This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

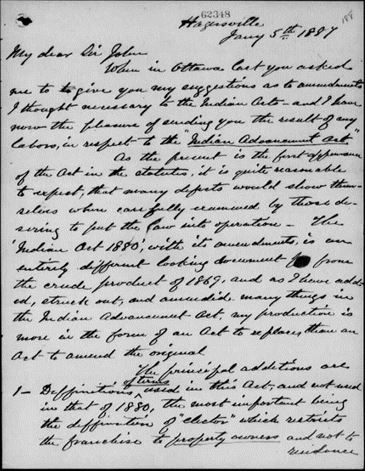

By David Horky

The records documenting the Manitoba Penitentiary’s beginnings at the “Stone Fort” (Lower Fort Garry), from 1871 to 1877, are almost as old as the province of Manitoba itself and are a testament to the turbulent origins of the new province. Many of the records from this early period of the penitentiary, such as the Inmate Admittance Books, Warden’s Order Books and Surgeon’s Daily Letters, held at the Winnipeg office of Library and Archives Canada (LAC), are also available online at Canadiana Héritage. There are also various other documents pertaining to the Manitoba Penitentiary held by LAC or other sources, many of which are accessible online. Together, these records supply details about the penitentiary and some of the inmates themselves, providing a fascinating perspective on Manitoba’s early history immediately following its creation in 1870.

The Stone Fort

Fur store, interior of Lower or Stone Fort, 1858 (e011156706); this building housed the original Manitoba Penitentiary and Asylum from 1871 to 1877

The Manitoba Penitentiary was established at Lower Fort Garry in 1871, shortly after Manitoba entered Confederation as the Dominion of Canada’s fifth province in 1870. The fort was originally built by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1830 on the western bank of the Red River, 32 kilometres north of the original Fort Garry (in present-day Winnipeg), and it served as a trading centre and supply depot for the Red River settlement.

The Stone Fort had previously been the headquarters for the British and Canadian troops under the command of Colonel Garnet J. Wolseley. This military force was sent by the Canadian government in 1870 to establish peace and maintain order following the Métis-led Red River Resistance that ushered in the creation of the province of Manitoba. Ironically, the Canadian troops, particularly those from Ontario, were widely accused of conducting a “Reign of Terror” (English only) of violence and intimidation with impunity against the Métis of the Red River settlement.

When Wolseley and the British troops vacated the fort in 1871, the Canadian troops were relocated to Upper Fort Garry and the Fort Osborne barracks. One of their number, Samuel L. Bedson, a quartermaster sergeant in the 2nd (Quebec) Battalion of Rifles, remained behind to serve as the first warden of the Manitoba Penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry.

Within the fort, the stone warehouse was converted into a prison for criminals and an asylum for people living with mental illness. Bars were added to all windows and dormers, the western doorway was blocked up, the eastern door was adapted for prison security, a signal mast and ball were added, and palisades were erected.

No ordinary prisoners: Indigenous inmates and Manitoba’s history, 1871–1877

The number of inmates listed on the admittance register for the first couple of years of the Manitoba Penitentiary’s operations was quite small, only seven. In 1871 and 1872, the crimes listed involved horse theft, petty larceny, theft, and breaking and entering. Even at this early date, the inmates had surprisingly diverse origins: a Swede, a few Americans, an Englishman, some Canadians from Ontario, and a few from the Red River settlement itself. Included in this early listing is a person identified in 1874 as a “lunatic”—a harsh term then used to describe someone living with a mental illness. The penitentiary, both here and at its later location at Stony Mountain, served as an asylum for these people until the opening of the provincial asylum in 1886 in Selkirk, Manitoba, which was the first of its kind in Western Canada.

The admittance register recorded the names, convictions and sentences of this initially small number of inmates. However, other sources provide information about the circumstances leading to their imprisonment. In the case of Indigenous prisoners from First Nations and Métis communities incarcerated at the Manitoba Penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry, the context of contemporaneous events within the Red River settlement, and more broadly the Northwest Territories, is especially important.

In fact, the very first inmate listed on the admittance register in May 1871 was John Longbones from the Dakota First Nation, sentenced to two years for “assault with intention to maim.” A few years later in 1873, two other men from his community, Pee-ma-ta-kow and Mc-ha-ha, would be sentenced to prison at Lower Fort Garry for larceny and breaking-and-entering respectively.

The small number of First Nations inmates at Lower Fort Garry at this time reflected the fact that they were being punished for breaking the law—and being caught—within an established settler community. Indeed, at the time, the broader applicability of the law of the Dominion of Canada to the outlying regions of the northwest was not recognized by First Nations peoples, nor was there then a means to enforce it.

On the question of extending the laws of the Dominion of Canada to First Nations communities, the Manitoba Penitentiary was to play a significant, if largely symbolic, role. The Canadian government sought to prepare the way for the orderly settlement of the new province of Manitoba and the recently acquired Northwest Territories. With an increasing number of newcomers arriving from Eastern Canada (particularly Ontario) and abroad, the Canadian government attached great importance to negotiating treaties with First Nations as a key element in establishing “peace, order and good government” in the Canadian West.

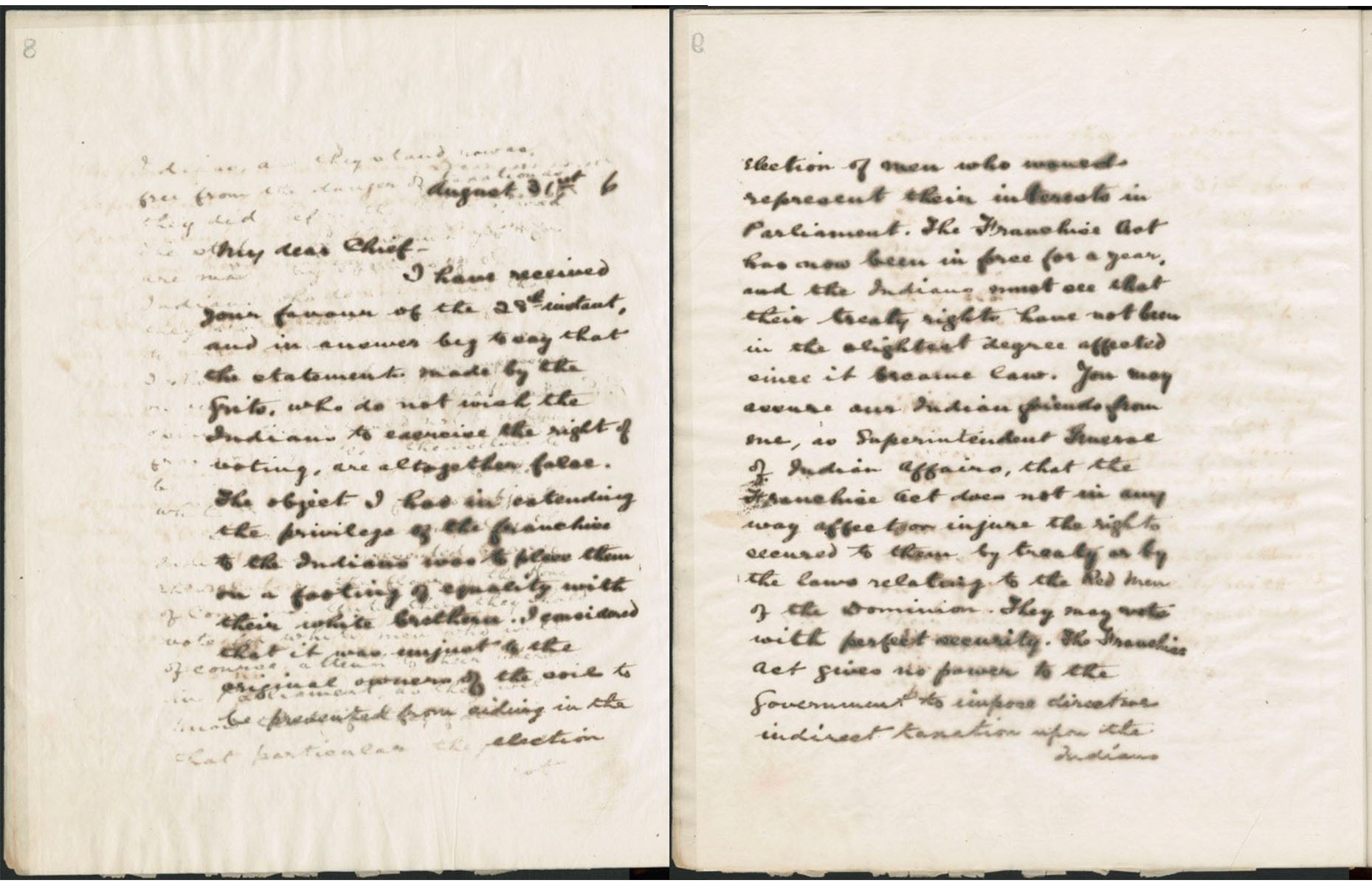

Adams G. Archibald, July 29, 1871, Report of the Indian Branch of the Department of the Secretary of State for the Provinces, 1871 (e18710014)

As fate would have it, the first of these treaties took place under the shadow of the Manitoba Penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry on July 25, 1871, as the topics of law and punishment became central issues in the negotiations. In a report by the Indian Branch dated July 29, 1871, Adams George Archibald, the first Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories, describes his meeting with the Chiefs of the Chippewa and Swampy Cree to negotiate the signing of Treaty No. 1. To his astonishment, the Chiefs were unwilling to proceed until first a “cloud was dispersed.” Archibald learned that the Chiefs were troubled by the imprisonment of a number of their brethren at the Manitoba Penitentiary for breach of contract and desertion of service with the Hudson’s Bay Company. In reply to the Chiefs’ demands for their freedom, Archibald insisted, “every offender against the law must be punished.” Nonetheless, given the importance of the treaty to the Canadian government, he assented to their release, not as a matter of law but as a “favour” extended on behalf of the Crown. Negotiations then resumed, and Treaty No. 1 was signed a few days later on August 3, 1871.

