This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

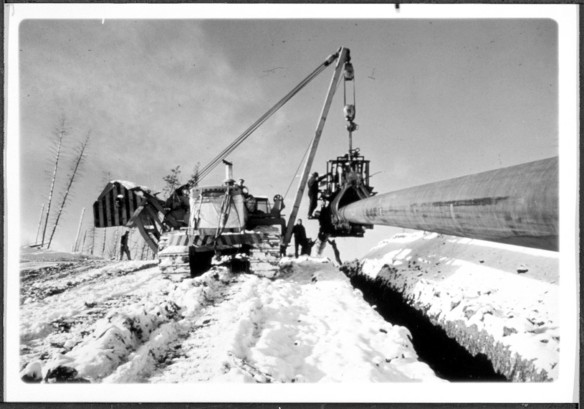

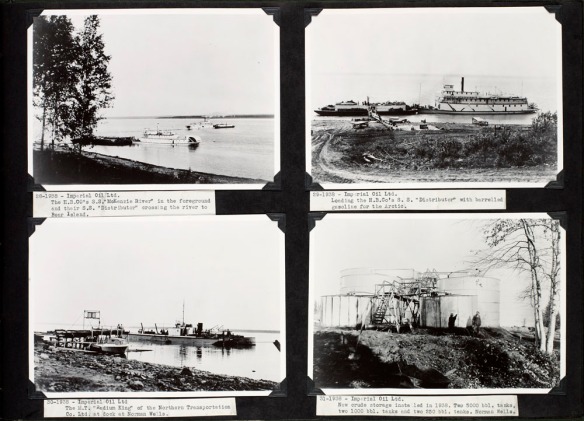

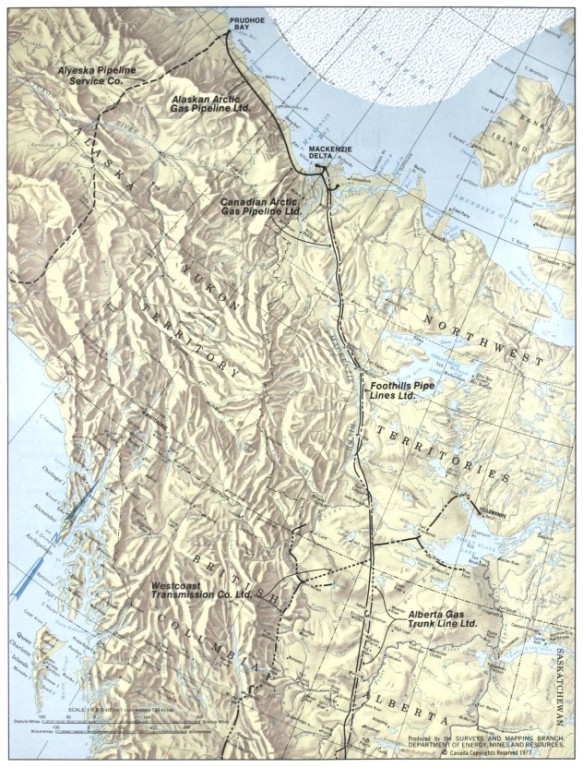

The Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry (MVPI), also known as the Berger Inquiry, was enacted fifty years ago in 1974 by the Canadian government. The purpose of the Inquiry was to investigate the potential impacts of the pipeline and report findings, which would be followed by appropriate actions. The final report (Volume One and Volume Two) was published in 1977. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) holds the original collection of Inquiry records, which are managed by the Government Archives Division.

This is part two of a three-part series on the MVPI. This blog will highlight two individuals who were central to the thoroughness of the Inquiry process as well as provide additional search methods for Inquiry records.

Part one presented a glimpse of the people and land of the Yukon and Northwest Territories (NWT) who would be affected by the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, along with a narrative of events that led up to the enactment of the Inquiry by the Canadian government. The final blog, part three, will focus on more specific searches for the records.

Commissioner Thomas R. Berger and interpreter and Inuk broadcaster Abraham Okpik

The Inquiry to study the potential environmental and socio-economic impacts of the proposed gas pipeline project was headed by Justice Thomas R. Berger. A former Justice of the B.C. Supreme Court, he possessed legal experience in First Nations issues. He had recently represented the Nisga’a and argued the Aboriginal title case Calder et al. v. Attorney-General of British Columbia, [1973] S.C.R. 313. This led to the 1973 Calder decision by the Supreme Court of Canada, which recognized that Aboriginal title to land existed prior to colonization and that Nisga’a land title had never been extinguished.

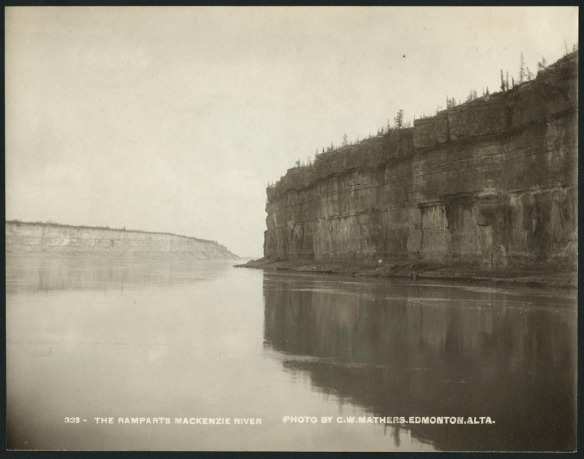

Abraham “Abe” Okpik, who was born in the Mackenzie River Delta, was an interpreter for the Inquiry in 1974. He also served as a linguistic representative for CBC to report on the Inquiry hearings. Okpik’s language skills combined with his life experiences were crucial for the Inquiry to establish communication and understanding with people from different Arctic communities.

In 1965, Okpik was the first Inuk to sit on the Council of the Northwest Territories (NWT). His legal surname at the time was “W3-554” due to the Canadian government system of using disc numbers to identify people in the North. Okpik eventually chose his new surname and was selected to head Project Surname in 1970. Under this project, Okpik visited Inuit camps and communities in northern Quebec and the NWT to record the surnames people wanted to replace their identification numbers. In 1976, Okpik was awarded the Order of Canada in recognition of his contributions to the preservation of the Inuit way of life and his work on the Berger Inquiry.

Abe Okpik, 1962 (e011212361).

Conclusions of the Inquiry

Commissioner Berger summed up his thoughts in his November 1978 article on the MVPI with comments on industrialization, energy waste, the creation of wilderness parks and whale sanctuaries, and the need for humanity to reflect on its use of resources. He recognized the North as the last frontier and that the pristine and undeveloped areas were critical habitat for many creatures and their continued survival. He writes that in his MVPI report there are two sets of conflicting attitudes and values: “the increasing power of our technology, the consumption of natural resources and the impact of rapid change” versus “the growth of ecological awareness, and a growing concern for wilderness, wildlife resources and environmental legislation.”

The Inquiry concluded that a pipeline along the Mackenzie Valley to Alberta was feasible, but that it should only proceed after further study and after the settlement of Indigenous land claims. Based on this conclusion, a ten-year moratorium on construction was declared.

Voices speaking for land and life

The Inquiry was groundbreaking in its implementation of direct consultation that included hearings with the people of the communities that would be impacted by the project. They were aware that the pipeline would bring change and affect their relationship with the animals and the land. They spoke of their way of life and of knowledge that had been passed to them. Audio recordings of these oral testimonials are culturally invaluable. Their knowledge at that specific moment in time is preserved and available for future generations to hear.

Reindeer taking part in the Canadian Reindeer Project crossing the Mackenzie River, 1936 (a135777).

Fred Betsina, a 35-year-old Dene from Detah Village, NWT, explained at the Detah Community Hearing why he did not want a pipeline. He told how he knew from trapping and hunting caribou that they were not able to jump over a 48-inch pipe—that they can’t jump higher than 12 inches, so instead they need to go around whatever is blocking their path. He stated that he wanted to see the land settlement claims settled before he saw a pipeline. His last comment was, “… us Indians. We got no money in the bank, nothing … The only money we got in the bank is the cash out in the bush … We get our meat from there, and fish is the cash … that’s what you call a bank here…” He spoke for the wildlife, for his people and for his family’s needs.

The gathering of people from distantly located communities also presented opportunities to forge new friendships and strengthen alliances. The Inquiry gave a space for informal discussion on economic and political subjects.

Discovering MVPI collection materials

The records of the MVPI were transferred to the public archives of Canada in February 1978. All MVPI records are open to the public for research purposes, though not all records are digitally available.

Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry (multiple media) R216-165-X-E, RG126. Date: 1970–1977 (MIKAN 383).

Additional sources and tips for records searches

The following is to provide more specific guidance on searching for MVPI records in Collection Search.

On the Record Information Page for the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry (Reference: R216-165-X-E, RG126), there are three sections: Record information – Brief, Record information – Details, and Ordering and viewing options.

If you open the second section (Record information – Details), you will find a link titled, “View lower-level description(s).” Clicking on that link will open the three main series of records: Transcripts of proceedings and testimony, Exhibits presented to the Inquiry, and Operational and administrative records

Opening one of three series of records above will link to the Record Information Page for that series. To view the lower-level records within each series, open the “Record information – Details” section and click on the “View lower-level description(s)” link.

In Transcripts of proceedings and testimony (R216-3841-6-E, RG126), you will find two lower-level descriptions:

- Transcripts of community hearings (R216-169-7-E, RG126)

- Transcripts of formal hearings (R216-172-7-E, RG126)

In Exhibits presented to the Inquiry (R216-3840-4-E, RG126), you will find four lower-level descriptions:

- Vancouver hearings exhibits (R216-173-9-E, RG126)

- Community hearings exhibits (R216-168-5-E, RG126)

- Submissions of the merits of the Inquiry (R216-166-1-E, RG126)

- Formal hearings exhibits (R216-171-5-E, RG126)

In Operational and administrative records (R216-174-0-E, RG126), you will find six lower-level descriptions:

- Committee for Original People’s Entitlement (R216-174-0-E, RG126, Volume number: 72)

- Correspondence – General (R216-174-0-E, RG126, Volume number: 72)

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (R216-174-0-E, RG126, Volume number: 72)

- Canadian Arctic Gas Pipelines LTD (R216-174-0-E, RG126, Volume number: 72)

- Canadian Arctic Resources Committee – Northern Assessment Group (R216-174-0-E, RG126, Volume number: 72)

- Canadian Arctic Resources Committee (R216-174-0-E, RG126, Volume number: 72)

*Please note not all MVPI records are available online digitally. MVPI records that are not digitally accessible online will have to be requested and accessed onsite at LAC. A digitally accessible record will show the digitized image of the record at the top of its Record Information Page.

The final blog in this series will provide detailed strategies to navigate the records.

Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour is an archivist in the Government Archives Division of the Government Record Branch at Library and Archives Canada.