This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

By Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour

Tom Cogwagee Longboat’s name is associated with speed, athleticism, determination, courage and perseverance. His Onondaga name, “Cogwagee,” translates as “all” or “everything.” Facts, stories and photographs of his life have been collected, published and examined over the past century, in an attempt to capture, recreate and demystify his life.

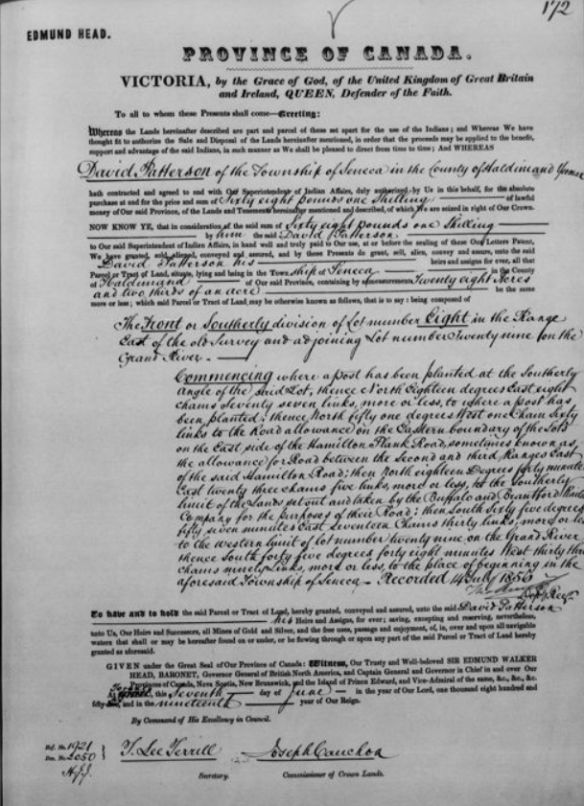

Thomas Charles Cogwagee Longboat was born to George Longboat and Elizabeth Skye on July 4, 1886 (some sources have June 4, 1887). He was Wolf Clan of the Onondaga Nation from Six Nations Territory and lived a traditional life of the Haudenosaunee (Longhouse). At the age of 12 or 13, Longboat was forcibly sent to the Mohawk Institute Residential School, an Anglican denominational and English-language school, which operated from 1823 and closed in 1970. This experience did not go well for him and his fellow First Nations students, who were forced to abandon their language and beliefs to speak English and practice Christianity. Longboat reacted by escaping the school and running home. He was caught and punished, but then escaped a second time, with the foresight to run to his uncle’s farm, where he would be harder to find. This proved successful and marked the end of Longboat’s formal education. He worked as a farm labourer in various locations, which involved travelling great distances on foot.

Longboat began racing as an amateur in 1905. He won the Boston Marathon on April 19, 1907, in two hours, 24 minutes and 24 seconds, shaving nearly five minutes off the previous record for the world’s most prestigious annual running event. With this incredible race, he brought tremendous pride and inspiration to Indigenous peoples and Canadians. The following article was published the day after he won the marathon:

“The thousands of persons who lined the streets from Ashland to the B.A.A. were well repaid for the hours of waiting in the rain and chilly winter weather, for they saw in Tom Longboat the most marvelous runner who has ever sped over our roads. With a smile for everyone, he raced along and at the finish he looked anything but like a youth who had covered more miles in a couple of hours than the average man walks in a week. Gaining speed with each stride, encouraged by the wild shouts of the multitude, the bronze-colored youth with jet black hair and eyes, long, lithe body and spindle legs, swept toward the goal.

Amid the wildest din heard in years, Longboat shot across the line, breaking the tape as the timers stopped their watches, simultaneously with the clicking of a dozen cameras, winner of the greatest of all modern Marathon runs. Arms were stretched out to grasp the winner, but he needed no assistance.

Waving aside those who would hold him, he looked around and acknowledged the greetings he received on every side. Many pressed forward to grasp his hand, and but for the fact that the police had strong ropes there to keep all except the officials in check, he would have been hugged and squeezed mightily. Then he strode into the club, strong and sturdily.” (The Boston Globe, April 20, 1907)

A year after winning that race, Longboat competed in the marathon at the 1908 Olympics in London, England. He collapsed and dropped out at 32 kilometres, unable to finish the 42.2 km race. He then turned to professional running, and in 1909 received the title of Professional Champion of the World at a Madison Square Garden race in New York City.

A page from the 1911 census listing Thomas C. Longboat and his wife Loretta [Lauretta], in York County, Ontario. His profession is listed as “runner.” (e002039395)

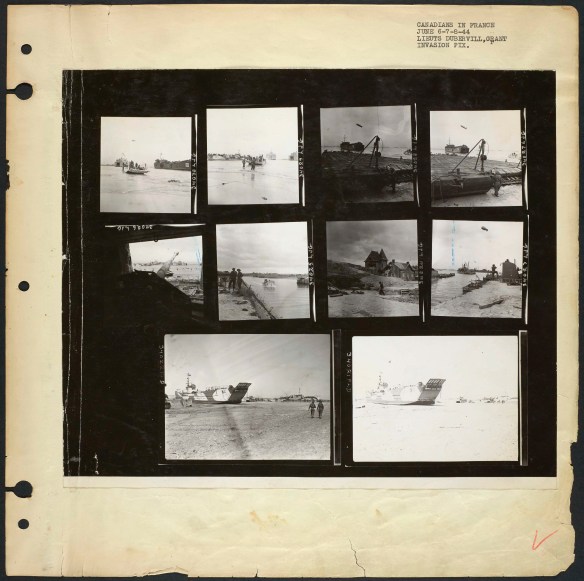

Private Tom Longboat, the Onondaga long-distance runner, buying a newspaper from a French boy, June 1917. (a001479)

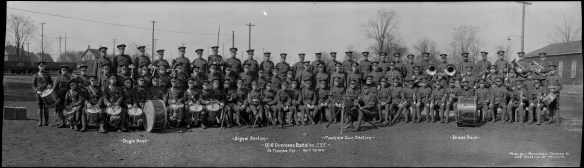

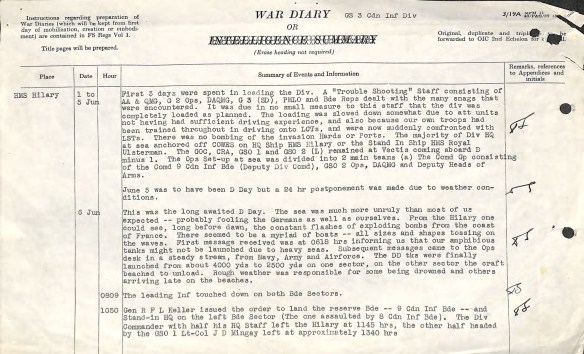

In 1916, Longboat went overseas as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force to fight in the First World War. He employed his natural talent and served as a dispatch runner. Longboat was mistakenly declared dead in the battlefields of Belgium, after being buried in rubble as a result of heavy shelling. His wife, Lauretta Maracle, a Kanienkenha:ka (Mohawk) woman, whom he had married in 1908, believed him to be deceased and remarried. Longboat subsequently married Martha Silversmith, an Onondaga woman, with whom he had four children. He continued his military career, serving as a member of the Veterans Guard in the Second World War while stationed at a military camp near Brantford, Ontario. The Longboat family settled in Toronto. Upon his retirement from employment with the City of Toronto, Longboat moved back to Six Nations. He passed away on January 9, 1949.

In 1951, he received posthumous recognition with the establishment of the prestigious Tom Longboat Trophy. The trophy is awarded annually to Indigenous athletes who exemplify the hard work and determination they put forth in their chosen endeavours. The original trophy remains at Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in Calgary, with a travelling replica held by the Aboriginal Sports Circle in Ottawa. In 1955, he was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame and the Indian Hall of Fame.

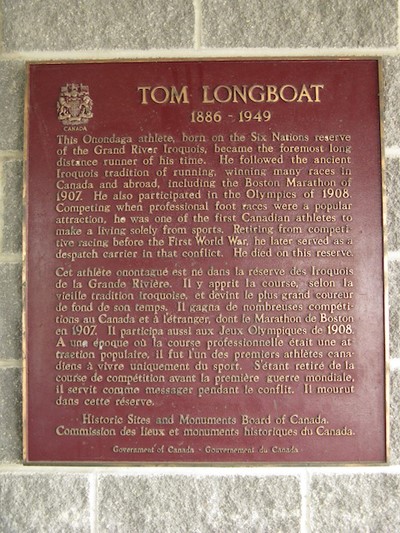

A Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaque honouring Tom Longboat, located at 4th Line Road, Six Nations Grand River Reserve, Ohsweken, Ontario. (Photo courtesy of Parks Canada)

Tributes in recognition of Longboat’s achievements continue today in many forms. A Government of Canada plaque was erected in his honour in 1976 at 4th Line Road, Six Nations, Ohsweken, Ontario. In 1999, Maclean’s magazine recognized him as the top Canadian athlete of the 20th century. Canada Post issued a stamp in 2000 commemorating his winning time. In Ontario, the Tom Longboat Day Act, 2008 designated June 4 as “Tom Longboat Day.” Tom Longboat Corner in Six Nations, a Tom Longboat Trail in Brantford, Ontario, a Tom Longboat Lane in Toronto, and a Tom Longboat Junior Public School in Scarborough, Ontario. There is also a Longboat Hall at 1087 Queen Street West in Toronto, the location of the YMCA where he trained. A statue of Longboat entitled “Challenge and Triumph,” created by David General, and an exhibit about him are on display at the Woodland Cultural Centre at Six Nations. Most recently, a children’s book about his life called Meet Tom Longboat was published in 2019.

Tom Cogwagee Longboat’s life and accomplishments are both fascinating and inspiring. To learn more about him, listen to our podcast, “Tom Longboat is Cogwagee is Everything,” which includes additional information. Also check out the Tom Longboat Flickr album.

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.

Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour is a project archivist in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division of the Public Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=519&h=142)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg?w=519&h=142)