This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

This is Part 2 of the blog series Puzzling through 1931 Census sub-districts. If not done already, you may want to read Part 1, as it provides tools to help identify the census district that would have included your place of interest in 1931.

As a reminder from Part 1, to find the census returns for a place of interest, we generally need to narrow down, in order, the:

- province or territory;

- census district or federal electoral district; and

- census sub-district

that would have included the place of interest in 1931.

In this blog post, we go over the last step.

STEP 3. Determining the census sub-district

Each 1931 Census district was divided into multiple sub-districts – anywhere from three to 148 – for the purpose of enumeration. The majority of census districts were divided into at least 50 sub-districts.

The hitch is that no maps of 1931 Census sub-district boundaries are known to still exist. Figuring out in which census sub-district one’s place of interest was enumerated requires using one of the following tools:

- Street indexes (for 11 major cities)

- Finding aid for “Indian Reserves” (First Nations)

- Written descriptions of sub-district boundaries.

If your place of interest was in neither a major city nor a First Nations Reserve in 1931, skip directly to the last tool, the written descriptions of sub-district boundaries.

Tool 1: Street indexes

Indexes are available for Halifax (N.S.), Saint John (N.B.), Quebec (Que.), Montréal (Que.), Toronto (Ont.), Hamilton (Ont.), London (Ont.), Winnipeg (Man.), Edmonton (Alta.), Calgary (Alta.) and Vancouver (B.C.). Street indexes list street names and indicate in which census district and sub-district(s) those streets were enumerated.

The indexes for Hamilton and Calgary are specific to the 1931 Census. The indexes for the remaining cities cover multiple census years. In those indexes, for the purposes of locating district numbers for the 1931 Census, consider only entries beginning with “31.” The numbers that follow are the district and sub-district numbers, respectively, for 1931. So, for instance, if we are looking for a place of interest on Montréal’s Chemin de la Côte-des-Neiges in the census district of Mont-Royal (Census District no. 84), we find:

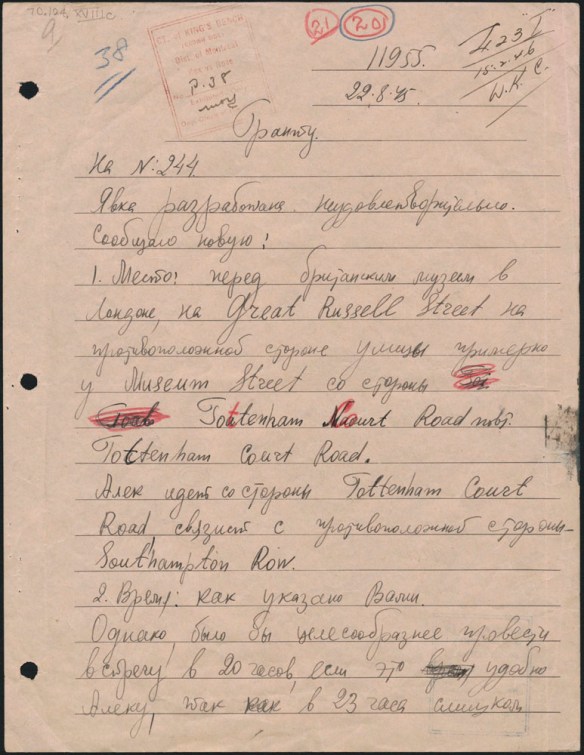

Excerpt from the Montréal Street Index (Finding Aid 31–80)

The numbers in the first line depicted above – “31–84–39, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45” – indicate that, in 1931, Chemin de la Côte-des-Neiges was enumerated in Census District no. 84, in census sub-districts 39 through 41 and 43 through 45.

Note: the street names featured in the indexes are historical; in other words, they are as written by the enumerator at the time, generally speaking.

Beware: the same street may have had its name written in multiple ways and thus appear in separate parts of the alphabetically ordered street index. In the case of Montréal’s Chemin de la Côte–des–Neiges, entries are spread across three separate areas of the Montréal index, with the street name written as “Côte-des-Neiges,” “Côte des Neiges” and “Cote des Neiges.”

Tool 2: Finding aid for “Indian Reserves” (First Nations)

A listing of reserves by 1931 Census district and sub-district is available. This unverified finding aid could be useful if your place of interest was (in) a First Nations Reserve in 1931. We are currently working to adapt this pre-existing finding aid to include respectful terminology.

Tool 3: Written descriptions of sub-district boundaries

Written descriptions of sub-district boundaries were compiled by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics. These descriptions have been transcribed into finding aids for each province or territory: P.E.I., N.S., N.B., Que., Ont., Man., Sask., Alta., B.C., Y.T., N.T.

Note: the transcription of sub-district descriptions for select major cities may be forthcoming.

You may choose to begin with a keyword search related to your place of interest in the finding aid for a province or territory. For example, searching the Manitoba sub-district description finding aid for “Birtle” yields three results within the census district “Marquette”: sub-district 25 for “Birtle (Town)”; sub-district 24 for “Township 17 in range 26 west of the principal meridian exclusive of town of Birtle”; and sub-district 63 for the residential school of the same name. Alternatively, you may choose to navigate to a particular census district (like “Marquette”), then browse all sub-district descriptions within that census district.

Excerpt from the Finding Aid for the 1931 Census Returns for Manitoba (Finding Aid 31–80)

The characterization of census sub-districts varies tremendously. The descriptions may refer to townships, municipalities, city wards, polling divisions, reserves, parishes, meridians, ranges, lots, roads, islands, rivers, etc. Making sense of the descriptions may require consulting local maps from the era or learning about the local, provincial or other federal geographies leveraged for the purposes of the 1931 Census (e.g., municipal boundaries may have been established in contemporary provincial law).

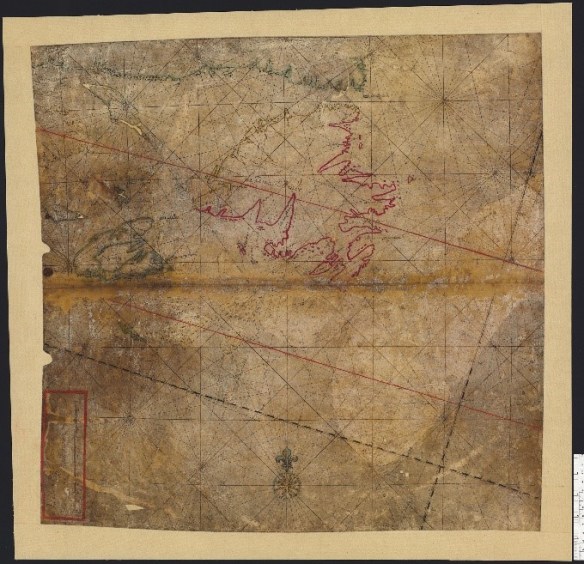

Sometimes the sub-district descriptions do not themselves allow us to narrow things down to a single sub-district. To illustrate what we mean by that, we can look at sub-district descriptions for the census district of Mont-Royal.

The Dominion Bureau of Statistics’ working description of sub-districts in District 84, Mont-Royal (from material accompanying the transfer of the 1931 Census returns to Library and Archives Canada). Library and Archives Canada/Statistics Canada fonds/District 84, Mont-Royal, Quebec, 1931

The sub-district descriptions for Mont-Royal create a situation in which it is challenging to identify a single sub-district of relevance. If you face this situation, you then have two options:

- flip through the census returns for all relevant sub-districts; or

- narrow things down using other working tools, such as city directories, which might list wards, or using additional tools such as a Street Index, which is likely the best approach in the case of Montréal.

Sometimes additional sub-district descriptions feature on the title card preceding the sub-district’s census returns. Scans of the original Dominion Bureau of Statistics’ working descriptions of sub-districts are available online and, though cumbersome, may be used for troubleshooting purposes. To view these scans, go to the archival description for the 1931 Census returns in Collections Search, toggle open the details, then toggle open the finding aid section and scroll down.

Additional resources

- To learn about the system of townships, ranges and meridians used in the three prairie provinces and the railway belt of British Columbia, consult the section titled Western Canada Land System Description on the homepage for our Land Grants of Western Canada database.

- The blog post “Finding Royalton: Searching the 1921 Census” describes how a staff member locates small rural hamlets or unincorporated villages. It offers insights and ideas about how to overcome stalemates.

- If you had already found your place of interest among the census returns from the 1921 Census of Canada or 1926 Census of Prairie Provinces, consider viewing the sub-district description in Census Search for that earlier census year. It might assist you in navigating the sub-district descriptions for the 1931 Census.

Again, wishing us all the best in our searches for people and places of the past.

As always, don’t forget that we can help: reach out to our genealogy team by using our Ask genealogy a question online form.