At the same time that the Canadian government was initiating treaties with First Nations, there was also growing concern with continued Métis unrest in the Red River settlement. Angered and frustrated with the Reign of Terror perpetrated by the Canadian militia and with the broken promises over the protection of their rights and land, a small number of Métis allied themselves with a group of Fenians operating across the American border at Pembina (in present-day North Dakota). The Fenians were Irish nationalists living in the United States who sought to capture Canadian territory to exchange for Irish independence from British rule.

In October 1871, a few Métis participated in the Fenian-led raid (English only) on a Hudson’s Bay Company outpost at Emerson, near the American border. Intended as a prelude to a potentially wider incursion on the entire Red River settlement, the raid was foiled by the intervention of the American cavalry from Pembina. Some captured Métis participants were later taken by Canadian officials to Winnipeg for trial for “feloniously and unlawfully levying war against Her Majesty.”

Only one of these Métis, Oiseau Letendre, is among the small number of inmates recorded on the Manitoba Penitentiary admittance register for 1871. Listed as being from Red River, Letendre actually resided across the American border at Pembina. No reason is given for his incarceration, although it clearly shows that he was given a hefty 20-year sentence. A small note subsequently added indicates that he was later released in 1873 by order of the Governor General.

Oiseau Letendre was tried before Mr. Justice Johnson in a capital case at Fort Garry, Manitoba, for levying war on Her Majesty; the sentence was commuted to [imprisonment] for 20 years, 1871–1872 (e002230571)

Records from his capital case file indicate that Letendre was a buffalo hunter and cart driver on the trails that transported goods between Fort Garry and St. Paul. Letendre had numerous family ties to the Red River settlement and the community of Batoche along the South Saskatchewan River. Consequently, Dominion officials were fearful that Letendre’s opposition to the Manitoba government was not an isolated case, so he was made an example and sentenced to hang. In an act of clemency, Letendre’s sentence was commuted to 20 years by Prime Minister John A. MacDonald. However, as Letendre claimed American citizenship, substantial diplomatic pressure was exerted by the United States government for his release. Consequently, Letendre was granted a pardon by the Governor General in January 1873 on the condition of his exile from Canada until the expiry of the 20-year sentence.

Shortly after Letendre’s release, there was another and even more high-profile case involving the arrest and trial of a prominent Métis individual who was also incarcerated at the Stone Fort, though briefly. Ambroise Lépine, Louis Riel’s adjutant in the provisional government, was arrested in September 1873 and tried for his involvement in the execution of Thomas Scott during the Red River Resistance in 1870. Ironically, both he and Riel opposed Métis involvement in Fenian plans to invade the Red River settlement. In fact, while both were still fugitives, they returned surreptitiously in October 1871 to lead volunteer troops from St. Boniface to defend the settlement against the Fenian threat.

After his capture, Lépine was initially conveyed to the Penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry for “safe keeping.” It is not clear how long he was incarcerated there, as his imprisonment was not recorded on the inmate admittance register. At some point toward the end of 1873 or the beginning of 1874, Lépine was transferred to the new provincial prison that was being built next to the courthouse in Winnipeg. This is where Lépine’s subsequent trial took place and where he later served his sentence.

Lépine’s trial was followed with intense interest not only in Manitoba, but also throughout the country. As would be the case a dozen years later with Riel’s trial in Regina, Lépine’s trial in Winnipeg also polarized the nation, provoking his condemnation in Ontario while evoking sympathy for his cause in Quebec. And like Letendre, Lépine was initially sentenced to hang. However, the Governor General eventually commuted his sentence to two years but nonetheless revoked his civic rights indefinitely. Later, Lépine was even offered a full amnesty subject to exile for five years, but he refused and served his full sentence, finally obtaining his release in October 1876.

End of an era

Many of the issues encountered during the early history of the Manitoba Penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry, reflecting the turbulent origins of the province and its uneasy relations with First Nations and Métis communities, would have wider repercussions as the Canadian government promoted settlement further westward.

By 1877, the Canadian government had negotiated most of the numbered treaties 1 through 7 with First Nations, covering vast portions of the Northwest Territories in present-day Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. This paved the way for the development of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the advancement of colonial settlement across the Prairies. Conversely, as settlement progressed, the situation of many First Nations became more desperate as their traditional means of securing food supplies were increasingly compromised or—in the case of the bison hunt—had suffered irreversible collapse.

The Métis communities of the Red River settlement were also reeling under the pressure of more settlers pouring into Manitoba from Eastern Canada and abroad. Despite the assurances made in the Manitoba Act, the Métis had suffered from the Reign of Terror conducted by the Canadian Militia and from land swindles perpetrated in the law courts. Consequently, thousands of Red River Métis left Manitoba in the 1870s in a westward diaspora, either joining pre-existing or establishing new Métis communities in present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Perhaps in anticipation of encountering increased trouble in Manitoba and the Northwest Territories from the desperate and dispossessed, the Canadian government took steps to extend the long arm of Canadian law in the northwest. Territorial courts were established for prosecution, and the North West Mounted Police was created for enforcement. Moreover, preparations were being made as early as 1872 to replace the Stone Fort at Lower Fort Garry with a new and larger federal penitentiary to serve as the site of punishment for the entire region.

Thus, the era of the Manitoba Penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry ended with the completion of the new Manitoba Penitentiary at Stony Mountain in 1878. By this time, Manitoba was also entering a new era in the nation’s history, assuming its role as the “keystone province,” the administrative and logistical centre for all of Western Canada.

The Winnipeg office of Library and Archives Canada also has many of the records of the Manitoba Penitentiary at Stony Mountain (or Stony Mountain Penitentiary, as it was later called), available online at Canadiana Héritage, but they are deserving of many more, equally fascinating, stories.

David Horky is a senior archivist in the Winnipeg office of Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg)