This blog is part of our Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada series. To read this blog post in Cree syllabics and Standard Roman Orthography, visit the e-book.

Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada is free of charge and can be downloaded from Apple Books (iBooks format) or from LAC’s website (EPUB format). An online version can be viewed on a desktop, tablet or mobile web browser without requiring a plug-in.

By Samara mîkiwin Harp

Cree syllabic typewriter created by knowledge experts from Cree communities, linguistics experts from the former Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, and Olivetti Canada Limited.

Olivetti Canada Limited, Olivetti News Magazine, June–July 1973, p. 2. (e011303083)

While the origins of Cree syllabics remain debatable, one thing is certain: Cree syllabics quickly became popular with nêhiyawak (people of the Cree nation) thanks to their accurate representation of nêhiyawêwin (the Cree language) sounds and the teaching of the syllabary at the grassroots level.

In the winter of 1841, nêhiyaw hunters and trappers from Norway House (present-day Manitoba) who set off to trade brought along hymns printed in Cree syllabics. In less than a decade, the syllabary spread to the west and east, with thousands of nêhiyawak becoming literate in syllabics. nêhiyawak usually learned how to read and write syllabics without the aid of missionaries. They taught themselves by referring to the syllabics chart. This knowledge of how to write Cree was transmitted through traders, friends and family. Some scholars say that literacy rates among the nêhiyawak surpassed those of the French and English settlers. Clearly, syllabics worked well to capture the sounds of nêhiyawêwin.

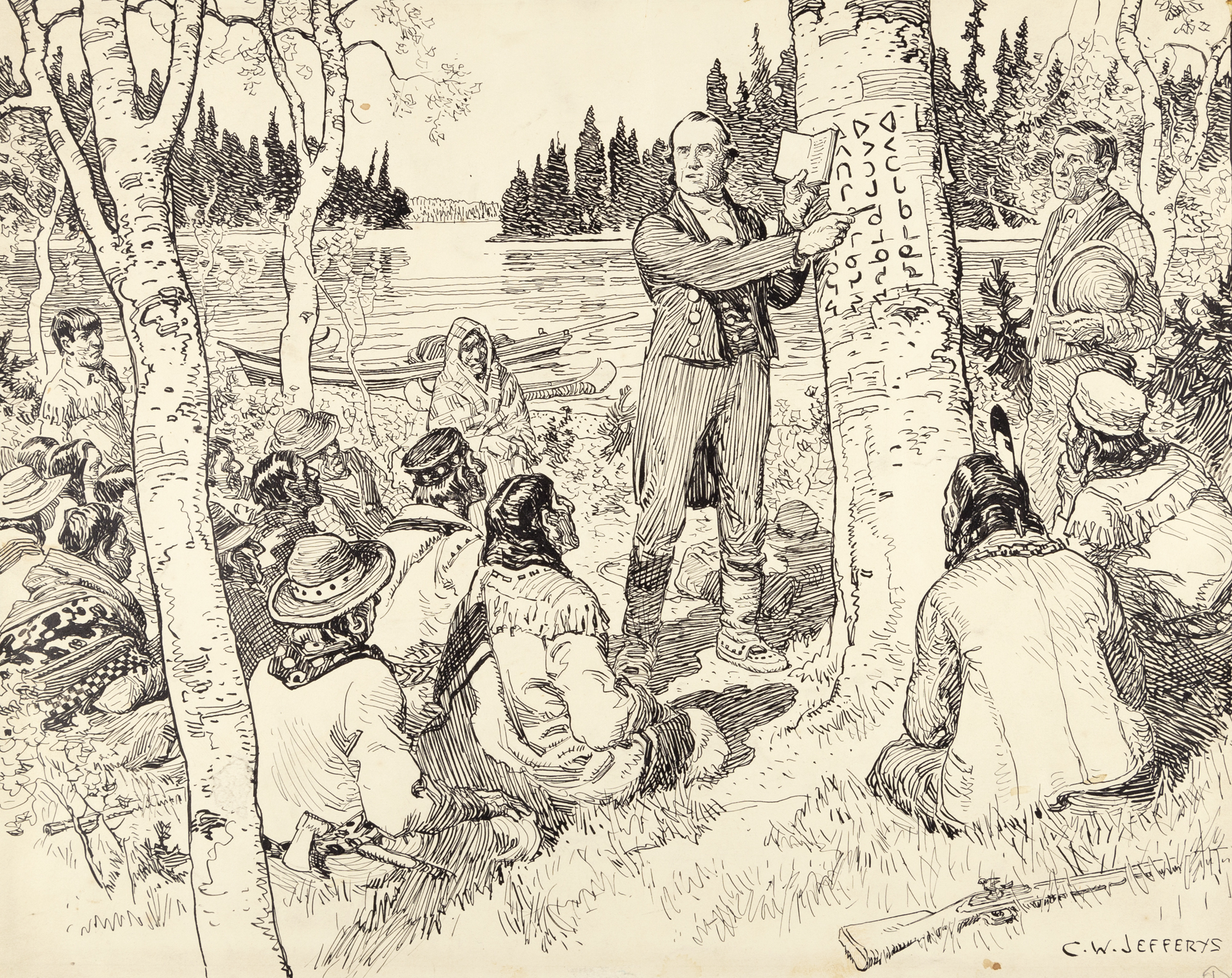

The Reverend James Evans sharing the Cree syllabics chart and hymn book that he collaborated on with Indigenous peoples. (MIKAN 2834503)

It is clear that James Evans created the physical type font (stamps for printing) for syllabics, and he played a role in helping to popularize them by printing a Cree syllabary chart and hymns in the Cree syllabary. With the help of Evans’s translation team, a book entitled Cree Syllabic Hymn Book was printed in 1841.

Unfortunately, neither Evans nor contemporary scholars gave proper credit to the Indigenous people who worked with him, an oversight rectified a century and a half later by Lorena Sekwan Fontaine:

“Evans’ translating team was largely responsible for the success of this independent printing. Team members were primarily of Aboriginal ancestry and were either bilingual or multilingual. For example, Thomas Hassell (Chippewyan) had learned fluent Cree, French and English; Henry Bird Steinhauer (Ojibway) had attended a mission school in Upper Canada and knew Greek, Hebrew, English, in addition to Cree; and John Sinclair who, as the son of an HBC officer and a Cree mother, was fluent in Cree.” (1)

Facsimile published in 1841 from the original Cree Syllabic Hymn Book, by James Evans, Norway House (present-day Manitoba), p. 23. (OCLC 1152061)

Facsimile of a hymn from the original Cree Syllabic Hymn Book, by James Evans, Norway House (present-day Manitoba), 1841. Published by the Bibliographic Society of Canada, Toronto, 1954. (OCLC 1152061)

To see a fully digitized version of the 1841 Cree Syllabic Hymn Book by James Evans, visit the University of Alberta Libraries’ Peel’s Prairie Provinces collection.

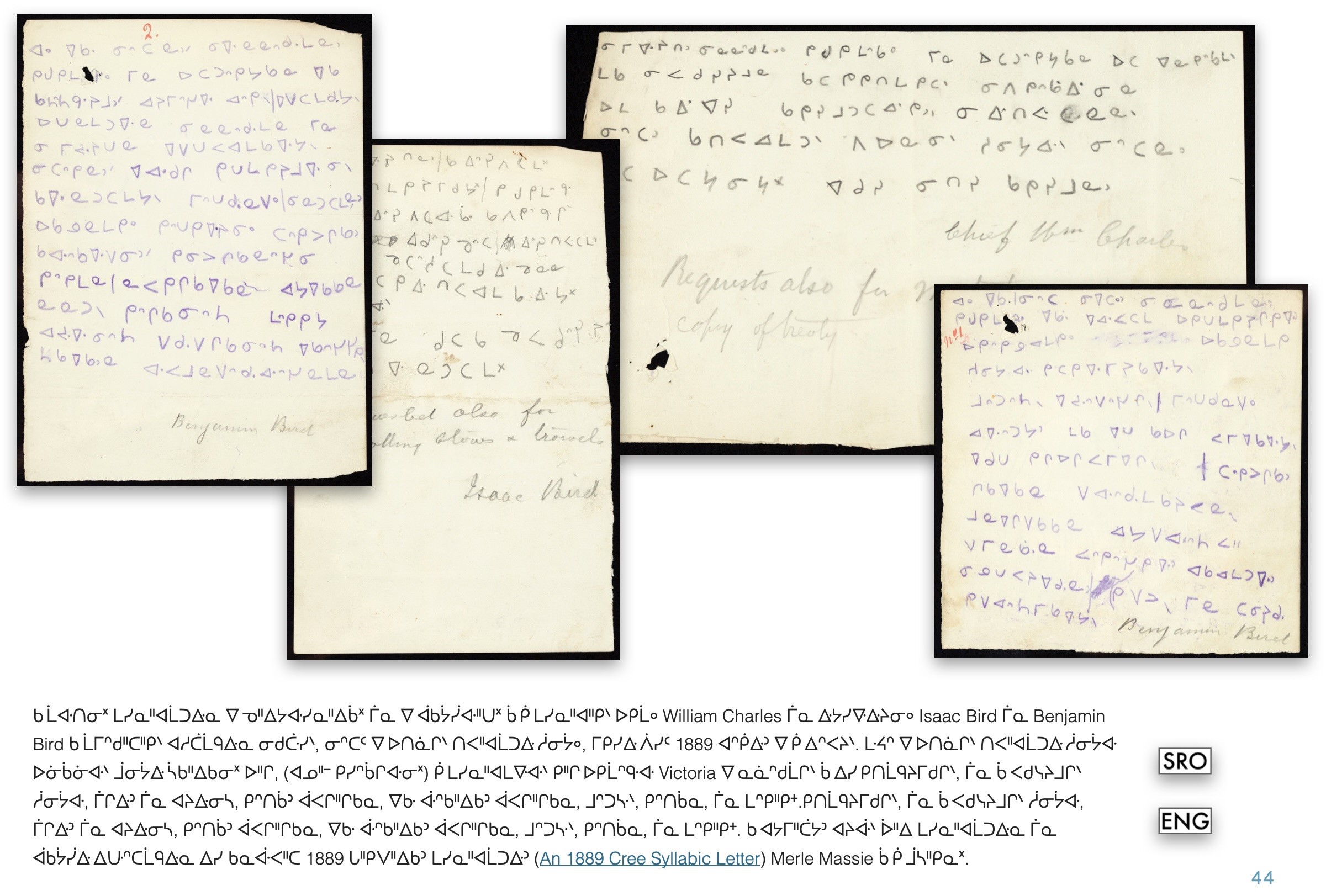

Group of letters written in Cree with some English by Chief William Charles and councillors Isaac Bird and Benjamin Bird regarding Treaty 6, February 1889. Before receiving their first treaty payment, the Cree leaders from Montreal Lake (present-day Saskatchewan) wrote to Queen Victoria asking for her compassion to their people, and their expectations that included money, food and clothing, tools and household utensils, livestock, seeds, and medicines. (MIKAN 2058802)

To read more about these letters and the English translations, see “An 1889 Cree Syllabic Letter” by Merle Massie.

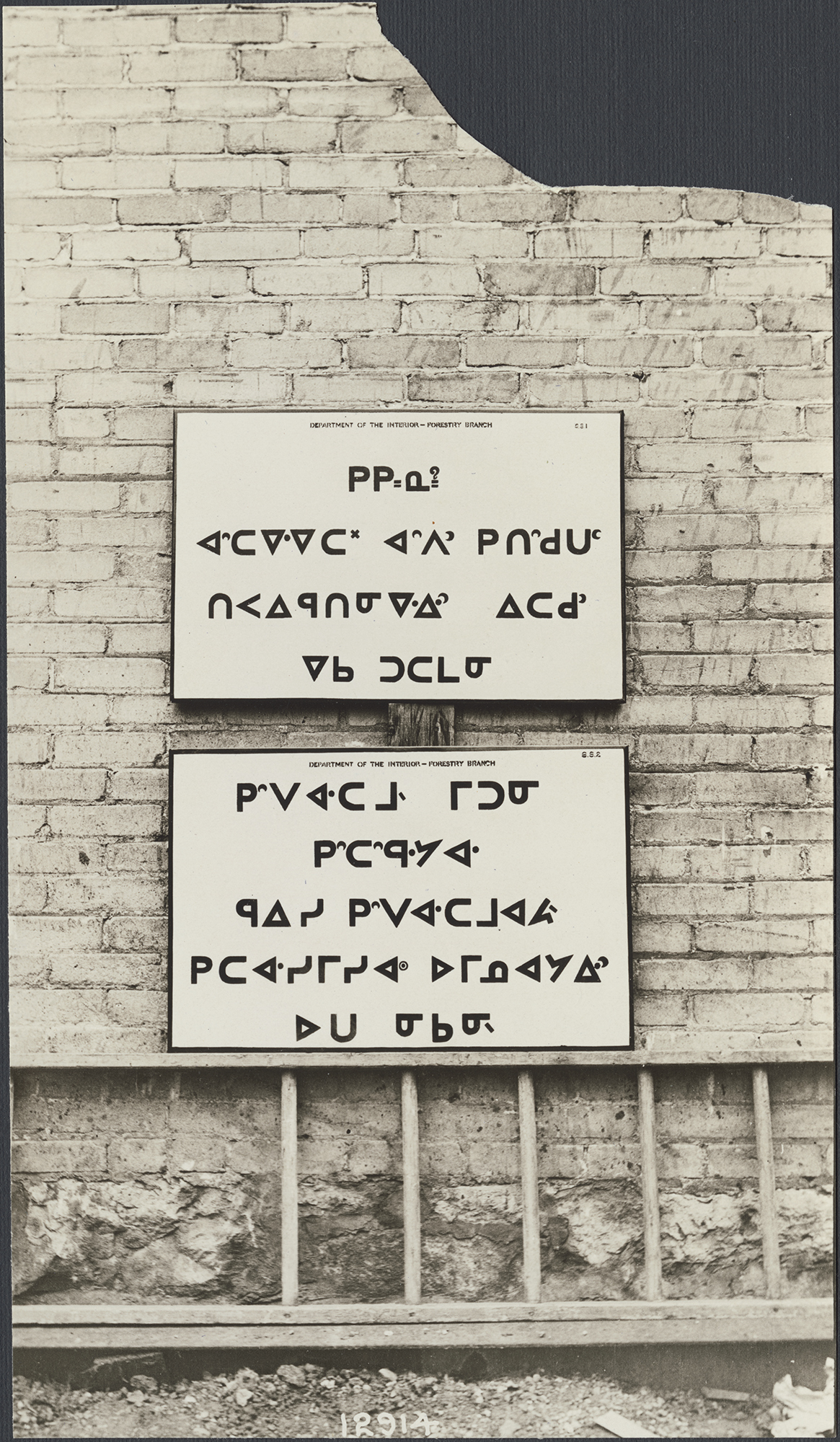

Over time, syllabics continued to increase in popularity. They were used in government offices, street signs and personal correspondence. There was even a Cree syllabics typewriter, shown in the photograph at the beginning of this essay. The typewriter was developed by Olivetti in collaboration with representatives from various Cree organizations in Western Canada and Quebec. According to the 2016 Census, nêhiyawêwin is one of the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in Canada.

Cree syllabics had not only become popular with nêhiyânâhk (Cree country), but their use also spread to other languages such as Anishinaabemowin, Inuktitut and some of the Dene languages, by adapting the syllabary to those languages (see Inuktut Publications essay in Nations to Nations: Indigenous Voices at Library and Archives Canada).

Cree Construction Company sign from Quebec, unknown location, ca. 1978–1988. Credit: George Mully. (e011218399)

Department of the Interior, Forestry Branch, sign in Cree, unknown location, unknown date. (e010752312)

Methodist Reverend James Evans as inventor of the syllabary is questionable at best. Evidence points to the fact that he was unskilled in the nêhiyawêwin, yet we are expected to believe that he created a syllabary that worked so well with nêhiyawêwin. While the theory that Evans conceived the syllabary is widely supported in mainstream history, I was unable to find anything concrete that supported this idea. The only evidence I could confirm was that he created the physical stamps for printing in syllabics. Archdeacon Horsefield, who translated the 1841 Cree hymn book, commented on Evans’s Cree abilities as follows:

“The vocabulary of the author is pretty extensive, but his syntax is poor: he uses plural nouns with singular verbs, and vice versa, is uncertain of word order and (not unnaturally) lost among some of the more complicated forms of the truly weird and wonderful Cree verb.” (2)

A researcher named Louis (Buff) Parry read Evans’s diaries and letters but could not find any evidence of how or when Evans invented “his” syllabics (3). Indeed, Christian churches had much to gain by claiming the invention of the syllabary. They could spread the word of the Bible while declaring that they had brought a great gift to nêhiyawak.

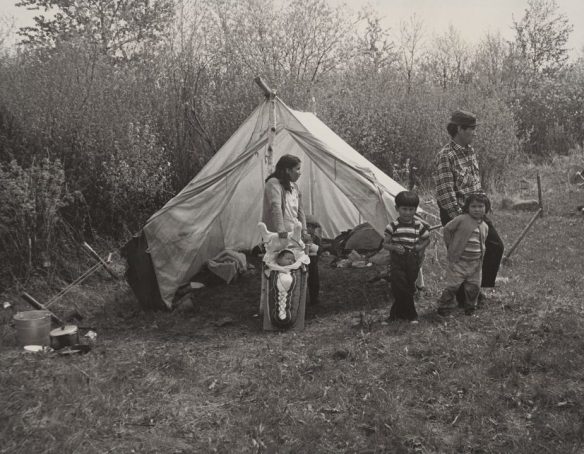

In time, Church and Crown joined forces to implement the Indian residential school system. By 1894, children aged 6 to 16 were forced to attend these schools. Part of these colonizing efforts included rules that restricted the use of Indigenous languages. Many children of these residential school survivors were deprived of their language due to the physical and emotional abuses their parents endured in the colonial school system.

nêhiyawak proved their resiliency by easily and quickly adapting to ways of writing, reading and teaching their language. We are capable and resourceful people who had ways of recording knowledge before contact. These ways may not have fit the Eurocentric models, but they existed. I have no doubt that we played a much larger role in the creation of Cree syllabics than is related in history books. It is my hope that we can continue on this path of language revitalization to undo the damage inflicted upon us by the residential school system, inaccurate historical records and colonization.

References

- Lorena Sekwan Fontaine, “Our Languages are Sacred: Finding Constitutional Space for Aboriginal Language Rights,” doctoral thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 2018, p. 62.

- James Evans, Cree Syllabic Hymn Book, Norway House, N.W.T.: [Rossville Mission Press, 1841], p. 9.

- Lesley Crossingham, “Cultural director says missionaries didn’t invent syllabics, Indians did,” Windspeaker, vol. 5, no. 42, 1987, p. 2.

Windspeaker finding aid at Library and Archives Canada

Additional Resources Related to Cree Writing and Syllabics

- CBC interactive story: A question of legacy: Cree writing and the origin of the syllabics, Wes Fineday on CBC Radio’s “Trail’s End,” March 6, 1998 and, Winona Wheeler speaks on CBC Radio about the creation story of syllabics

- Syllabics and SRO (Standard Roman Orthography): Two sides of the same coin (and Plains Cree Syllabics chart, y-dialect), Cree Literacy Network

- SRO (Woods) Cree Syllabic Chart, th-dialect, Lac La Ronge Indian Band

- Downloads for a Cree syllabics keyboard, Language Geek

- SRO to syllabics converter for Cree (n-dialect, th-dialect and y-dialect), Eddie Santos

- itwêwina: Plains Cree Dictionary, Alberta Language Technology Lab, in collaboration with the First Nations University and Maskwacîs Education Schools Commission

Samara mîkiwin Harp was an archivist with the Listen, Hear Our Voices initiative at Library and Archives Canada. She now works in Woods Cree language revitalization and is further pursuing archival studies. Samara grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, with Cree roots in both the Southend and Pelican Narrows areas of Treaty 6 in northern Saskatchewan. The first of her father’s family arrived in Ontario in the 1800s from Ireland and England.

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/image-1.jpg)

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/image-1.jpg?w=584&h=365)