By Beth Greenhorn in collaboration with Tom Thompson

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) launched Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada to coincide with the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30, 2021. The essays in this first edition of the interactive multilingual e-book featured a wide selection of archival and published material ranging from journals, maps, newspapers, artwork, photographs, sound and film recordings, and publications. Also included are biographies for each of the authors. Many recorded a personalized audio greeting for their biography page, some of which are spoken in their ancestral language. The essays are diverse and, in some cases, quite personal. Their stories challenge the dominant narrative. In addition to authors’ biographies, we included biographical statements by the translators in recognition of their expertise and contributions.

The Nations to Nations e-book was created as part of two Indigenous initiatives at LAC: We Are Here: Sharing Stories (WAHSS) and Listen, Hear Our Voices (LHOV). The essays were written by Heather Campbell (Inuk), Anna Heffernan (Nishnaabe), Karyne Holmes (Anishinaabekwe), Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour (Kanien’kehá:ka), William Benoit (Métis Nation) and Jennelle Doyle (Inuk) in LAC’s National Capital Region office. They were joined by Ryan Courchene (Métis-Anichinabe), from LAC’s regional office in Winnipeg, and Delia Chartrand (Métis Nation), Angela Code (Dene) and Samara mîkiwin Harp (nêhiyawak), archivists from the LHOV initiative.

This edition features the following First Nations languages and/or dialects: Anishinaabemowin, Anishinabemowin, Denesųłiné, Kanien’kéha, Mi’kmaq, nêhiyawêwin and Nishnaabemowin. Essays related to Inuit heritage are presented in Inuttut and Inuktitut. Additionally, the Inuit heritage content is presented in Inuktut Qaliujaaqpait (Roman orthography) and Inuktut Qaniujaaqpait (Inuktitut syllabics). The e-book presents audio recordings in Heritage Michif of select images in essays pertaining to the Métis Nation.

The development of this type of publication was complex. It presented technical and linguistic challenges that required creativity and flexibility. But the benefits of the Indigenous-led content outshine any of the complications. Given the space and time, the authors reclaimed records of relevance to their histories, offering fresh insights through their interpretations. The translators brought new meanings to the records, describing most, if not all, of them for the first time in First Nations languages, Inuktut and Michif.

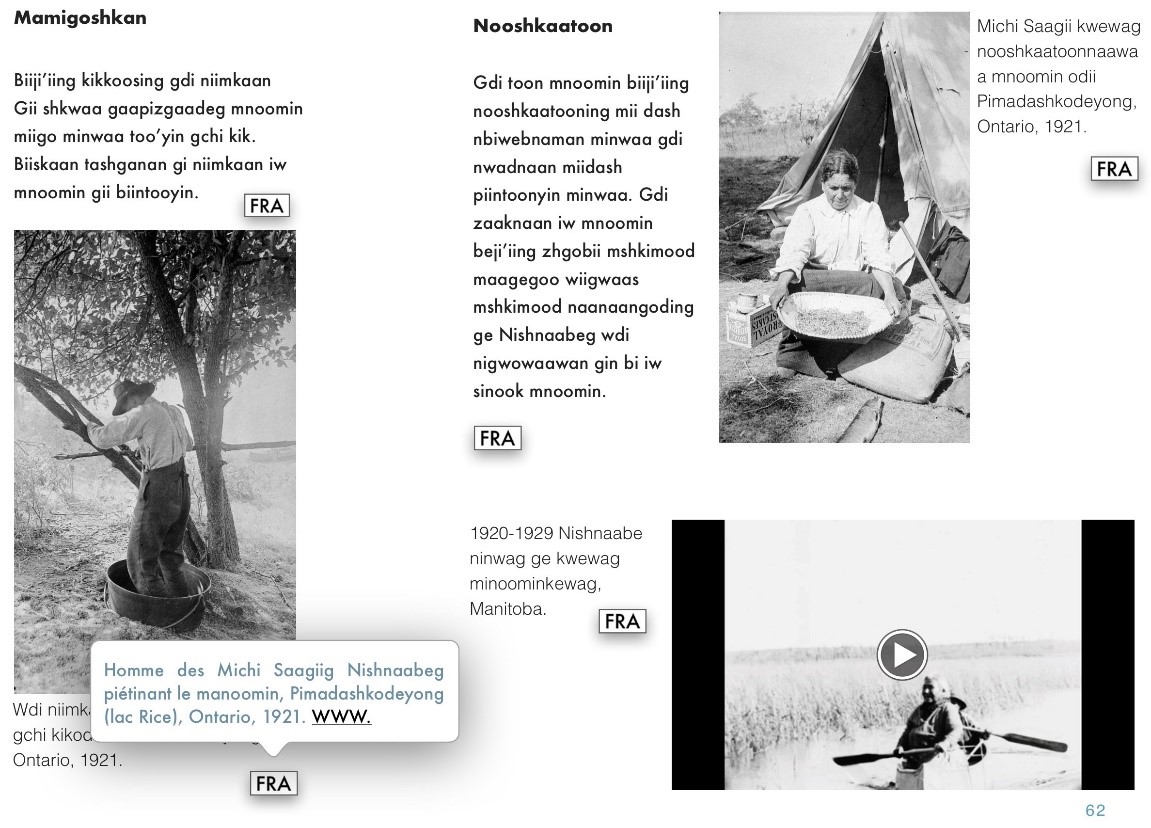

Describing her experience while researching and writing her essay regarding manoominikewin (the wild rice harvest) of the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg (Mississauga Ojibwe), archivist Anna Heffernan wrote: “I hope that people from Hiawatha, Curve Lake, and the other Michi Saagiig communities will be happy and proud to see their ancestors in these photos, and to see them represented as Michi Saagiig and not just ‘Indians’.”

Page from “Manoominikewin: The Wild Rice Harvest, a Nishnaabe Tradition” by Anna Heffernan, translated into Nishnaabemowin by Maanii Taylor. Left image: Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg man tramping manoomin, Pimadashkodeyong (Rice Lake), Ontario, 1921 (e011303090); upper-right image: Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg woman winnowing manoomin, Pimadashkodeyong (Rice Lake), Ontario, 1921 (e011303089); lower-right image: silent film clips featuring Ojibway men and women from an unidentified community harvesting manoomin, Manitoba, 1920–1929 (MIKAN 192664)

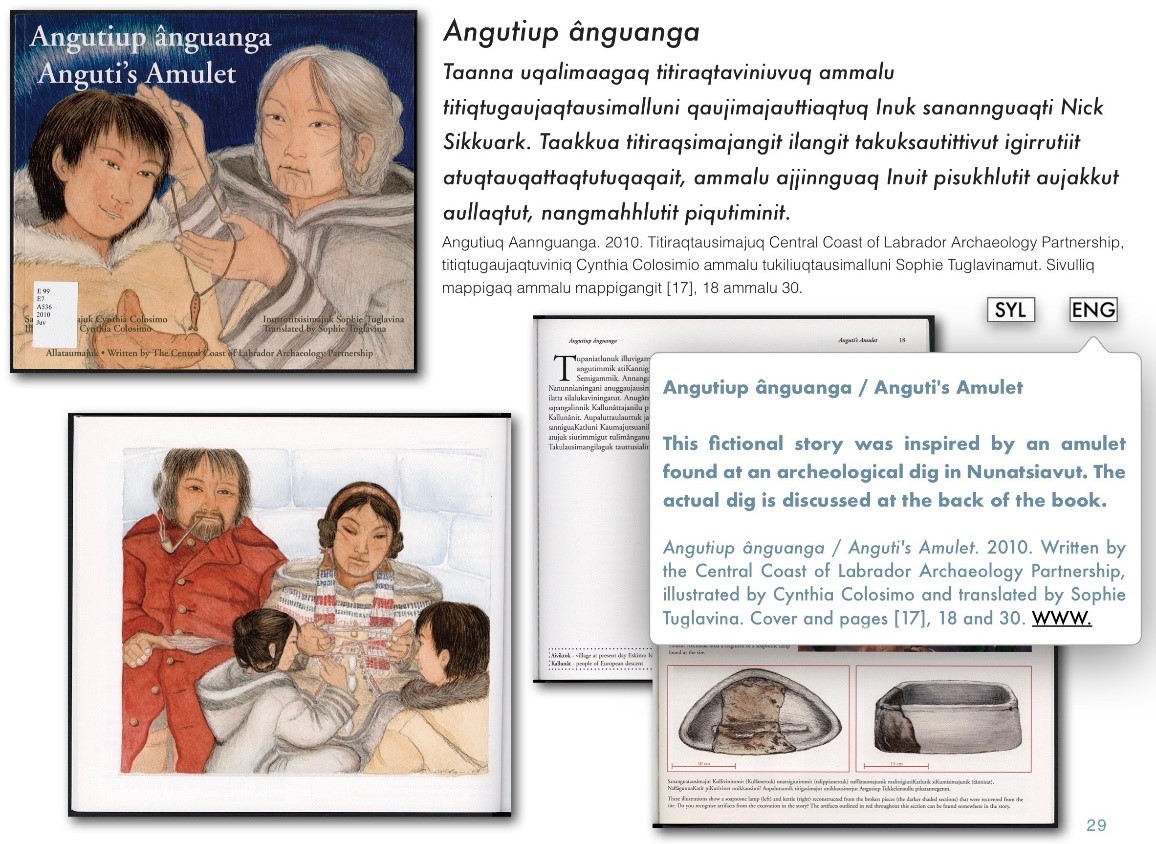

Reflecting on her experience, archivist Heather Campbell described the positive impact of the process:

“So often when we see something written about our communities, it is not written from the perspective of someone who is from that community. To be asked to write about Inuit culture for the e-book was an honour. I was able to choose the theme of my article and was trusted to do the appropriate research. As someone from Nunatsiavut, to be given the opportunity to write about my own region, knowing other Nunatsiavummiut would see themselves reflected back, was so important to me.”

Page from “Inuktut Publications” by Heather Campbell, translated into Inuktut Qaliujaaqpait by Eileen Kilabuk-Weber, showing selected pages from Angutiup ânguanga / Anguti’s Amulet, 2010, written by the Central Coast of Labrador Archaeology Partnership, illustrated by Cynthia Colosimo and translated by Sophie Tuglavina (OCLC 651119106)

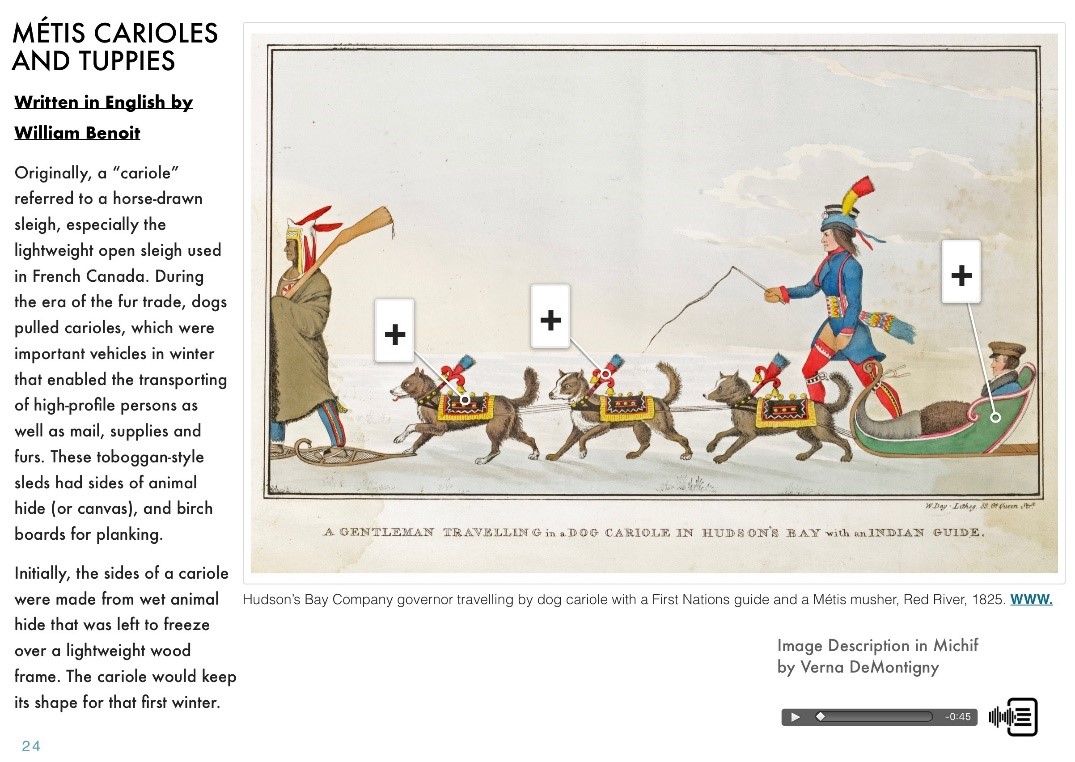

William Benoit, Internal Indigenous Advisor at LAC, wrote a number of shorter essays about Métis Nation language and heritage. While each text can be read on its own, collectively they provide insights into various aspects of Métis culture. In his words: “Although the Métis Nation represents the largest single Indigenous group in Canada, we are misunderstood or misrepresented in the broader national narrative. I appreciate the opportunity to share a few stories about my heritage.”

Page from “Métis Carioles and Tuppies” by William Benoit, with a Michif audio recording by Métis Elder Verna De Montigny. Image depicting Hudson’s Bay Company governor travelling by dog cariole with a First Nations guide and a Métis Nation musher, Red River, 1825 (c001940k)

The creation of the Nations to Nations e-book has been a meaningful undertaking and positive learning experience. Two and a half years in development, the e-book has truly been a group effort involving the expertise and collaboration of the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation authors, Indigenous language translators, and Indigenous advisors.

I am grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with so many amazing and dedicated individuals. A special “thank you” goes to the members of the Indigenous Advisory Circle, who offered their knowledge and guidance throughout the development of this publication.

As part of ongoing work to support Indigenous initiatives at LAC, we will feature the essays from Nations to Nations as blog posts. We are excited to introduce Ryan Courchene’s essay “Hidden Histories” as the first feature in this series.

Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada is free of charge and can be downloaded from Apple Books (iBooks format) or from LAC’s website (EPUB format). An online version can be viewed on a desktop, tablet or mobile web browser without requiring a plug-in.

Beth Greenhorn is a senior project manager in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division at Library and Archives Canada.

Tom Thompson is a multimedia production specialist in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg)