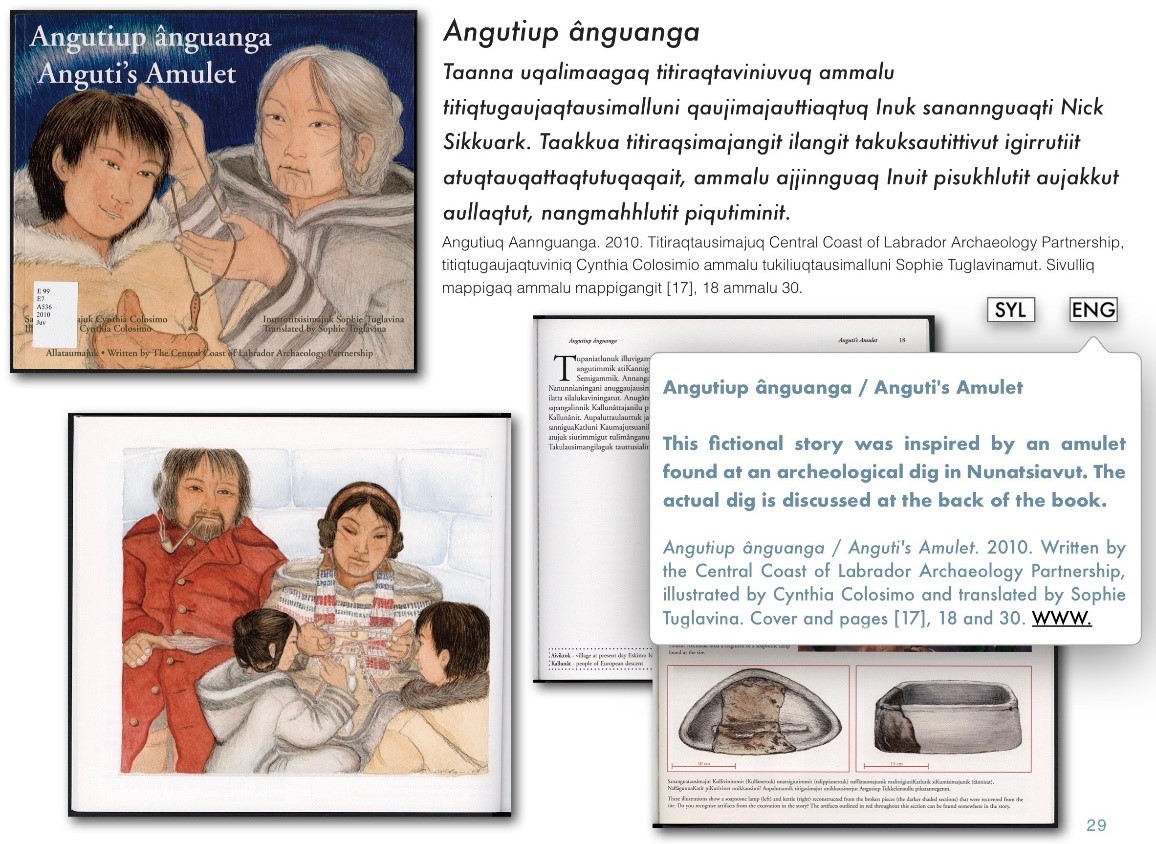

This blog is part of our Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada series. To read this blog post in Cree syllabics and Standard Roman Orthography, visit the e-book.

Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada is free of charge and can be downloaded from Apple Books (iBooks format) or from LAC’s website (EPUB format). An online version can be viewed on a desktop, tablet or mobile web browser without requiring a plug-in.

By Samara mîkiwin Harp

If Only We Could Have Our Stories Told, by Jane Ash Poitras, 2004 (e010675581)

This mixed-media work by Cree artist Jane Ash Poitras features a group of children at residential school awaiting the missionaries’ teachings. Church and Crown purposefully disregarded our teachings and stories in an effort to assimilate us. “If only we could have our stories told” expresses the desire of our people to reclaim our language and culture that were taken from us.

