By Ellen Bond

Photos surround us every day. Whether its framed photos hanging on a wall, advertisements seen as you drive by, or folks taking selfies, images are everywhere. In honour of World Photography Day, I want to share how much photography means to me and how it has shaped my world.

Photography brings me joy. I remember my parents’ Polaroid camera and the excitement of seeing the photo magically appear after it slid out of the camera and the air exposed the image. Though the quality wasn’t as great compared to a film camera, the instant gratification was like today’s cell phone cameras—you could see what you captured right away.

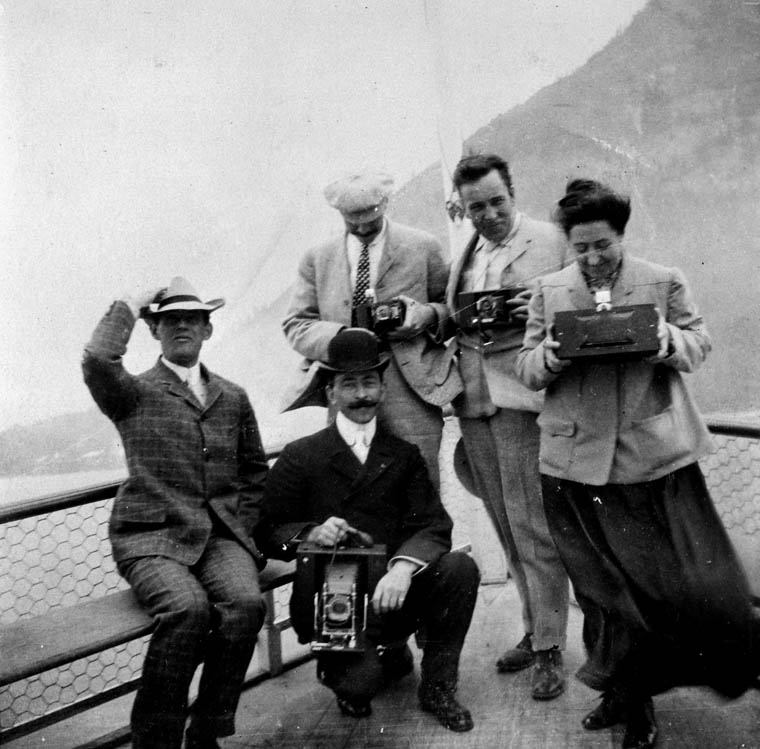

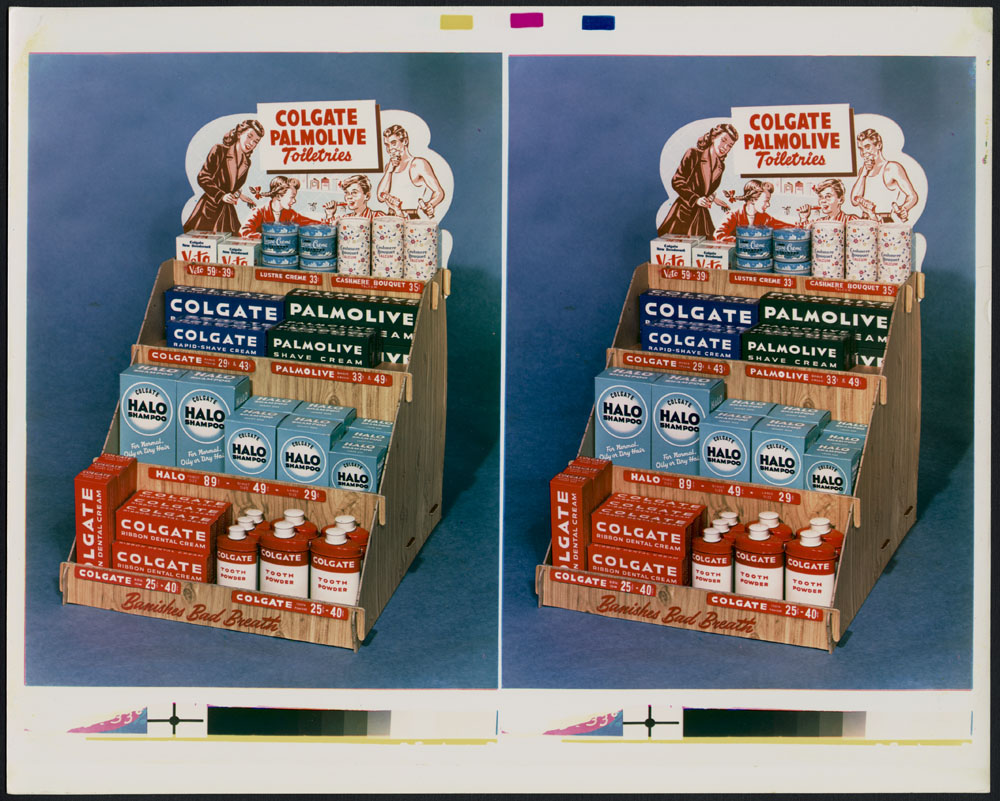

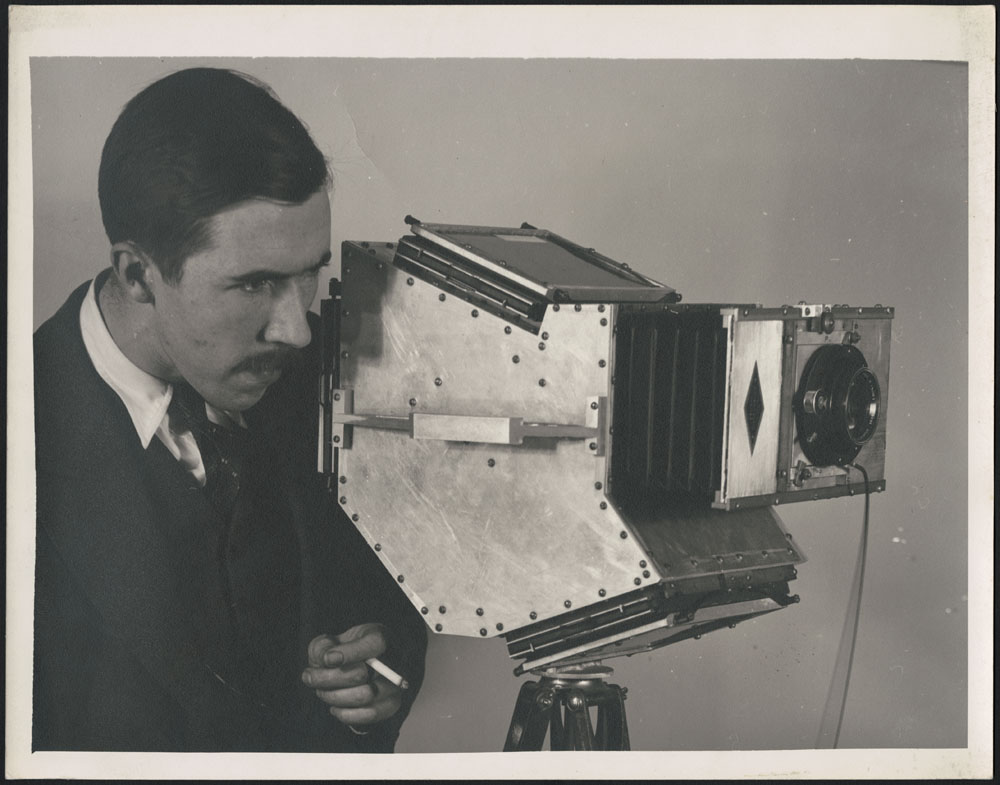

People showing various types of cameras, 1904. (a148285)

While finishing my photography diploma, I began taking pics for a community newspaper in Ottawa. This had me visiting local stores and events and interviewing and photographing locals for a regular feature. The summer between my first and second year, I shot thousands of photos in and around Ottawa. At the end of my last semester, our class took a field trip to Library and Archives Canada’s (LAC) Preservation Centre in Gatineau, and I knew I wanted to work there.

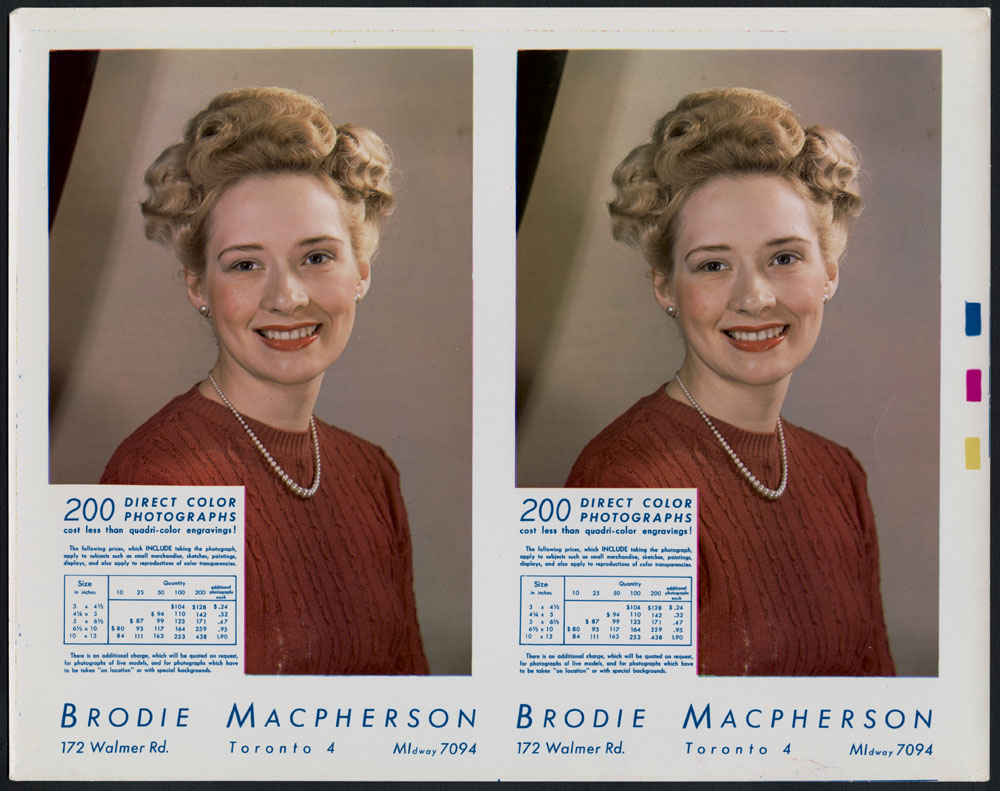

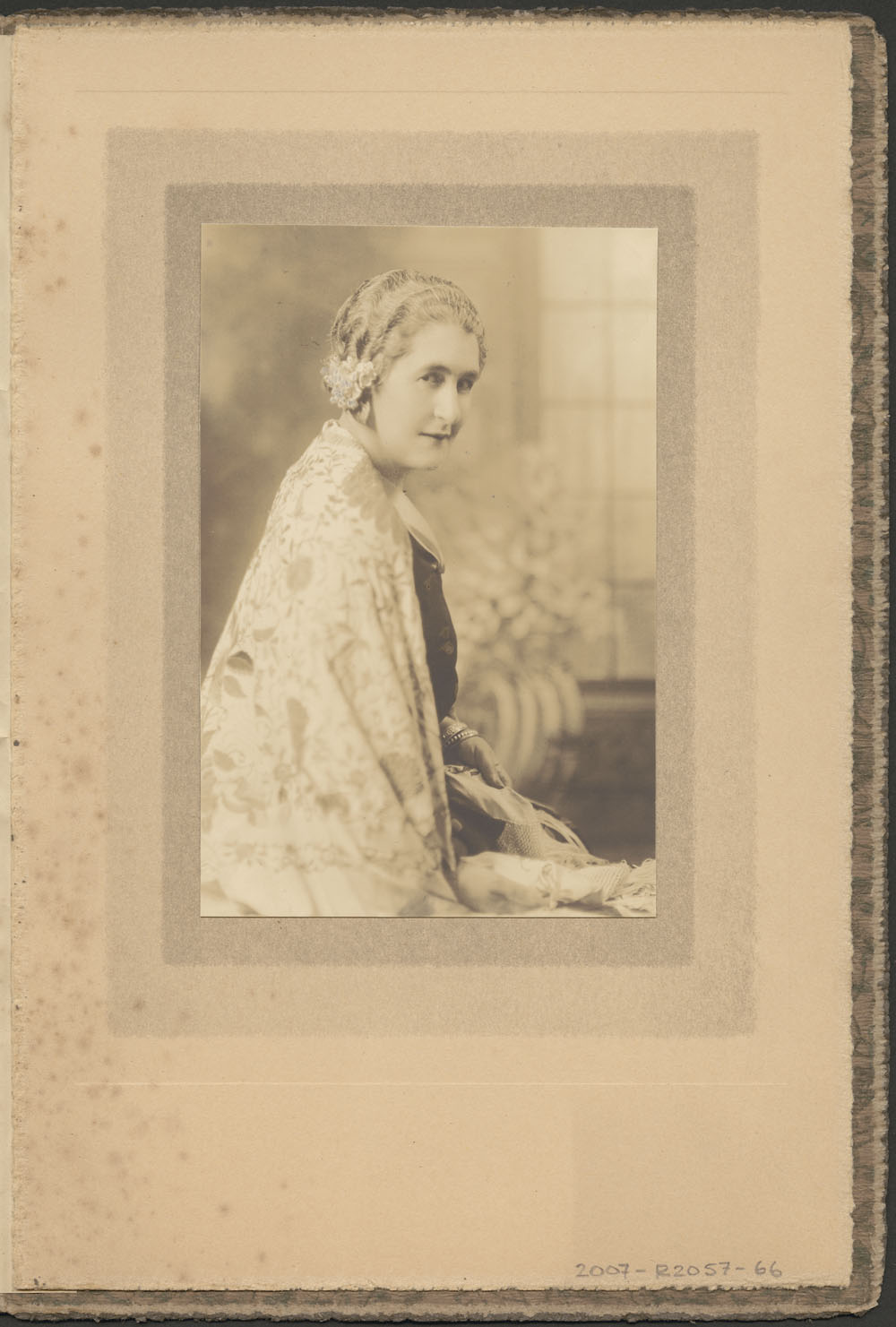

Photographer Rosemary Gilliat Eaton holding a twin-lens camera. LAC holds many of Gilliat’s photos in its collection. Credit: Rosemary Gilliat Eaton. (e010950230)

In the summer of 2016, after graduating, my vision came true. I began working on LAC’s Canadian Expeditionary Force digitization project, during which time I helped digitize over 622,000 files relating to Canadians who served in the First World War. You can now search for those files by name using LAC’s Personnel Records of the First World War database. I used my skills to digitize a variety of files, maps, certificates, X-rays, pay forms, medical forms, attestation papers, personal correspondence, and too many files labelled “missing in action” or “killed in action.” I gradually learned more and more about LAC and applied for a job with their Online Content team.

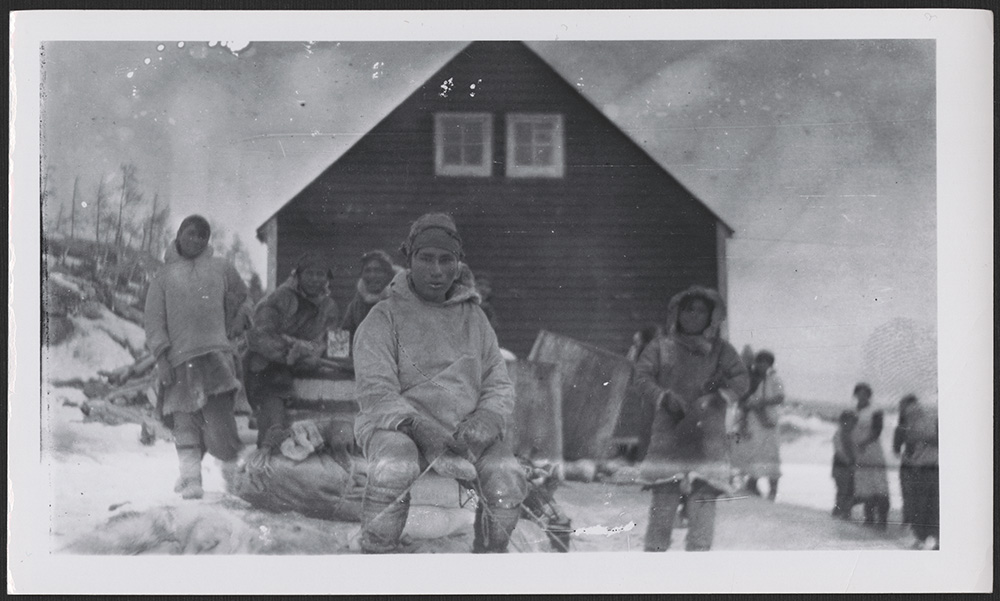

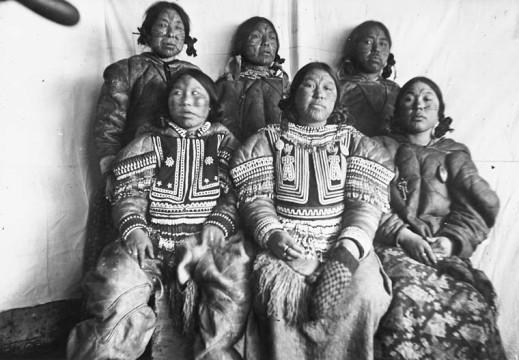

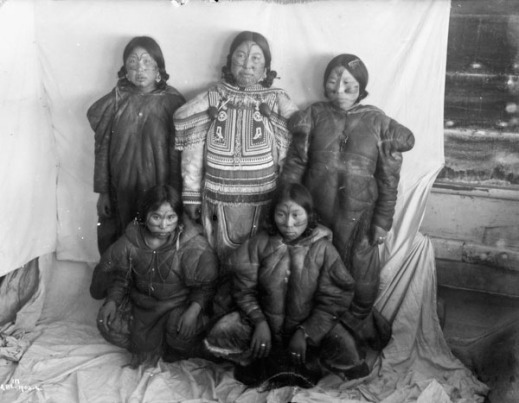

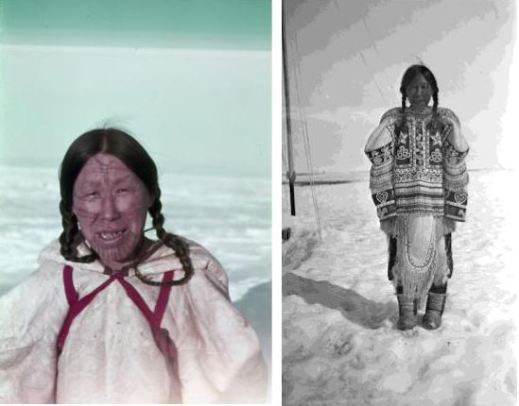

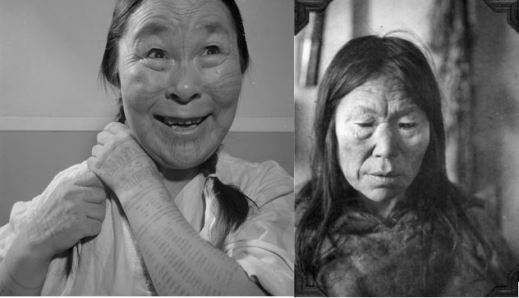

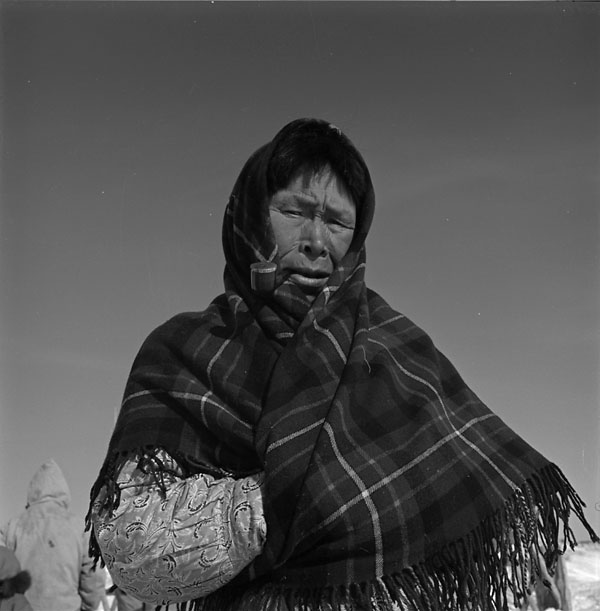

When I started working with the Online Content team, I contributed to blog posts, the podcast, and finding photos for Flickr albums. I also began working on Project Naming and eventually became the project manager of this endeavour, which is rooted in sharing historical photographs of First Nation, Inuit and Metis Nation people whose names were not recorded when their photos were captured.

A Haida woman holding up a Japanese glass net float, Skidegate, Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, ca. 1959. Thanks to Project Naming, the person in this photo was identified as Flossie Yelatzie, from Masset. Credit: Richard Harrington. (e011307893)

Participation in Project Naming helps improve the narrative of photographic records held at LAC. Photos are posted three times a week on Project Naming’s social media pages. When names or information are received, the records are updated, which helps preserve and honour the people in the photos for generations to come. As a way of saying thank you, we offer a high-resolution print of the photo at no charge to the people who shared the information. The best part of my job is adding someone’s name to the record database. That name becomes attached to the record, making it searchable forever.

Outside of LAC, I continue to hone my photography skills by working for local college athletic teams and theatres, a local newspaper, other athletic teams, and various Ottawa events. This past year, I photographed the Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL) for The Hockey News. This led to an opportunity to take photographs at the 2024 International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) Women’s World Championships, where Canada defeated the United States in the gold medal game. I hope to someday donate my hockey photos to LAC to document the first year of the PWHL, Canada’s gold-medal win, and this major step in women’s hockey.

The moment after Canada defeated the United States for the gold medal at the 2024 IIHF Women’s World Hockey Championship. Photographer: Ellen Bond.

I look forward to the future with my camera in hand!

Ellen Bond is a Project Manager with the Online Content team at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=519)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg)

![Six small sketches of different types of icebergs in pale colours with the caption: “Vanille, fraise, framboise – boum, servez froid!” [Vanilla, strawberry, raspberry—boom, serve cold!]](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/e008444012.jpg)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)