Version française

By Mariam Lafrenie

It goes without saying that the Right Honourable Lester B. Pearson achieved much in his life. Whether you look at his success politically, academically or even athletically—Pearson always excelled. Although Pearson served as Canada’s prime minister from 1963 to 1968, his legacy and indeed his influence began long before his prime ministership: as chairman of the NATO council (1951), as President of the United Nations General Assembly (1952), and as a Nobel Peace prizewinner (1957).

Nevertheless, Pearson’s five-year legacy is very impressive: a new flag, the Canada Pension Plan, universal medicare, a new immigration act, a fund for rural economic development, and the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism which led to the foundation of a bilingual civil service.

Lester B. Pearson and his wife, Maryon at the Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony, Oslo, Norway, December 1957. Photograph by Duncan Cameron. (c094168)

Lester B. Pearson, at the United Nations Conference on International Organization, San Francisco, Calif., USA, 1945. (c018532)

Rising quickly through the ranks and moving from one portfolio to another, Pearson proved himself a worthy and talented diplomat. After a 20-year career in External Affairs, his success did not end there, but followed him throughout the next decade as leader of the Liberal Party (1958-1968). Without a doubt, some of his most exciting—if not his most significant achievements—came during his time as Prime Minister.

A flag for Canada

The quest for a Canadian flag—one that represented everything that Canada had become in the last century and all that Pearson hoped it could become—was fraught with bitter debate and controversy. Indeed, as many may recall, “The Great Flag Debate” raged for the better part of 1964 and saw the submission of approximately 3,000 designs by Canadians young and old.

“Under this flag may our youth find new inspiration for loyalty to Canada; for a patriotism based on no mean or narrow purpose, but on the deep and equal pride that all Canadians will feel for every part of this good land.” – Address on the inauguration of the National Flag of Canada, February 15, 1965

These words, spoken by Lester B. Pearson during the inaugural ceremony of the Red Maple Leaf flag on February 15, 1965 at Parliament Hill, highlight precisely what he aspired to achieve—a uniquely Canadian identity. Few prime ministers can attest to leaving a legacy so great as to have forged an entirely new cultural symbol for their country.

Lester B. Pearson’s press conference regarding the new flag, December 1964. Photograph by Duncan Cameron. (a136153)

A year of celebration

Not only was Pearson responsible for championing a new Canadian flag, but he was also lucky enough to remain in office during Canada’s centennial year. In his Dominion Day speech on July 1, 1967, Pearson called on Canadians to celebrate their past and their achievements, but also encouraged them to think of the future and of the legacy that they could leave for the next generation of Canadians. Much like this year, when we celebrated Canada’s 150th anniversary of Confederation and were encouraged to think of our future as a nation, 1967 was also a year filled with celebrations.

The aim of the centennial celebrations were twofold: to create memorable events and activities for all Canadians and to create a tangible legacy that current and future generations could enjoy. In fact, both the provincial and federal governments encouraged Canadians to celebrate by creating their own centennial projects—films, parades and festivals, tattoos, recreation centres, stadiums, etc.—and agreed to match their spending. One of the most memorable celebrations was that of the 1967 International and Universal Exposition or Expo 67, as it was nicknamed. Open from April 27 to October 29, Expo 67 is considered one of the most successful World’s Fairs and one of Canada’s landmark moments.

Expo 67’s opening day with its General Commissioner Pierre Dupuy, Governor General of Canada Roland Michener, Prime Minister of Canada Lester Bowles Pearson, Premier of Québec Daniel Johnson and Mayor of Montréal Jean Drapeau. (e000990918)

For many Canadians, 1967 characterized the peak of nostalgia and indeed a year filled with optimism. With this optimism and increased governmental spending, Pearson’s popularity boomed and further solidified his accomplishments as prime minister and widespread support for the Liberal Party amongst Canadians.

Conclusion

Forty-five years ago, on December 27, 1972, after a long and successful political career, Lester B. Pearson passed away. His passing struck a chord with many Canadians as more than 1,200 people attended his funeral service to pay their last respects. Pearson’s legacy and indeed his name are still present today in the numerous awards and buildings named in his honour. Paving the way for what many Canadians and the international community alike have come to love about Canada, Pearson can be said to have shaped and indeed laid the foundation for the Canada we know today.

Prime Minister of Canada Lester Bowles Pearson in front of the Katimavik at Expo 67. (e000996593)

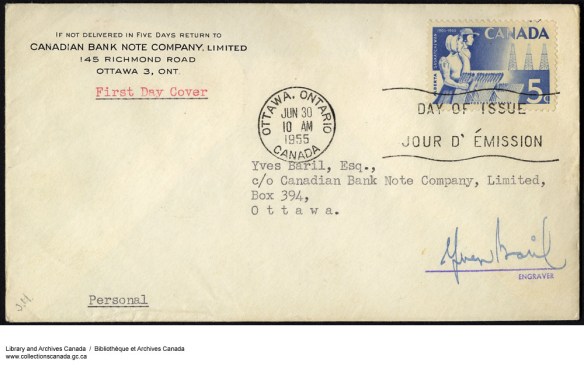

The Lester B. Pearson fonds preserved by Library and Archives Canada consists of 435.71 meters of textual records, over 3,500 photographs, 315 audio recordings on various formats, 3 films totalling 47 minutes, 54 items of documentary art, and 98 medals.

Related links

Mariam Lafrenie is an undergraduate student research fellow from Queen’s University who worked in the Private Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada during the summer of 2017.

Crowdsourcing has arrived at Library and Archives Canada (LAC). You can now transcribe, add keywords and image tags, translate content from an image or document and add descriptions to digitized images using Co-Lab and the new Collection SearchBETA.

Crowdsourcing has arrived at Library and Archives Canada (LAC). You can now transcribe, add keywords and image tags, translate content from an image or document and add descriptions to digitized images using Co-Lab and the new Collection SearchBETA. Contribute using Collection SearchBETA

Contribute using Collection SearchBETA