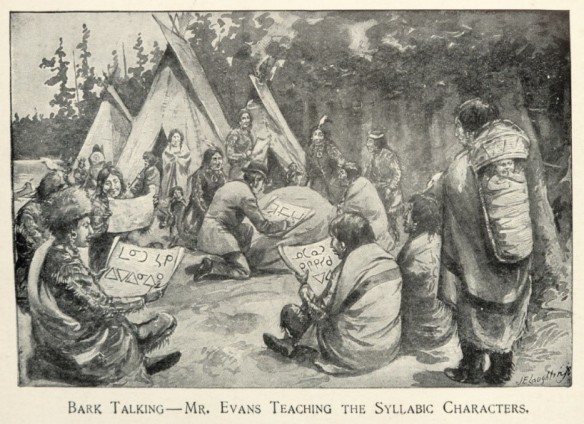

“In all the oral accounts of the origins of the Cree syllabary it was told that the missionaries learned Cree syllabics from the Cree. In the [Wes] Fineday account Badger Call was told by the spirits that the missionaries would change the script and claim that the writing belonged to them.” [Please note that in the literature on the subject, Badger Call is also known as Calling Badger and Badger Voice.]

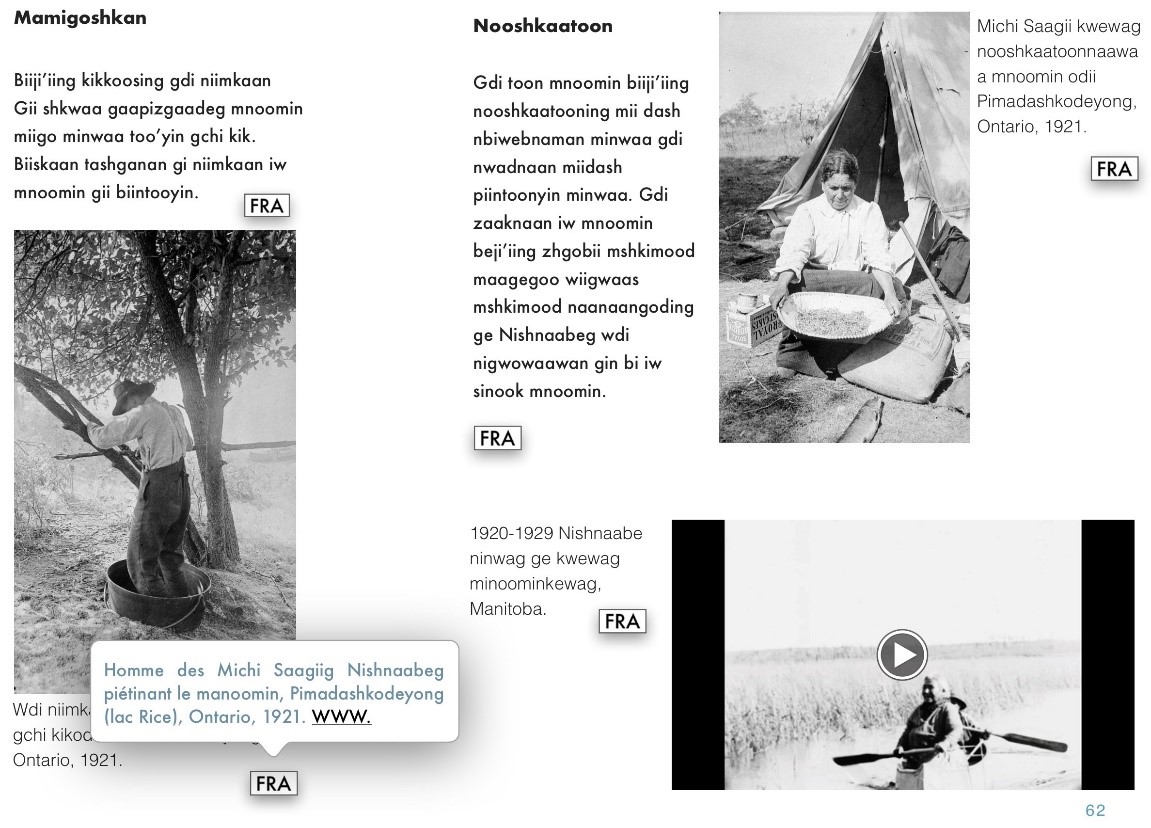

Preliminary research shows that it is generally accepted that the Reverend James Evans (1801–1846) created Cree syllabics sometime during the early 19th century. In 1828, while teaching in Anishinaabe (Ojibway) country, Evans was immersed in “Ojibway” and became proficient in the language. In August 1840, Evans was stationed at a mission in the Cree-speaking community of Norway House (in present-day Manitoba). Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe language) and nêhiyawêwin (the Cree language) are in the Algonquian language family and are somewhat similar in their use of sounds.

James Evans recording syllabics on birch bark with a group of nêhiyawak (people of the Cree nation), unknown date, illustration in Egerton R. Young, The Apostle of the North, Rev. James Evans, New York, Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Co., [1899], plate between pages 190 and 191 (OCLC 3832900)

Replica of the Cree syllabary chart developed ca. 1840, published in Egerton R. Young, The Apostle of the North, Rev. James Evans, New York, Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Co., [1899], p. 187 (OCLC 3832900)

The first hymn written and printed in Cree syllabics, ca. 1840, published in Egerton R. Young, The Apostle of the North, Rev. James Evans, New York, Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Co., [1899], p. 193 (OCLC 3832900)

Further research suggests that Evans conceived his ideas for the syllabary from other sources that he never credited. According to the British and Foreign Bible Society annual report in 1859, “The idea he derived from an Indian Chief.”

Additional evidence pointing to the influence of nêhiyawak (people of the Cree nation) in the creation of syllabics has also been proposed. For example, the four-directional nature of the syllabics hints at a Cree influence, as the Cree ways of knowing utilize the four directional teachings. We also find evidence in missionary reports that “hieroglyphics” were “painted upon” pieces of birch bark before the arrival of the missionaries: “It was not until Missionaries were sent among the Cree Indians, that any other mode of conveying ideas, except orally, existed; if we exclude the rude hieroglyphics painted upon large pieces of birch bark.” Furthermore, nêhiyawak were known to have used birch bark for creating birch bark bitings. Using the eye teeth, the artist bites designs into thin pieces of birch bark, creating perfectly symmetrical designs when unfolded. This ancient art form can be achieved through a wide variety of folds. A typical folding pattern starts with a square piece of bark, which is folded into a right angle, followed by a complementary-angle fold that, when completed, results in what mathematicians refer to as perfect symmetry. This pre-contact style of art uses spatial thinking and reasoning to create records of ceremony, stories, events and later beadwork patterns. Similarly, Cree syllabics can be arranged in perfect symmetry. Cree oral history says that when the syllabics were gifted to the people from the spirit world, the syllabics were on birch bark.

It is my belief that today’s syllabics are ultimately the result of collaboration between numerous Indigenous people and James Evans. However, to delve deeper into their origins, learners must enter into the world of Cree oral history. My research into oral histories available online uncovered the story of mistanâkôwêw (Calling Badger), a spiritual man from the west in the area now known as Stanley Mission, Saskatchewan. In this account, mistanâkôwêw entered the spirit world and returned with the knowledge of Cree syllabics. A similar story exists about a man named mâcîminâhtik (Hunting Rod) who lived in the east. Fortunately, there are some recordings by Winona Wheeler and Wes Fineday, available online through the CBC, which discuss the Cree origin stories on syllabics.

Additional Resources

- CBC interactive story: A question of legacy: Cree writing and the origin of the syllabics, Wes Fineday on CBC Radio’s “Trail’s End,” March 6, 1998 and, Winona Wheeler speaks on CBC Radio about the creation story of syllabics

- Syllabics and SRO (Standard Roman Orthography): Two sides of the same coin (and Plains Cree Syllabics chart, y-dialect), Cree Literacy Network

- SRO (Woods) Cree Syllabic Chart, th-dialect, Lac La Ronge Indian Band

- Downloads for a Cree syllabics keyboard, Language Geek

- SRO to syllabics converter for Cree (n-dialect, th-dialect and y-dialect), Eddie Santos

- itwêwina: Plains Cree Dictionary, Alberta Language Technology Lab, in collaboration with the First Nations University and Maskwacîs Education Schools Commission

- Winona Stevenson (Wheeler), “Calling Badger and the Symbols of the Spirit Language: The Cree Origins of the Syllabic System,” Oral History Forum, Vol. 19–20 (1999–2000), p. 21

- John McLean, James Evans, Inventor of the Syllabic System of the Cree Language, Toronto: W. Briggs, Montréal: C.W. Coates, [1890?], p. 167

- British and Foreign Bible Society, Fifty-fifth Report, 1859, p. 304

- James Evans, Cree Syllabic Hymn Book, Toronto: Bibliographical Society of Canada, 1954, back cover (OCLC 1152061)

- To learn more about birch bark bitings, see Wigwas: Bark Biting by Angelique Merasty: June 30–July 24, 1983, Angelique Merasty and Mary Zoccole, Thunder Bay, Ontario: [The Centre, 1983] (OCLC 35944618)

Samara mîkiwin Harp was an archivist with the Listen, Hear Our Voices initiative at Library and Archives Canada. She now works in Woods Cree language revitalization and is further pursuing archival studies. Samara grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, with Cree roots in both the Southend and Pelican Narrows areas of Treaty 6 in northern Saskatchewan. The first of her father’s family arrived in Ontario in the 1800s from Ireland and England.

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg?w=584&h=365)

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg)