By Jennifer Anderson

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) is about more than just “stuff”; it is also the home of leading experts in Canadian history and culture. While LAC archivist Jennifer Anderson was at the Canadian Museum of History (CMH) on an Interchange Canada agreement, she co-curated the popular exhibition, “Hockey.” During the exhibition research, she consulted LAC staff and experts across the country. LAC also loaned 30 artifacts to the museum for this exhibition, and offered digital copies of hockey images from its vaults.

You can see the results that teamwork brings! Having run from March 10 until October 9, 2017 in Gatineau, the exhibition will start up again on November 25, 2017 (the 100th anniversary of the NHL) in Montréal at Pointe-à-Callière, before continuing its cross-country tour.

“Hockey”: the exhibition that started with a book…

…or two…or a few hundred. Biographies, autobiographies, histories—comic books, and novels for young people; we read those, too! And as many newspaper and magazine articles as we could find.

The exhibition team swapped books like fans trade hockey cards!

Books moved us, pushed us, challenged us and at times even frightened us. I cried and laughed over them, took notes and then forgot to because I was too engrossed in the reading. We read about big personalities like Maurice Richard and Pat Burns, about game changers like Sheldon Kennedy and Jordin Tootoo, and about Ken Dryden’s observations of young people and families in the game. We were deeply inspired by Jacques Demers’ work to advance youth literacy initiatives. Borrowing literacy teachers’ best practices, we chose to use fonts of different sizes and based the look of our exhibit on the style of a hockey card. The goal: make reading fun and accessible.

One of the first books I read was Paul Kitchen’s fascinating tale of the early history of the Ottawa Senators, Win, Tie or Wrangle (2008). Kitchen did much of his research from a desk at LAC, and he spun some of his discoveries into an online exhibition, Backcheck. From his book, we were able to identify a little-known shinty medallion depicting a stick-and-ball game, which took place on the grounds of Rideau Hall in 1852. Drawing on Kitchen’s footnotes, I reached out to the Bytown Museum, and was thrilled to learn they would be happy to lend the artifact for the exhibit. The conservators at the CMH buffed it up a bit, and images of this early piece of hockey history were included in the exhibition souvenir catalogue.

Front and back views of the silver New Edinburgh Shintie Club medallion, 1852, Bytown Museum, A203. Canadian Museum of History photos, IMG2016-0253-0001-Dm, IMG2016-0253-0001-Dm.

Paul Kitchen would probably be the first to acknowledge that any research project is a team sport, and our exhibition team reached out to many experts who had earlier worked with Kitchen, or had been inspired by him. Within LAC, Normand Laplante, Andrew Ross, and Dalton Campbell have continued the tradition of sports history, and their archival work led us to explore LAC’s collections for material to place in the exhibit. At the CMH, there are hockey experts galore, but Jenny Ellison is the “captain.” The team brought on Joe Pelletier as a research assistant to scout out images and hidden bits of information, based on the work he had already provided voluntarily. Hockey researchers and curators from across the country sent us artifacts, images and information.

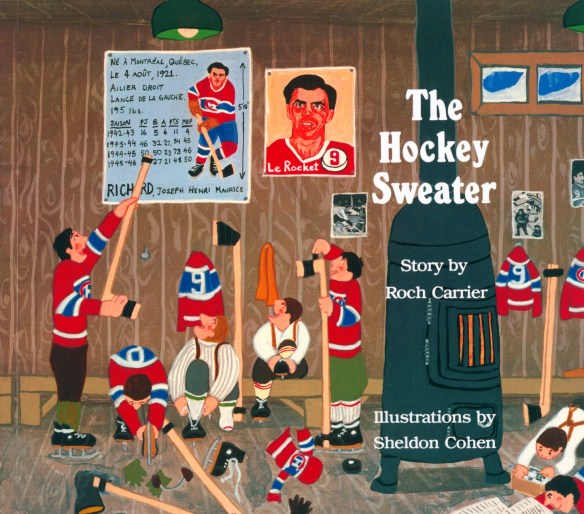

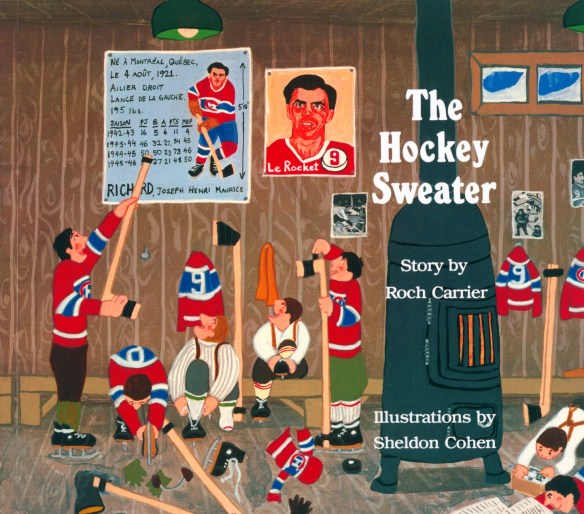

Loaning originals is such an important part of the diffusion of any collection. Thirty individual items were loaned by LAC to the CMH for this exhibition. The LAC Loans and Exhibitions Officer admitted to being particularly touched by the team’s interest in The Hockey Sweater by Roch Carrier (now a popular animated film). As a child, she had received this book from one of her best friends, and only recently located this much-loved book. She has since shared it with her own children, and enjoyed telling them about her own childhood memories of this popular story about hockey.

The Hockey Sweater by Roch Carrier and illustrated by Sheldon Cohen. Used by permission of Tundra Books, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited (AMICUS 4685355)

Carolyn Cook, LAC curator, was pleased to see Bryan Adams’ portrait of Cassie Campbell in the exhibition. This portrait was one of several taken by Adams for Made in Canada, a book of photographs of famous Canadian women sold as a fundraiser for breast cancer research. “Cassie Campbell is an iconic figure in the world of women’s hockey,” said Cook. “Her on-ice accomplishments opened the door to the next generation of girls coming up in the game and, as the first woman to do colour commentary on ‘Hockey Night in Canada,’ she has broken through the glass ceiling. This close-up portrait of her exudes strength, control and determination—qualities that have contributed to Campbell’s success.”

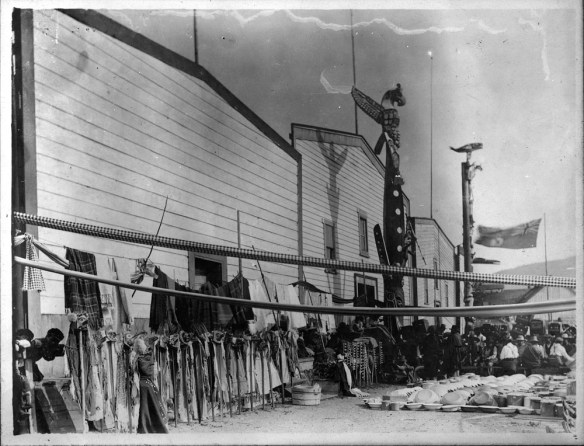

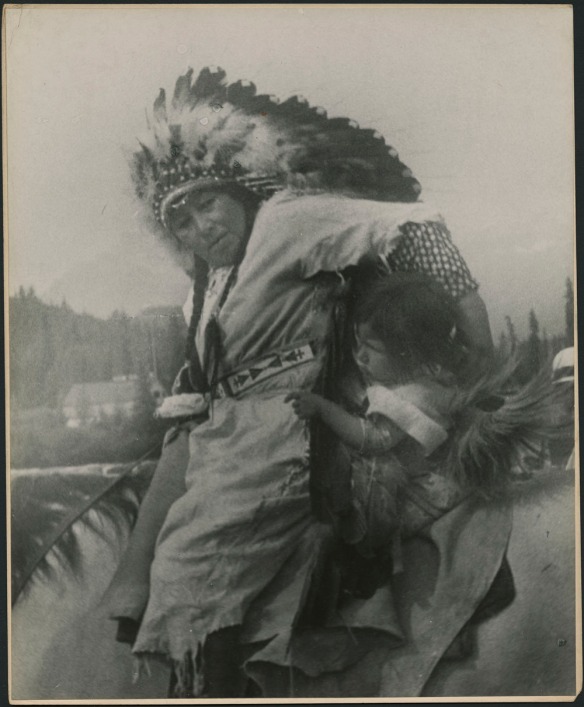

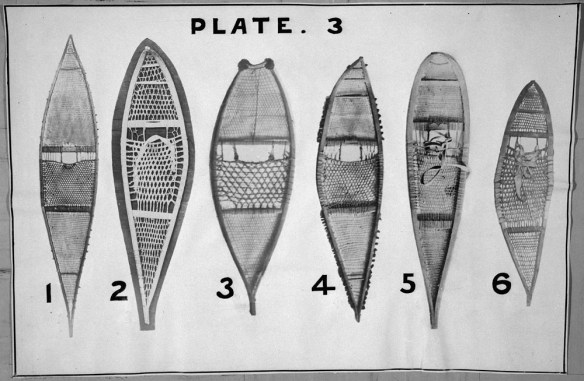

In the early research period, Richard Wagamese’s book, Indian Horse, hit a chord and resonated with the team. Michael Robidoux’s book on Indigenous hockey, Stickhandling Through the Margins, motivated us to ensure that space be put aside for the full integration of Indigenous voices in the game, whether from the early leadership of Thomas Green, or through the artwork of Jim Logan to spark discussion of hockey in society.

Drawing on Carly Adams’ book, Queens of the Ice, the museum acquired and exhibited a rare Hilda Ranscombe jersey. We also read the footnotes in Lynda Baril’s Nos Glorieuses closely, and as a result were able to secure a number of important artifacts that were still in private collections, including a trophy awarded to Berthe Lapierre of the Montréal Canadiennes in the 1930s. And when we read about Hayley Wickenheiser skating to school in the drainage ditches along the roadside, building up the muscles that made her a leader in the sport, on and off the ice, we put her story near the centre of the exhibition.

A few of our favourite books found their way directly into the museum cases, to tell their own stories.

For instance, where we highlighted the role of the team-behind-the-team, we gave Lloyd Percival’s book The Hockey Handbook a central spot in the case. Gary Mossman’s recent biography of Percival was a big influence here, and in particular, I was fascinated by the powerful impact Percival’s book had on how hockey players and coaches approached the game. Imagine a time when players ate more red meat and drank beer the night before a game, rather than following Percival’s advice to eat yogurt and fresh fruit! And yet it was not that long ago! Apparently the book was taken up by Soviet hockey coach Anatoli Tarasov, and we saw its impact on the ice in 1972. Percival also had an interesting perspective on burnout, or “staleness” as he called it—a theory that has application for both on- and off-ice players.

Stephen Smith, author of Puckstruck, lent the museum collectible and fun cookbooks that teams published—this spoke to the overlap between popular fan culture and the down-to-earth and very practical realities of nutrition in high-performance sport.

The Museum of Manitoba loaned bookmarks that had been distributed to school kids by the Winnipeg Jets, each with a hockey player’s personal message about the importance of literacy in everyday life. These were displayed next to the hockey novels and comic books from LAC.

The exhibition team wondered about how to tackle prickly issues like penalties, violence and controversy. Then we hit on the most natural of all approaches—let the books and newspaper articles tell the stories! So next to an official’s jersey, you will find our suggested reading on the ups and downs of life as a referee, Kerry Fraser’s The Final Call: Hockey Stories from a Legend in Stripes. In the press gallery section, the visitor gets a taste for the ways that sports journalists have made their mark on the game. Next to a typewriter, an early laptop and Frank Lennon’s camera, we placed Russ Conway’s book Game Misconduct: Alan Eagleson and the Corruption of Hockey.

To capture the importance of youth literacy, we carefully chose books that we tested ourselves for readability.

C’est la faute à Ovechkin by Luc Gélinas, Éditions Hurtubise inc., 2012 (AMICUS 40717662)

La Fabuleuse saison d’Abby Hoffman by Alain M. Bergeron, Soulières, 2012 (AMICUS 40395119)

Hockeyeurs cybernétiques by Denis Côté, Éditions Paulines, 1983 (AMICUS 3970428)

Literacy became a thread running through the exhibition, in ways big and small. Thanks to all the librarians who helped us get our hands on these books! It may be too ambitious, but I continue to cherish the hope that the exhibition and this blog will inspire you to pick up a book, visit a library, and enjoy the game as much as we did.

Wishing to bring a fresh read to the sport, Jenny Ellison and I are editing a group of new essays on the sport, to be published in 2018 (Hockey: Challenging Canada’s Game — Au-delà du sport national) Check it out!

Do you have a favourite book about hockey? Let us know in the comments.

Jennifer Anderson was co-curator of the exhibition “Hockey” at the Canadian Museum of History. Currently, she is an archivist in the Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada.