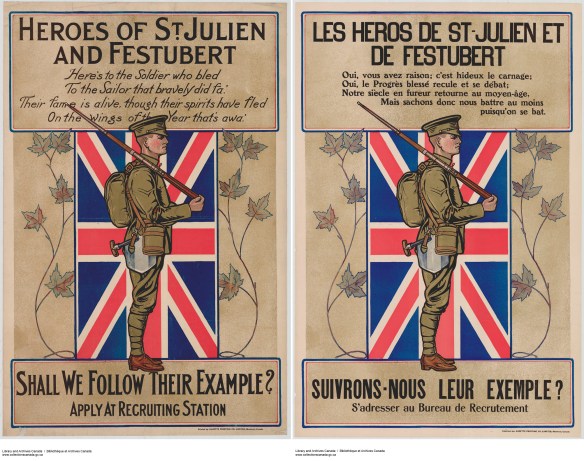

The recruiting posters below are part of a remarkable collection of more than 4,000 posters from many combatant nations, acquired under the guidance of Dominion Archivist Dr. Arthur Doughty as part of a larger effort to document the First World War.

An English and French version of a poster using the same imagery, but with text conveying very different motivations. (MIKAN 3667198 and MIKAN 3635530)

As the deadly stalemate on the Western Front continued through 1915, warring nations were forced to organize recruitment drives to raise new divisions of men for the fighting. The two battles referenced in the poster were certainly not great victories for the Canadian Expeditionary Force, which had only recently commenced military operations. The desperate defence at St. Julien, an action during the Second Battle of Ypres, along with the inconclusive May 1915 Battle of Festubert, were all that authorities had to draw upon to raise fresh troops for service overseas.

The sentimental verse and patriotic imagery was conventional for this type of poster. It would appeal to Canadians with strong ties to Britain, but would offer little encouragement to French Canadians, First Nations’ communities, or to other groups to sign up. One interesting element is that the text is not a simple translation: in English the theme is heroic sacrifice, whereas in French it is about ending the carnage and restoring “progress.”

These posters offer a realistic depiction of a soldier early on in the war. This lance-corporal is armed with the Ross rifle, whose serious defects have featured in Canadian histories of the First World War. He is wearing short ankle boots and puttees (long lengths of cloth wrapped around his calves), which were cheaper to manufacture than knee-length boots but offered less protection from cold or wet. Steel helmets had not yet been developed, leaving his head and upper body vulnerable to any flying debris or shrapnel.

He is also burdened by the MacAdam shield-shovel (hanging at his hip). This invention was the result of a collaboration between Minister of Militia Sir Sam Hughes, and his secretary, Ena MacAdam. It attempted to combine a personal shield with a shovel. The shovel blade had a sight hole in it that was supposed to allow a soldier lying on the ground to aim and fire his rifle through the hole while shielded behind its protection. However, the shovel was too heavy and dirt would pour through the hole. Also, the shield was too thin to stop German bullets! Thankfully, this failed multi-tool quietly disappeared from the standard equipment issued before the First Division crossed from England to France. This poster is an important artifact of its time. It shows that in 1915, Canadians soldiers fighting overseas still had a very long road ahead of them.

Sam Hughes holding the McAdam shield-shovel (MIKAN 3195178)