,” and it promises to be a hub for our community. The question is—what will become of our Cubby?

Will it be a charming pop-up as from the bygone days, with “Big Book Sales” and auctions, or will it forge a new path? The fusion of the Ottawa Public Library and Library and Archives Canada may recreate the collaborative spirit we remember.

As we turn the page to the next chapter for the Friends and discover the new gathering space that will emerge at Ādisōke, we anticipate the new treasures that await us.

In closing, find your own treasures at the Cubby Big Book sale that will occur during LAC’s Doors Open Ottawa event on June 1 and 2, 2024. This will also mark 31 years of selling books—see you all at the Cubby!

To contact the Cubby, email Amis-friends@bac-lac.gc.ca or call 613-992-8304.

Further reading

- Abley, Mark. 2013. Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott. Madeira Park, BC: Douglas & McIntyre (OCLC 856726449).

- Landon, Richard, Marie Elena Korey, and Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. 2014. A Long Way from the Armstrong Beer Parlour: A Life in Rare Books: Essays. Toronto, Ontario: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (OCLC 890957110).

- From our rare book vault: What makes a book rare?, Library and Archives Canada Blog

Evan Dalrymple is a Reference Librarian for the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada, located at 395 Wellington.