![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

By Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour

Kahentinetha Horn, of the Kanien’kehá:ka (People of the Flint), will be featured in an upcoming Library and Archives Canada (LAC) Indigenous podcast, in which a selection of events from her life will be highlighted. LAC holds a diverse collection of archival materials that feature Kahentinetha (or Kahn-Tineta) Horn. These include photographs, audio-visual material, film and correspondence. The materials document her vision, her resilience and her aspirations with respect to bringing Onkweonwe (First Nations) issues to the forefront.

Her name, Kahentinetha, translates to “flying over the land.” She has definitely lived, and continues to live, by her name. I am fortunate to have known Kahentinetha when I was growing up in Kahnawake. Kahentinetha was a vibrant force. She was tall, thin and athletic in stature, and had refined Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) thick straight jet-black hair. In the opinion of many—myself included—she was in a class by herself. Her speech was concise, her voice always clear, never wavering. She had an inquisitive mind and was always ready to debate and bring new light to topics and situations of the time. As part of the podcast team, I gained deeper insight into—and greater appreciation of—her incredible life.

In February 2020, Kahentinetha and her daughter Waneek visited LAC to view archival materials. These materials included correspondence written by Kahentinetha to Maryon Pearson, wife of Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, to the Minister and the deputy ministers of Indian Affairs, and to other federal government officials of the time, as well as internal correspondence and reciprocal letters. Also, among the textual papers were Kahnawake Mohawk Band Council correspondence and documentation that included a poignant Band Council resolution against Kahentinetha, which was never carried out.

Caughnawaga [Kahnawake] reserve near Montréal [left to right: Kahentinetha Horn (née Delisle, grandmother of Kahentinetha Horn), Joseph Assenaienton Horn, Peter Ronaiakarakete Horn (Senior) holding Peter Horn (Junior), Theresa Deer (née Horn), Lilie Meloche (née Horn), unknown, Andrew Horn, unknown], c. 1925 (e010859891)

Kahentinetha remembers her father as a definitive influence in her early life. He stressed to her the need to use the Kanien’kehá language at all times. She continues to pursue this linguistic endeavour by collaborating with Kanehsatà:ke (Kanien’kehá:ka Oka) elders. Working with them, she documents the pronunciation and spelling of complex expressions that otherwise would be lost forever.

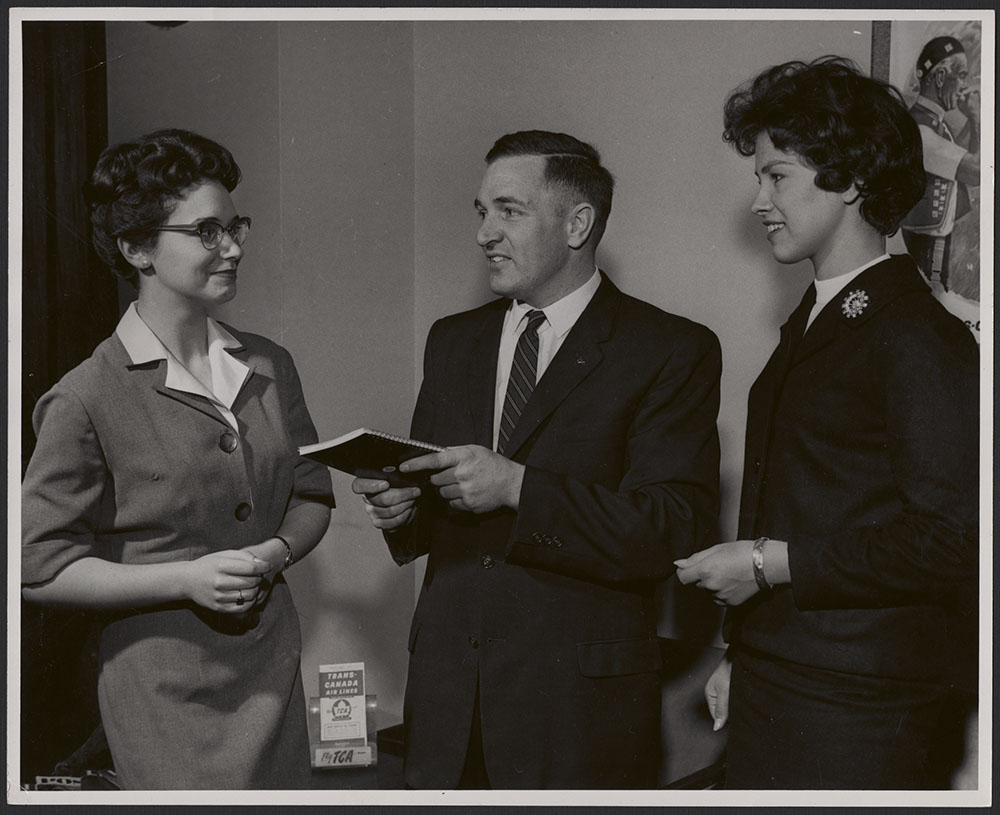

Carnival Queen Kahentinetha Horn tries her hand at the controls of a Viscount aircraft. A newcomer to Trans-Canada Airlines (TCA), she was crowned Queen of the Sir George Williams College Winter Carnival in Montréal just one week after she joined TCA. Kahentinetha is wearing buckskin regalia made by her aunt Francis Dionne (nee Diabo). (e011052443)

Kahentinetha was born in Brooklyn, New York, like many Kahnewakeronon, as her father needed to be close to where the iron work was. The family later returned to Kahnawake. Her father died tragically on the job, just a half hour from Kahnawake, at the Rouses Point Bridge, which links New York State and Vermont across Lake Champlain. She lived through the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s. This canal permanently separated the community from its natural shoreline.

Kahentinetha studied economics at Sir George Williams University in Tio’tia:ke (Montreal). This afforded her the opportunity to work abroad, in Paris. She also studied economics at McGill University. This presented an opportunity to travel with two other students to Havana in December 1959, to observe the people of that country celebrating the first anniversary of the Cuban Revolution.

Officer Harold Walker introduces Kahentinetha Horn to receptionist Pierrette Desjardins as Kahentinetha starts her first day of employment at Trans-Canada Airlines. (e011311516)

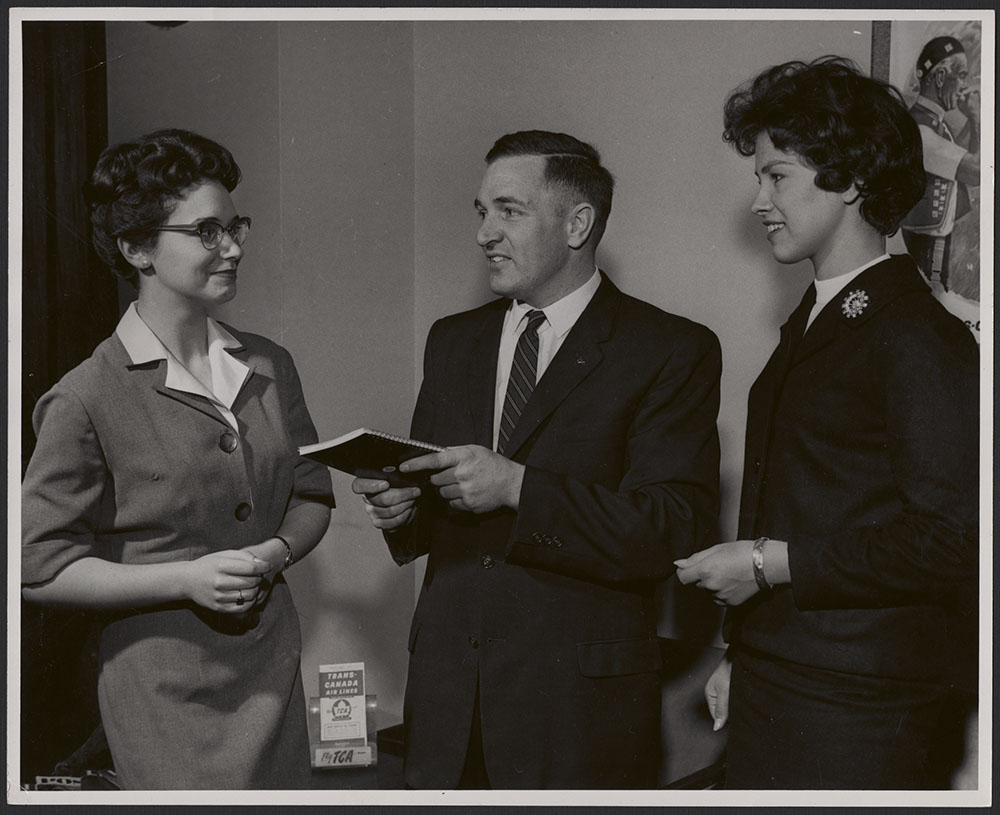

Kahentinetha’s resume includes employment as a secretary with Trans-Canada Airlines (name changed to Air Canada in 1965) and at the Power Corporation. Her career in fashion involved daily modeling at the Canada Pavilion during the Expo 67 World’s Fair in Montréal, Quebec, and being photographed for fashion advertisements in magazines. She also acted in film and television commercials. In 1973, she was employed as a public servant at the Department of Indian Affairs, in the National Capital Region. In the summer of 1990, while she was in the midst of doing scholarly research on Kahnawake, Kanehsatà:ke and Akwesasne, the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance (Oka Crisis) had reached a critical point. She knew her mission was to support and defend the Kanehsatà:ke land. She went to Kanehsatà:ke in July 1990 with all four of her daughters and remained there until September 26. On that date, the Canadian army entered the area, dismantled the barricades, and arrested the remaining supporters, including Kahentinetha and her two youngest daughters, Waneek and Kaniehtiio.

Crowd in front of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67. Date: 1967. (e001096693)

Beginning on February 21, 1991, Kahentinetha participated as an individual witness in the public hearing for the House of Commons that resulted in the publication of the Fifth Report of the Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs (May 1991). She followed this with a presentation to the Commissioners at the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), in Kahnawake, in May 1993. The RCAP hearings were held across Canada to collect information, evidence and counsel, as well as to uncover issues on which action was required. Most recently, she was involved and took part in welcoming the Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders on their arrival in Tyendinaga on February 20, 2020.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), Kahnawake hearings. Seated are Kahente Horn-Miller (daughter), Kahentinetha Horn and Dale Dionne. Standing is Mary Sillett (Inuit, Nunatsiavut – Labrador), RCAP Commissioner. Kahnawake site, May 1993. (e011301811)

Of the many Kanien’kehá:ka elders Kahentinetha has known, the late Louis Karonhiaktajeh (Edge of the Sky) Hall gave her special insight and inspiration. Hall was a traditionalist, activist, writer and painter born in Kahnawake in 1918, who died in 1993 at age 76. Hall used his natural artistic abilities to paint vivid and powerful scenes of Kanien’kehá subjects. He painted the iconic red warrior flag with the profile of a Haudenosaunee warrior in the centre. When he was elderly, she brought him into her home and cared for him. He gifted her a portrait he had painted of her. This may be the only painting that left his private collection.

Kahentinetha would regularly visit at my home, usually with several other relatives and friends, sometimes from other places. My mother, Josephine Kaientatie (Things all over), always had a meal ready, and no one ever left hungry. One of my vivid memories of Kahentinetha was her arriving in a white leather fringed jacket, matching mini-skirt and white boots. It was the sixties, and she was able to carry off this look because she had confidence. Stories told in these visits were usually a combination of political and social issues. When the topics were mixed with Kanienkeha:ka humour, an abundance of laughter would fill our home.

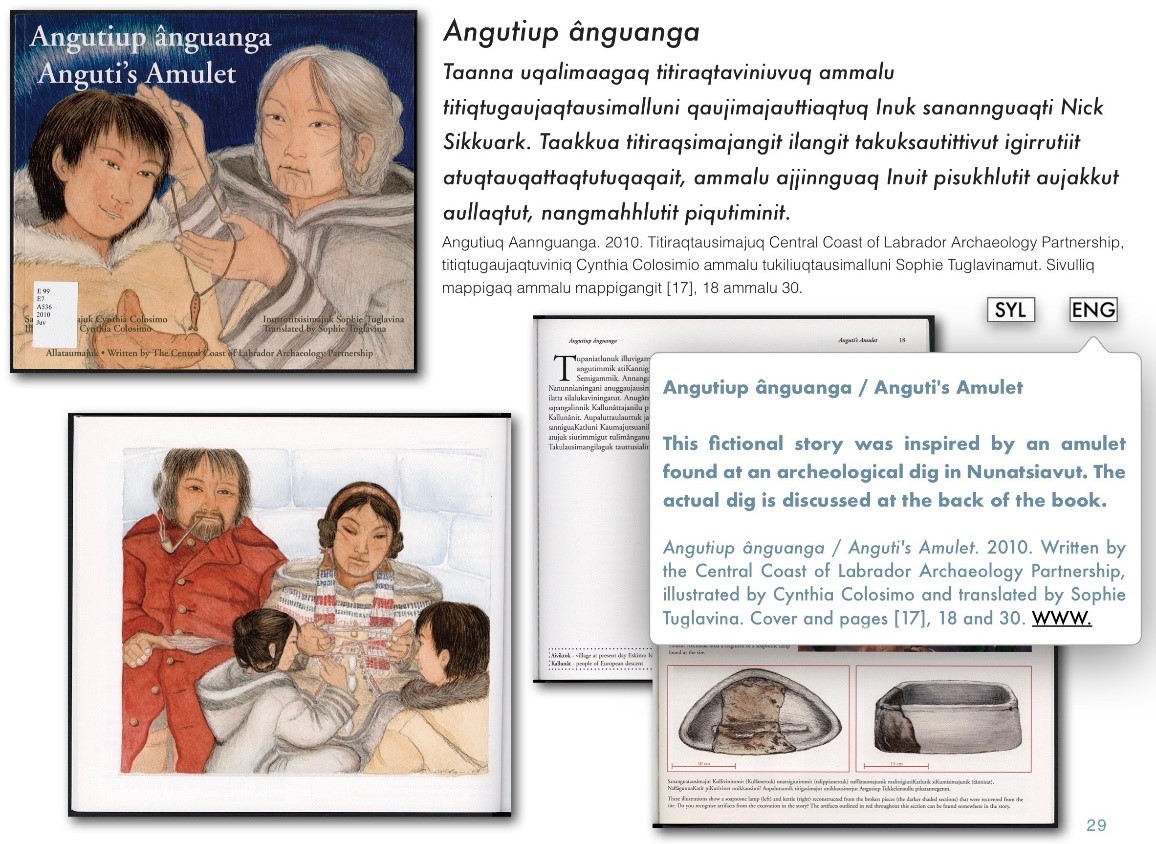

There are other, less serious, memories, such as those from the summer of 1971. Kahentinetha had just purchased her first car, a new-edition Ford Pinto. Kahentinetha took my mother, her baby daughter, Ojistoh, and me on a road trip to visit our cousins. Heading west to two Kanien’kehá:ka communities, Tyendinaga and Ohsweken, of the Six Nations in Ontario, we sped down Highway 401 in our shiny red faux Cadillac.

Of great pride to Kahentinetha are her daughters, all of whom have pursued their own ambitions with great success. Her eldest, Ojistoh, is a medical doctor; Kahente holds a PhD and is a professor at Carleton University; Waneek an Olympic athlete and a Pan American Games gold medalist; and the youngest, Kaniehtiio, works in many facets of the media including roles in film and television.

Kahentinetha Horn, Hilda Kaheratahawi Nicolas and Nancy Kanahstatsi Beauvais at the Kanesatake Language and Cultural Centre, March 6, 2020. Photo by Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour.

Kahentinetha now spends her time at her home on the east side of Kahnawake, not far from where the Lachine Rapids flow. She enjoys tending her vegetable garden, with the help of her many grandchildren. A stream of water flows by the edge of her land. Through her life, she has influenced, and connected with people of many cultures from around the world. She continues her contributions by providing guidance and sharing knowledge of Haudenosaunee culture, language and history with those who seek it. I am thankful for this assignment, which enabled me to reconnect with her. She was and did so much more than I remembered or knew.

You can also listen to our Kahentinetha Horn podcast (Part 1 and Part 2) and flip through our Kahentinetha Horn Flickr album.

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.

Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour is a project archivist in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division of the Public Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg?w=584&h=365)

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)