By Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour

Cradleboards are still an integral part of the cultural practices of First Nations peoples. I experienced using a cradleboard for my family when we received one from my mother-in-law. It was not new, the paint was flaking off and its footrest was wobbly. An antique restorer stabilized the paint and repaired the footrest. I selected a floral printed fabric to make a pad and embroidered a long sash of denim with multiple colours. I bundled my infant daughter in a thin flannel blanket, placed her on the cradleboard and wrapped the sash snugly around her. She was content when on the cradleboard and would usually fall asleep within minutes. I used it to bring her to local community events. Unfortunately, she outgrew it in about a month.

The cradleboard now decorates my home and is a reminder of those first few months of her life—it brings back cherished memories. Only later did I become aware of its cultural and historical significance while reading a book on First Nations cultural materials. The features of our cradleboard matched one that was over a hundred years old. Early First Nations cradleboards are in museums or private collections, as anthropologists and antique collectors visited communities and approached families directly to purchase and collect them.

Caughnawaga [Kahnawake] reserve near Montréal [left to right: Kahentinetha Horn (née Delisle), Joseph Assenaienton Horn, Peter Ronaiakarakete Horn (Senior) holding Peter Horn (Junior), Theresa Deer (née Horn), Lilie Meloche (née Horn), unknown, Andrew Horn, unknown], ca. 1910 (e010859891)

Two young girls standing on a wooden porch beside a boy in a cradleboard, Temagami First Nation, probably Lake Temagami, Ontario, unknown date (e011156793)

The construction of a cradleboard starts with a flat plank of wood to which functional components are added. The handle or canopy is at the top end and provides protection for the head. This part may be a bar of curved wood or a canopy of arched bark. A flat piece of wood or bark rail is attached close to the bottom of the board as a footrest and keeps the infant in place when the board is placed in an upright position. Materials that are used for the cradleboard may include wood, leather, bark, cord, plant fibres, woven fabrics or a combination of these. Cradleboards can be stylized by carving, shaping, painting or adding decoration to the different components. Since a newborn grows quickly, a second, larger board may be used to accommodate a growth spurt. Boards may be shared between families, with a new mother borrowing one when needed. Cradleboards can be commissioned ahead of the arrival of an infant and range from a simple utilitarian style to more artistic creations.

Atikamekw woman, infant on a cradleboard and young girl in a canoe, Sanmaur, Quebec, ca. 1928 (a044224)

A cradleboard enables a mother to return to her daily activities more easily after birth, while keeping her newborn close by her. The infant can be carried safely, while being comforted by the stimulation of being swaddled. Swaddling is done by bundling the newborn and securing its arms in a thin blanket with light pressure. This is thought to be good for the infant’s posture, as the back is flat on the board and the spine can be kept straight. When the cradleboard is placed horizontally, a cross bar attached under the board on the top end raises the head slightly higher than the bottom end. Using gravity, the infant’s blood circulation is enhanced. Of course, not all of the infant’s early life is spent on the cradleboard, as it is used as occasions warrant.

First Nations family, Ishkaugua portage, [Newton Island, Ontario], 1905 (a059502)

Smaller versions of cradleboards are made for the children. These provide the opportunity for young girls to practice their nurturing skills while at play and prepares them for motherhood or caregiving. A cloth or corn-husk doll or a bundle of sage or other dried plant material is usually placed on the board

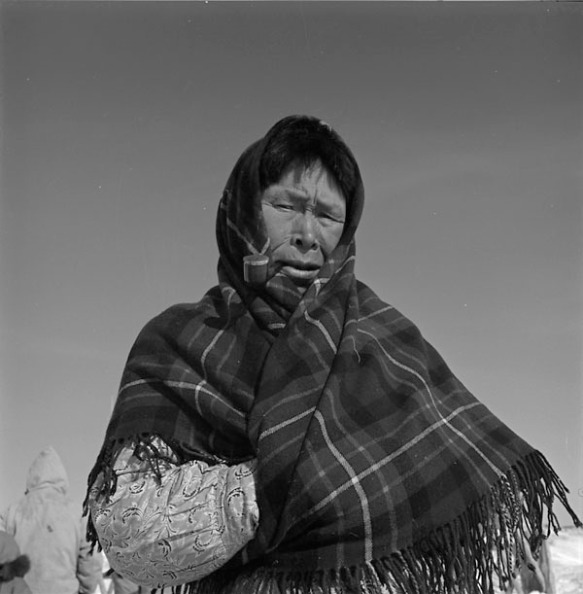

Cree women and children at Little Grand Rapids, Manitoba, 1925 (a019995)

Eastern area

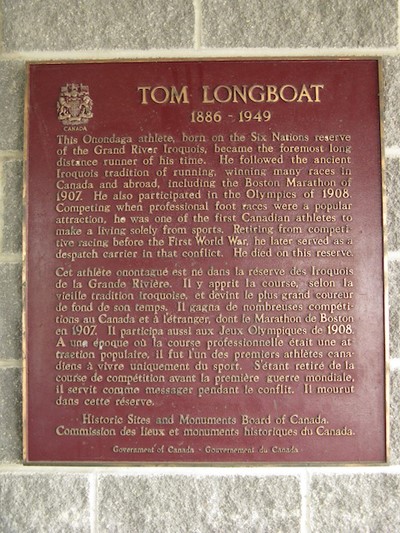

Haudenosaunee (Six Nations/Iroquois) and Algonquin-style cradleboards start with a flat plank of wood. On the backs of older Haudenosaunee boards, there are usually low-relief carved images of animals, flowers and leaves painted in basic colours of red, black, green, yellow and blue. There may be additional carving on the top end of the board, handle, footboard and wood bar. In rare examples, silver or metal inlays have been inserted on the wood bar.

Kenneth Atsenienton (“the fire still burns”) Deer and grandson Shakowennenhawi (“he is carrying the words”) Deer at the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Kahnawake, Quebec, May 1993 (e011207022)

Some of the wooden structural elements were attached with wood pegs. Handles were reinforced with leather strips, gut or cord. The curves on the wood handles were hardwood that had been steamed and bent. Haudenosaunee wood handles were straight across, while the Algonquin boards had a bowed wood handle. A cover can be draped over the handle to provide a quiet space or shield the infant from the elements. Objects might be hung from the handle for the child to look at, such as beaded strings, charms or possibly a baby rattle. Some Algonquin cradleboards had a one-piece rail attached to the board, which would go up each side, curving at the bottom and serving as a footrest.

A cradleboard could be carried on a person’s back by attaching straps or a tumpline to the cradleboard; these then went around the chest or forehead and left the hands free.

This watercolour painting shows a woman carrying a baby in a cradleboard, ca. 1825–1826 (e008299398)

Western area

First Nations in the Plains region would cover the leather or fabric used for the cradleboard with their traditional beadwork styles. The infant was placed in an enveloping enclosure attached to the cradleboard.

Northwest Coast First Nations had more than one type of cradleboard, as well as a dugout-trough cradle. Cradleboards were made of woven plant fibres, cedar boards and hollowed-out logs.

The tradition of making new cradleboards is carried on today by First Nations carvers and craftspeople. In celebration of the birth of new generations, they may incorporate past knowledge in new designs including personalized elements and stylistic representations of present culture.

Visit the Flickr album for more images of cradleboards.

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.

Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour is a project archivist in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division of the Public Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg?w=584)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=519&h=142)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg?w=519&h=142)