By Rebecca Murray

When I was a relatively new acquisition at LAC, a mainstay of archival humour used to refer to new employees, I worked on a question from a researcher who was looking for the given names of a captain who served in the Canadian militia in the 1890s. Full of optimism and energy, I set off in search of this elusive captain.

The researcher knew that, during this time, Evans was stationed in Manitoba, where he was also involved with amateur hockey. After unsuccessful keyword searches in our catalogue, I decided to switch strategies and “follow the money.” Not just an oft-quoted phrase, using financial documents or reports such as pay or purchase records is one of many search strategies you might use to find mentions of otherwise elusive individuals or projects. During this period in Canadian history, the militia was significant, but it was still relatively small in comparison with today’s military. Considering this and knowing about the reporting detail available in the annual reports of the Auditor General and departments from this period, I thought I might be able to find some mention of this Captain Evans.

I scoured reports from the early 1890s and was soon successful. I found a reference to a “Lieutenant T. D. B. Evans” attached to the Mounted Infantry School at Winnipeg, Manitoba (Military District 10) in 1891–1892 in the Auditor General’s annual report (c. 1893).

Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada: volume 1, third session of the seventh Parliament, session 1893, page 1-C-48 [Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1893] (OCLC 858498599)

Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada: volume 1, fourth session of the seventh Parliament, session 1894 [Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1894]; page 1-47 (OCLC 858498599)

Why is this part so important? It gives us a few more keywords to use as we explore the archival database. Here’s the search interface screen showing my search terms and some preliminary results. It’s just one of many variations on the searches I performed. For example, I left out any mention of rank, as I know from the secondary research above that, during this period, Evans was promoted from Lieutenant to Captain. I didn’t want to exclude any potentially relevant results by requesting that “Capt” or “Captain” be part of the results.

The author’s search in Collections and Fonds (Collection Search)

These results also help to answer one of the researcher’s questions: What were the captain’s given names? The first given name (Thomas) is shown in the title of the second search result—a Privy Council Office record related to his promotion from Captain to Major circa 1895.

Although thrilled with these findings, I soon realized that none of this helped me make the link with amateur hockey. So I turned yet again to published sources, this time relying on the database of historical issues of The Globe and Mail, where I found a front page article about Evans’s death that confirms not only all three of his given names—Thomas, Dixon and Byron—but also his presidency of the Manitoba Hockey Association.

DEATH OF COL. T.D.B. EVANS: SUCCUMBED TO SUNSTROKE AFTER SHORT ILLNESS, Commanded Canadian Mounted Rifles in South African War and Was Decorated for His Services—Commanded Winnipeg District, The Globe (1844–1936), Toronto, Ontario, August 24, 1908: 1 (OCLC 1775438)

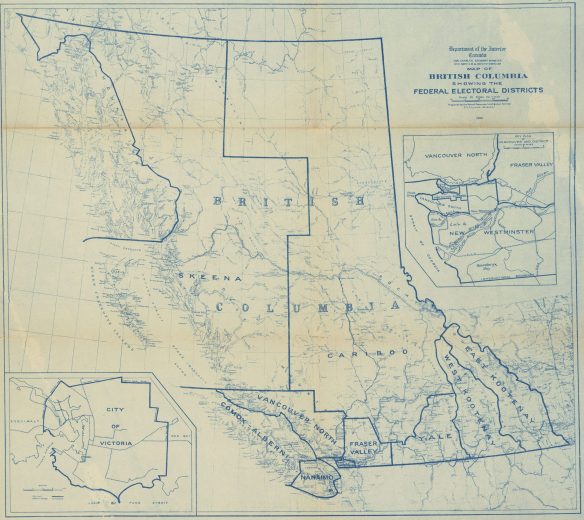

These details allowed me to identify further relevant primary and secondary sources, including orders-in-council held at LAC that track changes throughout Colonel Evans’ military career and photographs from his time in Manitoba.

Lunch ’93. Left to right: H.J. Woodside, Captain T.D.B. Evans, Hosmer, Thibodeau, Elphinstone, 1893. Accession 1967-025, item 167. Credit: Henry Joseph Woodside/Library and Archives Canada/PA-016013

This is the query that really drove home for me the importance of combining archival and published sources held at LAC and of relying on trusted external secondary sources to conduct my work thoroughly and diligently. In hindsight, I can think of many other sources on which I could have drawn, such as census documents (which likely would have included an overwhelming number of individuals named “Evans”), the Canada Gazette, and militia lists. I was lucky in this case to find what I was looking for with relative ease—or so it often seems when recounting one’s search after the fact.

Rebecca Murray is a Senior Reference Archivist in the Reference Services Division at Library and Archives Canada.