By J. Andrew Ross

Last year, the National Hockey League (NHL) celebrated the 125th anniversary of the Stanley Cup. The celebration year was no doubt chosen because 2017 was also the NHL’s centennial year. However, even though 125 years earlier, on March 18, 1892, it had been announced that Governor General Frederick Arthur Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley, wished to donate a challenge cup for the hockey championship of the Dominion of Canada, that cup only arrived in Canada the following year. Further complicating matters, the team that was to receive the Stanley Cup actually refused it, and was only persuaded to take possession of the trophy in 1894.

Anniversaries aside, the story of how the Stanley Cup eventually became Canada’s holiest sports icon can be told through the collection of Library and Archives Canada.

By the time his cup arrived in Canada, Stanley had returned to England before the end of his term as governor general, having become the 16th Earl of Derby upon his brother’s death. Stanley appointed Ottawa Evening Journal publisher Philip Dansken (“P.D.”) Ross as one of two trustees of the trophy, and left it to him to fashion the rules of competition.

The entry in Ross’s diary for Sunday, April 23, 1893, notes that he sat down that day to draft the new rules, which were printed in his newspaper on May 1, 1893.

Excerpt from “The Stanley Cup,” Evening Journal (Ottawa), May 1, 1893, page 5 (AMICUS 7655475)

While the bowl had already been engraved as the “Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup,” Ross immediately asserted that it should be known as the Stanley Cup in honour of its donor. He confirmed that it would be presented in the first instance to the reigning champions of the elite hockey league of the era, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC), with the idea that they would then defend it against the champions of the Ontario Hockey Association. Ross arranged for the Stanley Cup to be presented to the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (MAAA) team as the reigning champions of the AHAC, “until the championship of the [AHAC] … be decided next year [i.e., 1894], when the Cup shall go to the winning team.”

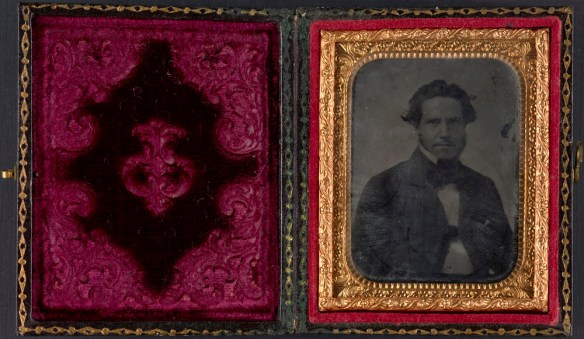

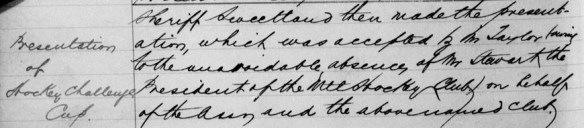

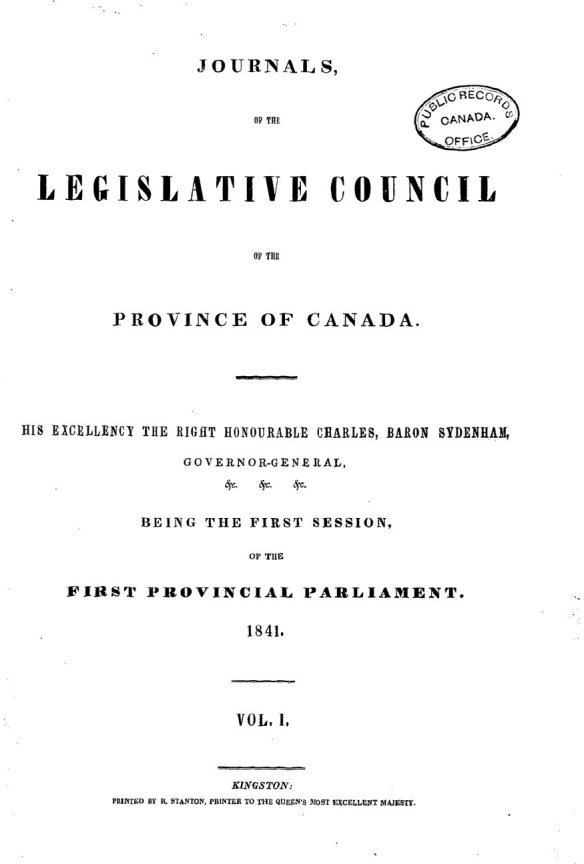

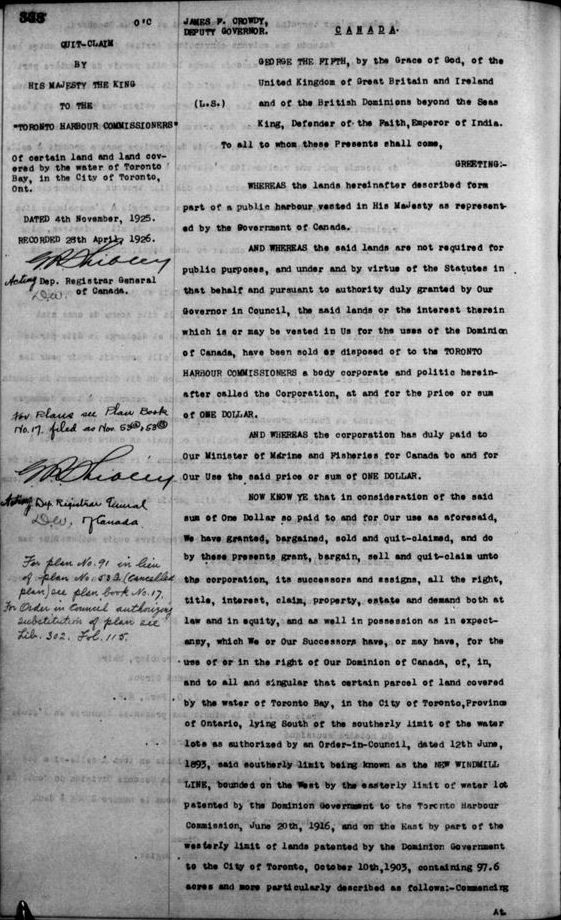

On May 15, 1893, Sheriff John Sweetland of Ottawa, the other Stanley Cup trustee, travelled to Montreal to present the trophy at the MAAA’s annual meeting. When he arrived with the Stanley Cup—at that time just a simple bowl on a wooden base—he learned that the executive officers of the hockey team had declined to attend the ceremony. The minutes of the meeting, which are in the MAAA fonds (and available online), note: “Sheriff Sweetland then made the presentation, which was accepted by Mr. Taylor [the MAAA president] owing to the unavoidable absence of Mr Stewart the President of the Mtl Hockey Club on behalf of the Assn and the abovenamed club.”

Extract from the May 15, 1893, annual meeting, page 315, MAAA Minute-book, MG28 I 351, Library and Archives Canada.

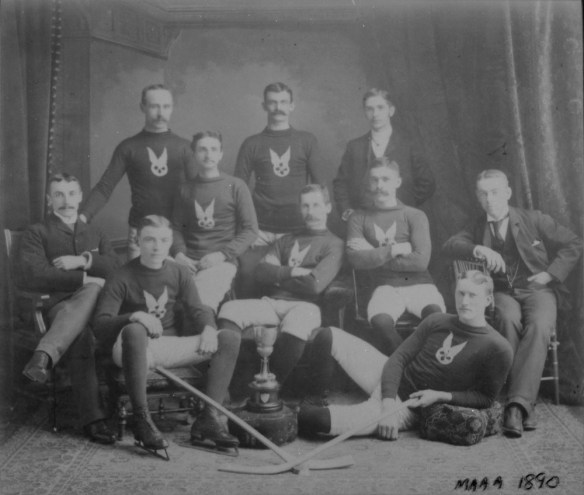

It is not clear whether Sweetland realized that he and the Cup had been snubbed, but the hockey club’s absence had not been “unavoidable.” They had deliberately boycotted the event upon learning that the Cup was to be presented to the MAAA executive and not the team—and that the Cup had been engraved with “Montreal AAA/1893” on a ring around the wooden base of the bowl. The conflict was apparently rooted in the resentment of the hockey club members about being known by the name “MAAA,” rather than the Montreal Hockey Club (Montreal HC). It was a petty point of honour since the hockey club wore the MAAA emblem of the winged wheel on their uniforms, but one that clearly mattered to the proud hockey players.

MAAA 1890 (Montreal Hockey Club) (Hockey Hall of Fame/Library and Archives Canada/PA-050689). Credit: Hockey Hall of Fame.

It was only after almost a year of contentious negotiations—at one point, the MAAA threatened to send the Cup back to the trustees!—that, in March 1894, the Montreal HC finally agreed to take possession of the Stanley Cup. A few weeks later, the club won the AHAC championship yet again, making them the first winners (as opposed to simply the holders) of the Cup. This time, the team took responsibility for the engraving, and pointedly used “Montreal 1894.” With no reference being made to the MAAA, honour was seemingly served.

The next season, the Montreal HC became the first team to successfully defend the trophy in the first Stanley Cup series. Its insistence on getting its own name on the Cup may have been worth the effort, even if its prolonged refusal to accept the trophy risked making the Cup irrelevant. But the Stanley Cup was finally awarded, and the rest is history.

Andrew Ross is an archivist in the Government Archives Division, and the author of Joining the Clubs: The Business of the National Hockey League to 1945.

![A colour photograph of a record label that reads “Improved Berliner Gram-O-Phone Record. Manufactured by [illegible] Montreal, Canada. Patented [illegible] 1897. Ye Banks and Braes. Played by The Kilties Band – Belleville, Ont.”](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/313832901.jpg?w=584)