By Lucie Paquet

In August 1914, countries in Europe started a war that was expected to be over quickly. Like many Western countries, Canada mobilized and sent troops to fight on the Allied side during the First World War. The French army, largely deprived of heavy industry and mining resources, soon ran out of military materiel, which led to a marked increase in demand for all kinds of products. So from 1914 to 1918, Canada took action to address this situation by requisitioning nearly 540 industrial facilities across the country, from Halifax to Vancouver. Steel factories deemed essential by the government were converted to manufacture war materiel. To support the army, their activities were closely supervised by the Imperial Munitions Board, which appointed and sent more than 2,300 government inspectors to factories to supervise, test and evaluate the production of military goods. It was under these circumstances that The Steel Company of Canada (now Stelco) converted a large part of its operations to produce materiel for war.

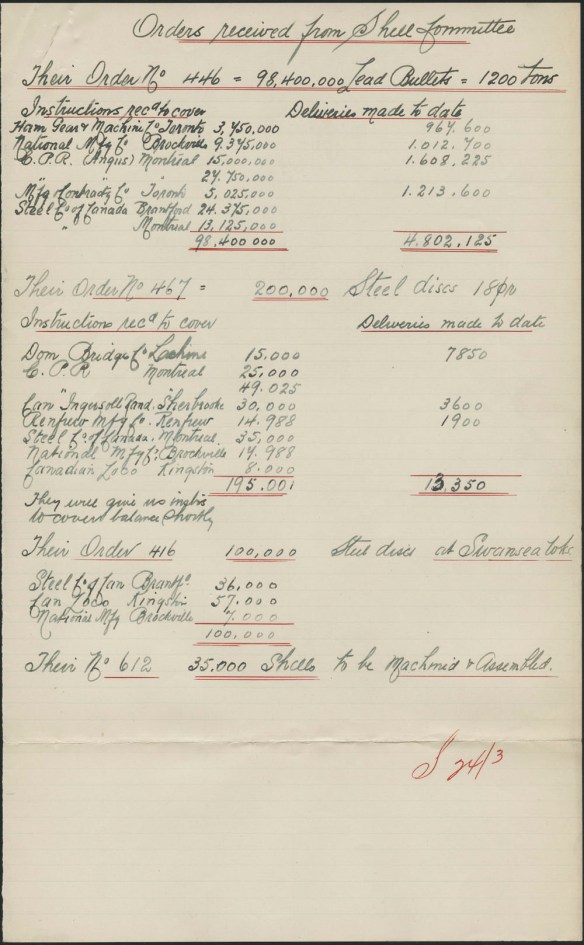

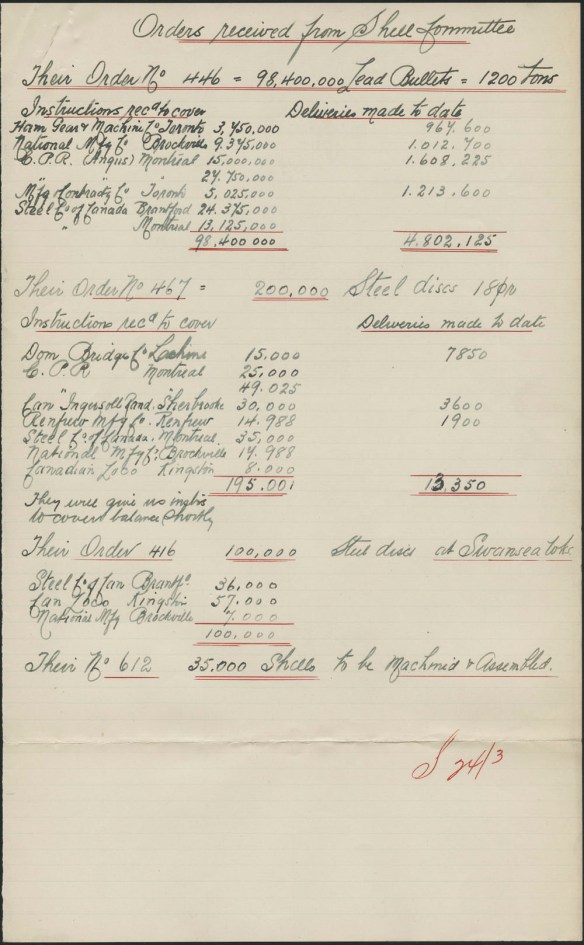

Handwritten list of orders sent by the Imperial Munitions Board detailing the number of shells produced by various industrial facilities in Canada. (e011198346)

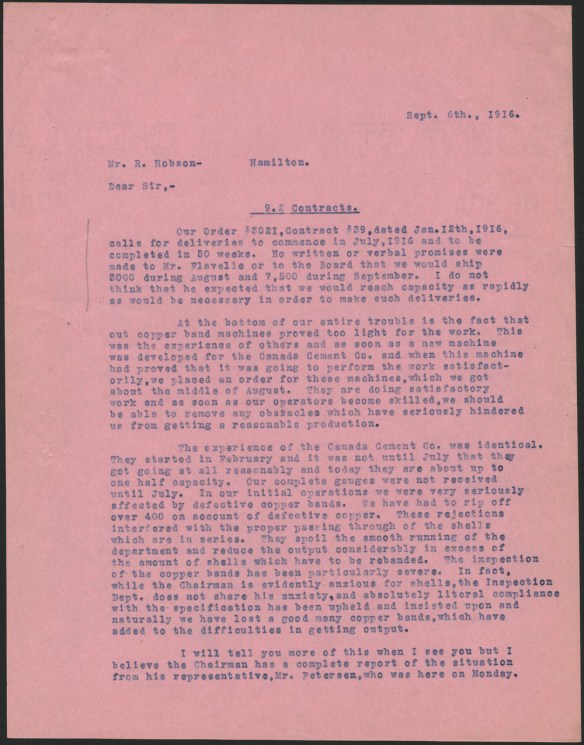

However, this change led to problems. Since the factories were not prepared to manufacture weapons quickly and to ensure consistent high quality, orders were delivered late and, very often, the equipment was defective. Stelco faced this reality and experienced these difficulties.

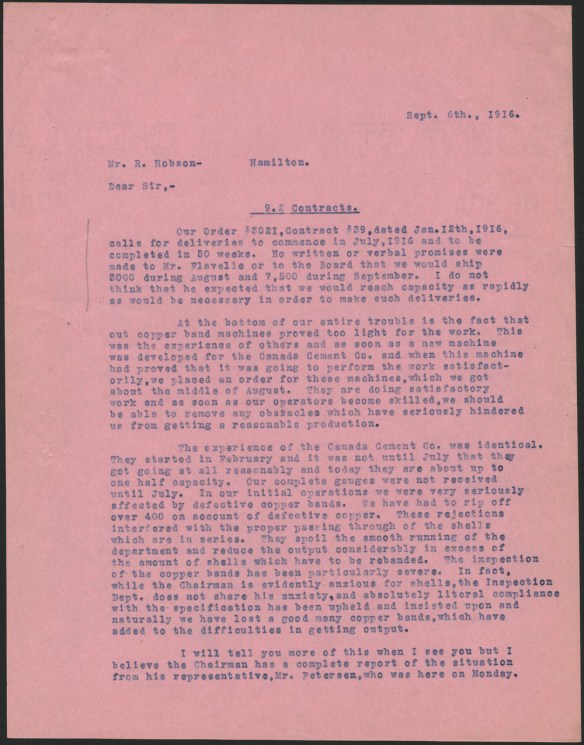

Letter written in September 1916 by Montréal plant manager Ross H. McMaster to Stelco president Robert Hobson describing problems in producing and delivering shells. (e011198359-001)

Stelco’s biggest challenge involved the supply of raw materials. First, these had to be found and extracted; then the raw ore had to be transported from the mines to the plants; the necessary machinery and equipment had to be acquired and the new blast furnaces put into operation; and, finally, workers had to be trained for each stage of the manufacturing process. With its newly electric-powered mill for making steel bars, Stelco was able to start production quickly. It hired women to replace the hundred workers sent to the front, and it bought mining properties in Pennsylvania and Minnesota to supply coal and iron to its factories. Stelco also renovated and modernized its plants.

Statement prepared by Stelco outlining capital expenditures for the construction of new plants and the acquisition of additional equipment (e011198354)

Transportation systems were built to carry raw metals to Stelco’s processing plants in Montréal, Brantford, Gananoque and Hamilton. At the time, most major Canadian cities were linked by the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific railway lines, to transport soldiers and military goods.

Fall 1916 was a turning point in the steel industry, after two years of experimentation and production. As war continued to rage in Europe, metallurgists and industrialists decided to hold strategic meetings. The first meeting of the Metallurgical Association was held in Montréal on October 25, 1916, to discuss scientific advances in manufacturing military equipment. On that occasion, Stelco held an exhibition to showcase its products.

Photos in the Canadian Mining Institute Bulletin showing shells produced by Stelco. (e011198345)

In 1917, Stelco built two new plants in Hamilton. In addition to artillery pieces, steel panels were also manufactured for the construction of ships, rail cars, vehicles and aircraft parts.

As the war intensified, the demand for munitions increased dramatically. Production levels rose, prompting a reorganization of the world of work. To speed up production, workers were now paid wages based on the time allocated to manufacture each part. Bonuses were also awarded to the fastest workers.

Table showing the average number of minutes that workers spent on each step in manufacturing a 9.2-inch shell part, as well as the estimated number of minutes normally required to complete each task. (e011198358)

View of the interior of a munitions and barbed-wire factory in 1916. (e011198375)

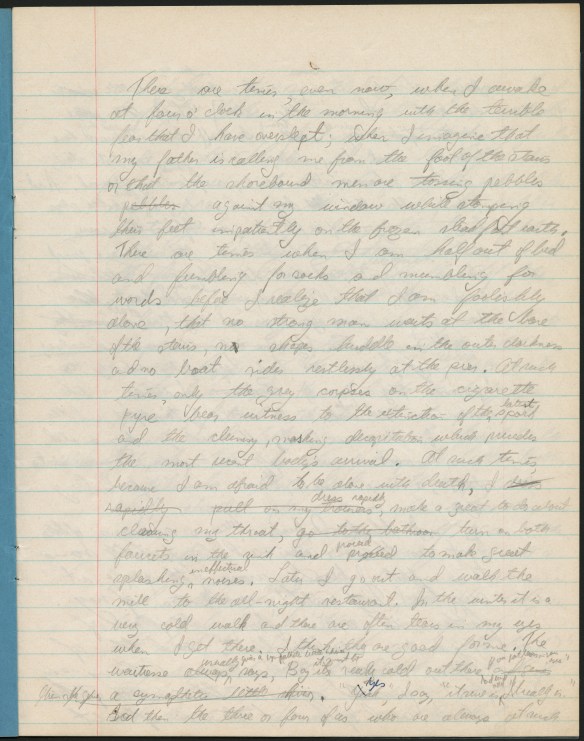

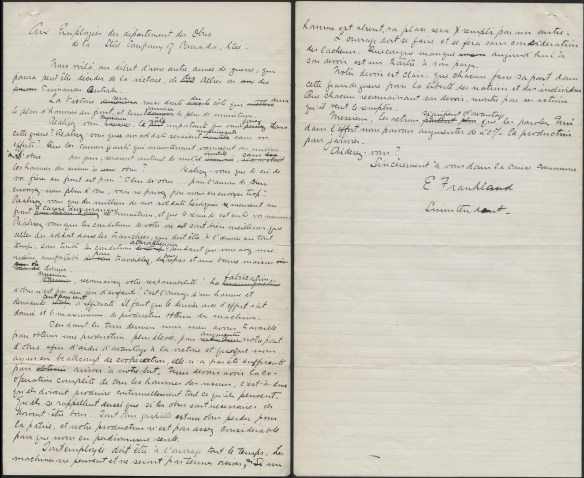

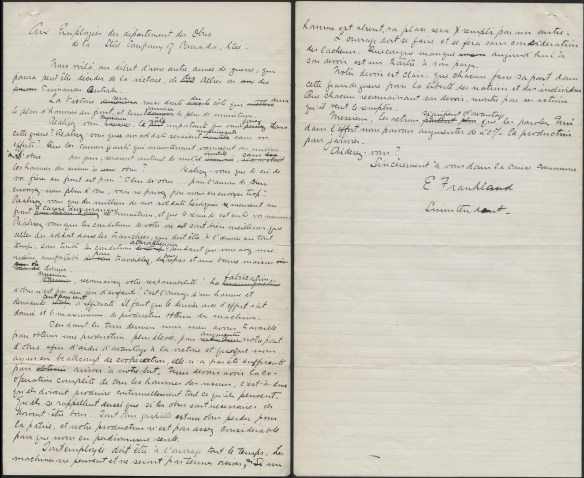

The war effort created a strong sense of brotherhood and patriotism, and workers put their demands on hold. A message from the superintendent of the shell department, delivered on January 4, 1917, clearly shows the pressure in the factories and the crucial role of the workers.

Handwritten letter written by superintendent E. Frankland to employees of Stelco’s shell department. (e011198367; a French version of this letter is also available: e011198368)

More than a hundred workers from the steel mills would fight in the trenches; most of them were sent to France. This list, dated November 16, 1918, shows the name and rank of each worker who went to fight, the name of his battalion or regiment, and his last known home base.

List of Stelco workers who went to fight in the First World War (1914–1918). (e011198365)

Fundraising campaigns were organized during the war to help soldiers and their families. Workers contributed a portion of their wages to the Canadian Patriotic Fund.

Cover page and pages 23 and 24 of a record of contributions to the Canadian Patriotic Fund. (e0111983867 and e011198385)

The work of factory workers was very demanding. Although the tasks required a high degree of precision, they were repetitive and had to be performed swiftly on the production line.

Left, Stelco workers on a production line for 9.2-inch shells. Right, an Imperial Munitions Board form for progress achieved by a production line in a given week. (e011198374 and e011198362)

The products were heavy and dangerous to handle. The workers melted the steel in the blast furnaces and then poured it into rectangular moulds. With tongs, they removed the glowing hot steel ingots and placed them on wagons. The ingots were then transported to the forge, where they were rolled into round bars according to the dimensions required to form the various shell tubes.

Reproduction of a photograph of a worker using long tongs to remove a glowing hot 80-pound steel ingot from a 500-tonne press. (e01118391)

Stelco workers pose proudly beside hundreds of shell cylinders made from molten steel. (e01118373)

A large quantity of steel bars was produced to manufacture 9.2-inch, 8-inch, 6.45-inch and 4.5-inch shells.

View of the inside of Stelco’s shell factory on Notre-Dame Street, Montréal, May 12, 1916. (e01118377)

In 1915, Stelco’s plants in Brantford, Ontario, and on Notre-Dame Street in Montréal forged some 119,000 shells. The combined production of the two plants increased to 537,555 shells in 1917, then reached 1,312,616 shells in 1918. Under great pressure, Canadian factories continued to process millions of tonnes of steel into military materiel until the Armistice ending the First World War was signed in November 1918.

Lucie Paquet is a senior archivist in the Science, Governance and Political Division at Library and Archives Canada